By George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin

Adapted by Suzan-Lori Parks and Diedre L. Murray

Directed by Diane Paulus

Choreography by Ronald K. Brown

American Repertory Theatre

Cambridge, MA

Scenic Design: Riccardo Hernandez, Costume Design: ESosa, Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind, Sound Design: ACME Sound Partners,

Orchestrations: William David Brohn & Christopher Jahnke, Music Supervisor: David Loud

Conductor: Sheilah Walker, Associate Conductor: Brian Hertz

Associate Director/Production Stage Manager: Nancy Harrington

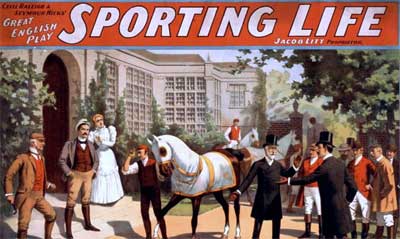

With Audra McDonald (Bess), Norm Lewis (Porgy), David Alan Grier (Sporting Life), Joshua Henry (Jake), Phillip Boykin (Crown), NaTasha Yvette Williams (Mariah), Nikki Renée Daniels (Clara), Bryonha Marie Parham (Serena), Cedric Neal (Frazier, the Crab Man), J.D. Webster (Mingo, the Undertaker), Nathaniel Stampley (Robbins), Phumzile Sojola (Peter, The Honey Man), Heather Hill (Lily), Andrea Jones-Sojola (Strawberry Woman), Wilkie Ferguson (Fisherman), Trevon Davis (Fisherman), Roosevelt André Credit (Fisherman), Alicia Hall Moran (Woman of Catfish Row), Allison Blackwell (Woman of Catfish Row), Lisa Nicole Wilkerson (Woman of Catfish Row), Joseph Dellger (Policeman), Christopher Innvar (Detective)

Photo by Michael J. Lutch, courtesy of the American Repertory Theatre

According to the advance press quoting mostly Diane Paulus and Suzan-Lori Parks, the original was to be redrawn and re-conceived quite significantly to strip away outmoded parts and bring aspects of the characters into more vivid relief. The changes, in fact, are more minor than one might think from some of the dramatic reports in the press.

An altered ending, apparently tried out in previews, was not used for the opening, and the new touches seem to work fine and do not modify the original too much.

But, we can only wonder, along with Stephen Sondheim who raised the question publicly: why use that strangely modified title?

Catfish Row, South Carolina, is a small place, basic, down and out, but rich with community life. Bess, lavishly beautiful but with scarred face (at least in this production), shows up in town with her boyfriend, Crown. Adorned and behaving like a woman of the night, she does not fit with the intimate culture of Catfish Row. Crown, a bully by nature, immediately gets into a knife fight over a craps game and kills his opponent. He flees, and Bess, remaining, rejected by all the rest of the Catfish-ites, is taken in by Porgy, a cripple. An odd match of tarnished beauty and virginal vulnerability, they nevertheless become lovers, though trouble lurks at every corner. The threat of the brutal Crown hovers, and a speedy ne’er do well named Sporting Life tries, with his magic white dust in tow, to lure Bess away to the fast life in New York. Crown eventually re-emerges, and a fight results in unexpected conquest for the underdog. Yet, difficulties for hero and heroine lie in store. At least in the ending I saw, heroine, lured by heroin, hits the road. And hero, seeking heroine, follows after.

Written in 1935, premiered in Boston at the Colonial Theatre, Porgy and Bess was a four hour marathon with a basic plot like the above, but with lots of extra detail thrown in. Even though the opening night in Boston was a great success and received a rousing response from the audience, George Gershwin famously walked around the Boston Common with his co-producers until the wee hours of the following morning trying to figure out how they could cut the show. They did, and the result which went to Broadway was shorter, though the run of it turned out was shorter, as well, than they all had expected.

Nonetheless, Porgy and Bess became a classic, receiving a variety of productions on Broadway and in operatic contexts over the succeeding years. But its fortunes on the Great White Way and its outposts have been mixed. Most recently, in 2006, having just had the experience of producing it as an opera at the Glyndebourne Festival, Trevor Nunn tried to revive it as a musical in London, but it was received poorly.

Diane Paulus, the new, young, daring, and some would say, brash, artistic director of the American Repertory Theatre got inspired to revive Porgy and Bess as a production worthy of Broadway endurance. She enlisted the great African American playwright, Suzan-Lori Parks, to help her rewrite the book and libretto to make it more contemporary and coherent, and Diedre L. Murray to do something to the music to make it work better as a Broadway style production.

There has been a lot of hype, publicity and some controversy over all of this redoing. Recently, Stephen Sondheim, who many would agree is the greatest living author-librettist-composer of musicals, wrote a long, wry and interesting letter to The New York Times reflecting on the nature of the project. In it, he criticizes its creators for their expressed attitudes about the original work and the nature of their contributions to it.

Sondheim offered pointed criticisms of comments by Paulus and Parks which he felt betrayed their lack of understanding (much less appreciation) of the original. And he offered a strong opinion about the expanded title which newly prefixes The Gershwins’ to Porgy and Bess.

I certainly agree with Sondheim that the modification of the title represents a very odd choice by the production team. If one were to produce a bold adaptation of Hamlet, would one take great pains to call the altered version William Shakespeare’s Hamlet?

Apparently, the producers did receive the impratur of representatives of the Gershwin family to take bold steps in this revival. In another sense, then, the Gershwins to whom the possessive in The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess refers might be the living Gershwins as well as George and Ira.

Photo courtesy of the American Repertory Theatre

Perhaps, as well, the producers see the adaptations as minor enough to justify reassuring the public that this still is the work of the original authors. That being said, as Sondheim appropriately points out, the refashioned title leaves out Dubose and Dorothy Heyward’s names which makes the modification not only weird but misleading.

Moreover, it is very strange to make a big deal about how much one is re-visioning and reshaping a work and then to take pains to rename it with its original authorship.

Perhaps all of this is meant to be a semiological ploy that twists us into talking so much about its oddity that word of mouth marketing automatically gets done.

Whatever all of this amounts to, the production itself is actually very good.

Audra McDonald (Bess) has a magnetic stage presence and it is hard to take one’s eyes off her. McDonald insisted on wearing a large, disfiguring scar on her face to indicate Bess’ violent past; it diminishes her magnetism not one iota.

McDonald has a big operatic voice which is resonant and hearty. But, especially in the first act when she began to sing it was so different in timbre and tone from most of the other voices that it stuck out strangely. As the show progressed, her voice seemed to blend in better. It was not clear exactly how that happened, but when it did the result as a whole was more satisfying.

Norm Lewis (Porgy) is equally attractive and charming in his own way. In this production, one of the big changes is that Porgy is a walking cripple and does not ride on the “goat cart” of the original. Lewis does a convincing job of this. He’s also a dashingly handsome middle-aged man, offering an additionally interesting take. This casting called to mind the the Propeller (theatre company) depiction of Richard III at the Huntington Theatre last spring in which the khng was cast as a poised regal with a spinal defect, not as a completely disfigured hunchback.

The show has clearly been shortened and packaged somewhat for Broadway, but, frankly, I don’t see as much revision as the general hype would have led me to believe.

The set by Riccardo Hernandez is abstract and simple, removing the shantytown details of Catfish Row associated with more traditional stagings. This simplification struck me as a good idea. It reminded me of the elegant ways in which The Metropolitan Opera has modernized sets in recent new productions of traditional operas (Don Carlo, for example). If tastefully done, it removes the baroque and the kitschy and encourages one to experience the production more vividly. Here, the set, simply but elegantly conceived, provides that sort of abstract, modern support for the drama.

The dancing, and choreography by Ronald K. Brown, are really great. I suspect that the dance scenes, if tweaked and expanded a bit, will help enormously to make this into a Broadway hit.

Photo by Michael J. Lutch, courtesy of the American Repertory Theatre

The pacing is generally pretty good, though I did notice a bit of languor set in during the first act. Part of that can be attributed to occasional amorphous blocking of a large cast on an abstract and almost vacant stage; some of this could benefit from some further shaping. And, as well, the dancing does not get underway as quickly in the first act as it might. When it finally does, it is done with subtlety, fabulous gesture and a feeling of cultural authenticity; it adds real energy.

It is not clear where Diedre L Murray has adapted the musical score, which is a good indication of its effectiveness. My guess is that, among other touches, she’s added something to make the dance scences work well. In any event, they do, and Murray is to be congratulated on adapting the music in a way that appears seamless.

Suzan-Lori Parks’ adjustments seem subtle but useful. She’s done something to clarify Bess’ character and motivation, though it is not apparent exactly what it is. But the tweaks she has made seem useful for reinforcing Bess as a sympathetic, if still flawed and vulnerable, character.

The supporting characters are done well. David Alan Grier (Sporting Life) has a vivid and convincing stage presence, portraying the conman adeptly. (And wasn’t it Sportin’ Life in the original? Why that change?) Phillip Boykin (Crown) is a massive, resonant and convincing brute. And NaTasha Yvette Williams (Mariah) is a great don’t-mess-with-me community matriarch.

The music is exceptionally well played. I noticed, in particular, Leo Eguchi on the cello, but all of the instrumentalists carried off a difficult and intricate score with real refinement under Sheilah Walker’s direction.

Apparently the changed ending shown during previews was changed back by the time I saw the show. For all the hype about the ending, when it came it kind of fell flat – truncated and not dramatic enough. That may have been due to the sudden alteration. I trust, in coming performances, Paulus will transfigure it somehow.

All in all, this supposed re-visioning of Porgy and Bess felt like an artful editing job full of subtle but not drastic tweaks.

In the end, I agree with Sondheim – ditch the new title, put all the original authors’ names up in lights and under them say Newly adapted by Diane Paulus, Director, Susan-Lori Parks, Playwright, and Diedre L. Murray, Composer.

That would tell the truth about this quite faithful, subtly amplified and artful interpretation of the classic.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply