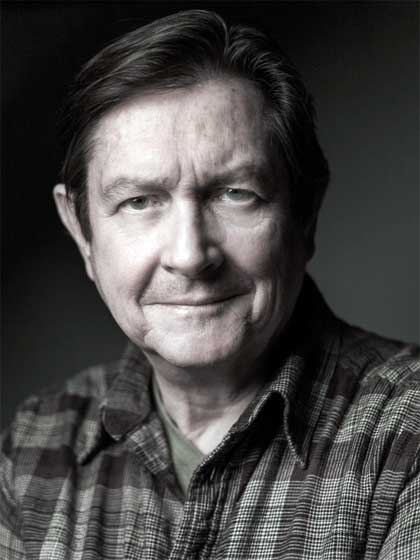

Interview

Tim Jackson

Director of the new film

When Things Go Wrong: Robin Lane’s Story

Tim Jackson’s new film about Robin Lane is having a premiere benefit screening at the Regent Theatre in Arlington, MA, on Friday, April 4, 2014 at 7pm. For more details about the event, please check out this notice on Boston Arts Diary.

Tim Jackson, long time Somerville-based filmmaker, is amazingly diversified and energetic. Not only is he producing and directing a new film, his third documentary, but he is, as well, a professor at a local arts college, a film reviewer for the Boston-based online magazine ArtsFuse, an active musician (as drummer in The Band That Time Forgot), a drum teacher, an actor, and, no doubt, some number of other things I am forgetting to mention or which I have not heard about yet. He is also accessible, passionately articulate, and full of interesting stories. We spoke for over an hour, and I have consolidated and reproduced some of that conversation here.

BAD: Tell me about your film project with Robin Lane.

TJ: I toured as a drummer for about four years with Robin Lane and the Chartbusters in the late 70s and early 80s, and I’ve known her for 35 years. And I wanted to tell a good story.

I had made two films, the first one about the American Repertory Theatre, in the early 2000s, just after Robert Brustein left, during the Woodruff era, before Diane Paulus. It’s a little out of date now, but I had the chance to interview all kinds of interesting people: Brustein, Peter Sellars, Arliss Howard. It’s called Chaos and Order, Making American Theatre (2005), and it was focused around Andre Serban’s production of Pericles. It was my first documentary and I learned something fundamental about making documentaries: that you need to do enormous preparation first, that you become so involved that you will live with your subject until you die, and that, in the process, you will learn an awful lot. Cherry Jones (who was a repertory member of the ART in the early 80s before she went on to a major Broadway career) did the narration – an incredibly nice and agreeable person with whom to work.

radicaljesters.com

My second documentary film, Radical Jesters (2008), was about radical street artists, from pranksters and media hoaxers, of a sort along the lines of The Yes Men. One of the characters who inspired and interested me – but who I did not actually wind up profiling in the film because his story was so extensive it seemed he would almost need a film to himself – was a guy named Joey Skaggs, a great media hoaxer, who did a hoax about a Chinese restaurant serving dog meat. He also did a gag as a priest on a bicycle, going around giving confessions from it. We then heard about a parade on April 1st he organized and we were going to go, but then that turned out to be a hoax too. I found Alan Abel, who made the film Abel Raises Cain (2005). He was from my hometown (Westport, CT) and also a really good drummer. Ron English, who had done a movie called Popaganda, also figures in. The film goes from pranksters like this through The Living Theatre and The Bread and Puppet Theater, with a final interview with (Bread and Puppet founder and director) Peter Schuman. There were eleven profiles in all. I was so appalled at the time by George W. Bush, I just wanted to give my students a sense of what it meant to misbehave. In the end, the film didn’t cost me anything – I got help with editing and other things from my students. (FYI: you can stream it for free on www.radicaljesters.com, and/or you can buy a DVD.)

BAD: What was it particularly about Robin Lane that intrigued you?

TJ: I wanted to do something about artists who get older and the challenge of maintaining and sustaining a career. I also wanted to do something about musicians, and I wanted to do a feminist piece. Robin was a great musician. She had grown up in Los Angeles – her father was actually Dean Martin’s piano player. She sang as a backup singer on Neil Young’s first album, and she made a kind of splash in LA when she was young. She moved to Boston in the late 1970s and also made a splash here. She was both very beautiful and very talented.

BAD: You knew her?

TJ: I knew her socially from the Boston music scene. My wife was speaking with her at a party at one point and Robin said she was looking for a drummer for a new band she was forming. She already had signed some guitar players who had been with Jonathan Richman and the Modern Lovers, and my wife casually said talk to my husband. I was touring with a really good band at the time, but what was great about Robin was that she was very consciously putting together a group of musicians who could play better than anyone. She wanted to work in the punk scene, where the music was rougher and more raw, and where there were also a lot of amateurish musicians. She said she wanted to “obliterate melody” but do so with a great band.

BAD: You then became a part of Robin Lane and the Chartbusters …

TJ: We toured for about four years. Then, finally, when we came off the road, I got interested in video. By that point, I just needed to do something else. I also studied acting, I finished college, my wife and I had children, we bought a house, and generally I went through a lot of changes. Through all of that – and what came before and what came after – I have been very fortunate to have been married to the same person for 45 years which has for me been an incredibly stabilizing influence.

BAD: Robin Lane is still around Boston?

TJ: Yes. She had been trying to write a book about all the stories in her life, but she could never bring that to fruition. She began to give house concerts and tell stories there and that was going pretty well and I thought, how about making a movie and getting it all out there? So I sat her down in a studio and began to record her telling these stories.

BAD: Did you structure this into a documentary script beforehand or did you build it as you went along?

TJ: It was really a collage. There was a phone interview she did with a radio station and I used some of that. I went to California with her and we did an interview on Malibu Beach. It was really a treasure hunt. Eventually, there was so much material, I had to take out a lot. For example, it turns out Robin was sitting with Steve Stills when he wrote the song For What It’s Worth for Buffalo Springfield that begins There is something happening here, what it is ain’t exactly clear… but we left the story about that out because it wasn’t really part of the main theme. I left mostly what was significant about being a woman in the music business, and about all the abuse that women would have to go through in it. She has been really forthcoming during the whole process, which has truly helped to make it a treasure hunt.

BAD: She was involved in the punk scene..

TJ: Our band used to open for The Ramones so it was in that world, and she thought of herself as a punk singer for awhile, but it was in some way kind of a pose. More importantly, she always wrote great songs – she has a really great gift for it. In the film, I wanted to explore what that kind of talent is about.

BAD: What then makes Robin Lane’s story distinctive? Is it emblematic of a particular moment in rock and roll?

TJ: Her story is less emblematic than Forrest Gumpish. She wound up in certain places at certain times attempting to make music and not a lot of women did that in the rock and roll scene in the way she did. In some way, she was pioneering the role of women in rock and roll. You can go back at look at a band like Fanny – they were an early girl band, but not as talented as Robin. And Patti Smith, who was also in that scene, was mostly a poet not a musician.

BAD: How about Joni Mitchell?

TJ: She was a folksinger – there were a lot of women folksingers – Joan Baez, Janis Ian, there were a million of them. But, even as late as the late 1970s there were not a lot of women fronting rock bands. You might want to say Joan Jett – but that’s later. Or Suzi Quatro – she did that and she’s wonderful, but she’s more show business – she was even on the TV show Happy Days. But Robin was a singer-songwriter who put together an all male rock band to compete in the rock business. And I think one of the reasons we got signed with a record company is that they already had Pat Benatar, Chrissie Hynde from the Pretenders and the record company wanted one other person of the same general type, and that turned out to be Robin. Chrissie Hynde was great – a real tough ass girl in leather – that’s how you have to do it. But Robin’s image was not as strong. MTV was coming in and it turned out they needed someone with a stronger image. And, as time went on, it became less clear to the record companies what it was they were trying to sell with Robin.

BAD: Did she have a particular calling in all of this? She started as a folksinger and then morphed into a punk singer – was that just to go with the flow, to build an image to sell?

TJ: I think she did take that on. She liked the energy of the punk rock scene and wanted to morph onto it. But there was also another significant factor that played into things – she was a born again Christian, from way back, though none of the rest of us in the band were.

BAD: How did that affect things?

TJ: If you listen to the lyrics, they’re all written authentically with a higher purpose in mind, not so you’d necessarily notice – it’s written without proselytizing – but you can find it now if you look for it. Maybe that factor also didn’t help so much with the image the record company was looking for.

(back in the day)

Photo: Christian New Wave

BAD: Did she remain a born again Christian?

TJ: Now I’ll be speaking for her, imagining what she might say. I’d say she’s distressed by the current state of religion, so that has rocked her faith to some extent, but it’s still in her heart. It was an authentic thing that she needed at that point in her life, but which she doesn’t talk about much now.

BAD: It seems like such an interesting combination – punk rock and born-again Christianity. Are there any other examples of musicians into those two things?

TJ: There are heavy metal Christians.

BAD: But punk is a little more iconoclastic. Heavy metal is loud and Dionysian, but punk is…

TJ: … tip over the barriers. Yeah, there’s a cry for help in there somewhere. These are all things I look for in the movie. So, she says at one point I was looking for the father I never had. What fascinates me about Robin is her ability to hang in there. Now she does songwriting workshops with female survivors of trauma, after having gone through a certain amount of traumatic events in her own life. The issue of how people maintain their lives is fascinating to me. How Robin has changed to maintain hers is really central to the film, so it starts with one of these workshops.

BAD: Were there any big surprises, any revelations, any ahas about the story that emerged?

TJ: Yeah, huge. During the making of the movie my wife convinced Robin to go look for the child she gave up for adoption in 1969. In the movie she sings the song Benjamin, which she named for that child and which in many ways represented the fertile beginning of her songwriting career.

BAD: Did they ever meet?

TJ: And how, with my camera running. But we don’t include the actual footage in the movie because there were some family concerns about that. He’s a great guy, and, to boot, he’s in the music business. There is also footage of Robin’s daughter, who says at one point “I sometimes worry that Mom lost the record contract because of me, but she loves me SO much…”

BAD: Was that giving up of her child the trauma she was recovering from?

TJ: There were other things as well, some of which are mentioned in the film.

BAD: What is the rollout plan for the film? You have the screening at The Regent in April, then what’s next?

TJ: A lot of people knew I was working on this and wanted to see what it was. So I arranged the screening to get the audience’s initial reaction. Also, if I am going to distribute the film more widely I have to figure out about paying for the rights to use the songs, among other things, and I’ll need a bit more funding to handle that before this film can really see the light of day.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply