Play (1994)

by Yasmina Reza

Translated by Christopher Hampton

Directed by Antonio Ocampo-Guzman

New Repertory Theatre

Arsenal Center for the Arts

Watertown, MA

January 15 – February 5, 2012

With Robert Walsh (Serge), Doug Lockwood (Yvan), Robert Pemberton (Marc)

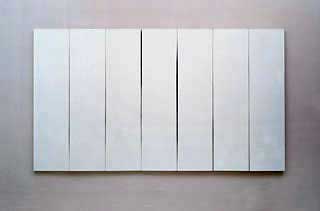

White Painting (seven panel), 1951. Oil on canvas.

Three middle-aged Parisian friends converge and joust around a recent acquisition. Serge has just bought an almost all-white painting for a great deal of money. His opinionated friend, Marc, takes him to task for doing so, calling it “white shit.” Yvan, not given to opining at all, is caught in the middle. To boot, Yvan is confronting a host of complications attending his forthcoming first marriage, making him endlessly anxious. The tension over the painting, and all that it evokes, builds, until the finale, when dramatic gestures open new paths.

Robert Pemberton (Marc)

Photo by Andrew Brilliant/ Brilliant Pictures.

This concise, but wonderfully written, play reveals new gems each time I read it or see it performed. I have read it many times – I used to teach it in an aesthetics class every semester – and this is the third time I have seen it staged.

On the one hand, the play is about a triviality – a difference of taste about minimalism – and how near cataclysm erupts from this seeming insignificance. (God of Carnage, in production at the Huntington Theatre, and in its recent film version as Carnage, also demonstrate Reza’s capacity to dramatically transform bumps into mountains.)

On the other hand, Art is about the interpretation of minimalist works, and about how the complex lines of life inevitably map onto their nearly bare canvases. In its brief, tragicomic lyricism, the play poses its own poignantly ironic alternatives.

This production is really wonderful and adds new subtleties to what I have encountered before.

There is something marvelously lyrical about the deliveries in this rendition. In past productions, I was aware of dialogue conveyed dominantly with staccato punctuation and great urgency; in this one, I sensed a kind of lilting ease.

Yvan has a great, very long soliloquy after his entrance. I have heard it delivered breathlessly and urgently in other productions, which, by its sheer velocity, contributes to a kind of frenetic humor.

Here, Doug Lockwood offers the soliloquy in a wonderfully nuanced and paced fashion, enabling one to sequentially digest the logic of its dilemmas and complaints. It is still funny, but in a quieter, and more satisfying, though no less desperate, way.

Because of Lockwood’s adeptness in conveying Yvan’s singular awareness of his neurotic vulnerabilities at the same time he exhibits the agitation that results from them, Yvan carries a penetrating tenderness rather than something more bluntly pathetic.

Photo by Andrew Brilliant/ Brilliant Pictures.

Robert Pemberton’s Marc begins the show with the dilemma of confronting his friend’s acquisition of the nearly all-white painting. It begins: My friend Serge has just bought a painting. It’s a canvas about five foot by four: white.

Pemberton gives the delivery with a stolid but believably assured stance. His Marc is not just a stick in the mud (as Marc can easily be interpreted), but, more sympathetic, as someone conscientiously committed to his aesthetic judgments. Pemberton’s deft pacing in the delivery of the lines highlights this sense of him as a careful, rather than a vainly rigid, exponent of his position.

The play ends with a recapitulation, by Marc, of the introductory line: My friend Serge, who’s one of my oldest friends, has bought a painting…

For some odd reason, I find this recapitulation, after the play has gone through all its misdirections, very moving. And here, Pemberton, in his solidly believable way, gives gravity, heft and feeling to its cadence.

Robert Walsh’s Serge offers a kind of intoxicated giggle when, at the outset, he shows the painting to Yvan for the first time. There is something just right about this – as a giddy intellectual adventure with the vertigo it entails.

And, from that dizzying height, Walsh adeptly communicates an ambiguous stance between the honest appreciation of the work and an enthrallment with traits of lesser elevation, like the fame of the artist. Is it that the noted Antrios painted it or is there something innately in the form that appeals to Serge?

The challenge of the role is to convey that hypoxic uncertainty as Serge ejects himself into a new aesthetic atmosphere; Walsh does the job very well.

I have seen Robert Walsh in many productions of the Actors’ Shakespeare Project and he frequently conveys an assured grace in a range of roles. Here, he conveys the aura of an honestly assured aesthete, while, deftly, at the same time, calling the authenticity of that assurance into question.

Apparently, the director, Antonio Ocampo-Guzman, is not a native English speaker. In such a wordy play as this, that might be regarded as a drawback. But here it appears to have offered an opportunity to draw out the dialogue in a way that ensures its comprehensibility and impact, yielding a gracefully nuanced result.

At various points, piano solo passages were played alongside soliloquys, almost as an indicator that this were reflection rather than action. For the most part, I found them to be distractions rather than enhancements. Though they did not drive me crazy, I could have done without them, and just listened to the words which were all delivered so well they had their own resonance.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply