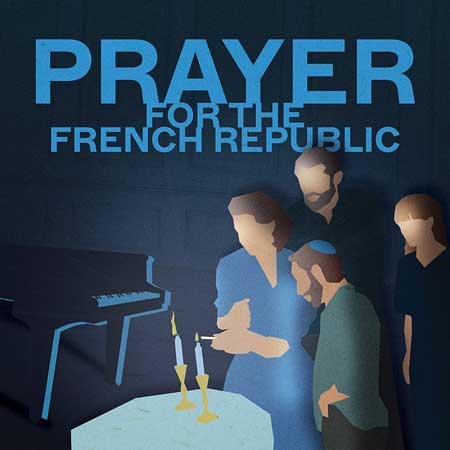

Play (2022)

by Joshua Harmon

Directed by Loretta Greco

Huntington Theatre Company

Huntington Theatre

Symphony Hall area, Boston

September 7 – October 8, 2023

Scenic Design: Andrew Boyce; Lighting Design: Christopher Akerlind

With Tony Estrella (Patrick Salomon), Amy Resnick (Marcelle Salomon Benhamou), Talia Sulla (Molly), Carly Zien (Elodie Benhamou), Nael Nacer (Charles Benhamou), Joshua Chessin-Yudin (Daniel Benhamou), Phyllis Kay (Irma Salomon), Peter Van Wagner (Adophe Salomon), Jared Troilo (Lucien Salomon), Jesse Kodama (Young Pierre Salomon), Will Lyman (Pierre Salomon)

Marcelle (Amy Resnick), a Parisian Jewish heir to a family piano dealership that her family has held for generations, and her Sephardic Jewish husband Charles (Nael Nacer), are the parents of Daniel (Joshua Chessin-Yudin), a young math teacher in Paris who has taken to wearing a yarmulke in public. At the outset of the play, Daniel enters bruised and bleeding, having been challenged and pummeled by some anti-Semitic toughs. A series of disputes ensues – about whether he should wear his yarmulke publicly – Marcelle thinks he shouldn’t – which evolves, over the course of the play, into a discussion about whether the family should emigrate to Israel. When, en route home from synagogue together, Charles experiences the hateful public response to Daniel, he is horrified and traumatized and immediately promotes the Israel emigration option. Meanwhile, Molly (Talia Sulla), a cousin of the family from the United States on a year-long visit to France, makes a strong connection to the family, and especially to Daniel. Daniel’s sister Elodie (Carly Zien), at first elusive and non-verbal, turns into an explosive and irrepressible voice for issues related to French anti-Semitism. Patrick (Tony Estrella), Marcelle’s brother, serves as the narrator and the foil, describing and introducing the series of events, and, as well, challenges Marcelle’s and Charles’ on questions about anti-Semitism and Jewish identity.

A coordinated set of scenes from Paris of the early and mid-1940s featuring Marcelle’s great-grandparents, Adolphe (Peter Van Wagner) and Irma (Phyllis Kay), her grandfather Lucien (Jared Troilo), and her father Pierre (Jesse Kodama in the 1940s, Will Lyman in 2016) are depicted, sometimes in alternation, sometimes in conjunction with the scenes from 2016.

Joshua Harmon’s early play Bad Jews was very funny and featured a kind of rawness and archness of dialogue mixed with an ingenious plotting that made it delightful and successful. A succeeding play, Significant Other, though dealing with more emotionally difficult themes, maintained that sense of humor that was shaded with greater emotional depth. Both plays felt coherent and persuasive. Harmon, in reflecting on the latter play, said he wrote it without the intent of being humorous, thinking it ultimately as a very sad play. Nonetheless, Harmon’s natural gift for humorous dialogue enabled him to give a light touch to what he thought was a difficult subject-matter.

Prayer for the French Republic is a very mixed bag. Its tonality varies so drastically from scene to scene that it is frequently unsettling in its somewhat random mixtures of tragedy, whimsicality and more vivid forms of humor. It seeks to address the very serious issue of French anti-Semitism but it does so with broad strokes that do not really capture the nuances of the matters that, during its more persuasive moments, it puts forward.

The play begins with Daniel wounded by a brutal anti-Semitic attack, and the tack that Marcelle, his mother, pursues is that he should not ask for trouble by wearing a yarmulke in public. But Daniel is passionate about publicly identifying his faith and undertaking ritual seriously, so much so that when sundown comes on Friday night he is urgent about getting the candles lit in time for the Sabbath. And yet, Daniel’s character is pursued with an odd inconsistency – his fascination with Molly leads him to want to stay in Paris and continue to be involved in the family piano business even when the family seriously undertakes the idea of emigrating to Israel. And, in a very odd turn amidst this rather serious subject-matter, Daniel winds up singing Bob Dylan’s Forever Young bare-chested to Molly. Though one might regard this as expressive of adolescent infatuation, the sequence is very strangely situated amid a subject matter that begs for more soberly thorough treatment.

When Charles returns from going to synagogue with Daniel and experiences the hateful looks of those who see Daniel with his yarmulke, Charles has a meltdown and declares he wants to move to Israel. Marcelle says that she cannot simply pick up her life, her medical practice, leave all of their friends, and abandon her aged father, to do that. As an exploratory gesture, Charles travels to Israel with Daniel for the weekend and returns, peculiarly and unexpectedly, with the declaration that he simply wants to live with Marcelle wherever it is. His terror of anti-Semitism, over a weekend’s trip, is magically transformed into an acceptance of hatred and danger wherever they may be. This transformation makes little sense given Charles’ recent explosion of anxiety, and there is no subsequent accounting for it in the narrative. This kind of random alteration without sufficient exploration occurs multiple times within this script.

The play relies on an alternate series of scenes set in the mid-1940s in Paris in the apartment of Marcelle’s Jewish great-grandparents who somehow have been overlooked in the Nazi scouring of Jews. This pair, Irma and Adolphe, manage a blithe neglect of what’s going on around them, bantering about the piano business and wondering, as though they were living on the moon, about what might have happened to their children. Despite the desperate times and what one might have thought was inconsolable worry on their part, their talk seems almost banal and irrelevant. There is barely any sense of urgency about what is going on around them which seems a very strange portrayal of the war years in Paris. The explanation of why Adolphe and Irma were not taken away to concentration camps seems highly specious. Additionally, the oddity of their not, during a period of two years, being able to extract from their son Lucien or their grandson Pierre, what has happened to them seems incredibly bizarre. Finally, Lucien breaks down, but it is short-lived and the revelations of Lucien’s and Pierre’s experience and the family’s losses go more or less unexplored.

The interleaving of scenes from the two different eras is overall not a successful ploy. Frequently the two sets of characters are put onstage together, which is supposed to be evocative and informative but is actually disorienting.

At one point the characters interact across time settings which again is meant to evoke but it just does not work.

of “Prayer for the French Republic”

Photo: Nile Hawver

Courtesy of Huntington Theatre Company

Though the primary set by Andrew Boyce is beautiful – a deep architectural space depicting an interior – and much of the lighting design by Christopher Akerlind is unique and interesting, there are aspects to the staging which are just distracting. At various points, when the family is sitting around the table, the table is set to rotate endlessly. I’m sure there’s some deep meaning to this, but in place of a deep meaning I just found it disorienting and without dramatic import. Additionally, there was, throughout much of the action, a kind of low level music or sound, barely distinguishable, that kept rumbling annoyingly to no apparent purpose. Again, I’m sure the intent was to convey something important about the setting and context but the effect is just distracting.

The most successful scene features Elodie, with Molly as a foil, holding forth in a rant about anti-Semitism, politics, Israel, the differences between being Jewish in France and in the United States, and the effect is hilarious. Carly Zien carries it off with breathless pizzazz. What Molly is doing there isn’t clear, but Elodie has to rant to somebody. This is the kind of thing that Harmon does best – a kind of manic comedy that feeds on somewhat earnest themes and explodes above them. In the case of this play, however, the subject-matter is a little too serious and the failure of the script to follow through on those themes makes the rant, though very funny, seem tonally out of place.

There are some seriously good actors in this production and they are able to show some of their wares. When Nael Nacer as Charles returns from the synagogue and explodes with fear and anxiety about the anti-Semitism that surrounds them, he is magnificently persuasive. Were his role written to support that kind of anguish throughout it would have given him the opportunity to shine consistently. Will Lyman, who shows up at the end as the elder Pierre, is also a wonderful actor who does his very best to convey something about the choices his character has made in staying in the family piano business, though one would be hard put to give a coherent summary of that explanation. Jared Troilo, as Lucien, is serious and affecting, but he is not given enough dialogue to express and follow through on his anguish. Joshua Chessin-Yudin as the young Pierre also conveys some significant gravitas when his role allows it, but, there too, the opportunity is not extensive. As Marcelle, Amy Resnick exhibits some complexity when she reacts viscerally and fearfully to the opening of a door to allow the prophet Elijah in at Passover. Worried about violent intruders, she begins to create the sort of multidimensional anxieties that the play outlines but never quite explores. Resnick does a reasonable job of gaining some entrance to those energies, but the episodic character of the script does not allow there much exploration of that sort as well.

The title of the play is taken from the scene in which Charles and Daniel return from the synagogue and note that interleaved in the traditional liturgy at the synagogue is a prayer for the French republic. It’s a poignant irony that Jews would be praying for the society in which they have suffered and continue to suffer the sorts of indignities that ignites this narrative.

The play ends with a long speech about all the kinds of hate the Jews have received. It feels like being hit over the head when the initial incident of Daniel’s brutalization has already spoken volumes. Harmon’s play indeed deals with important and moving issues, but, as in this case, much of the play is unwieldy. It could be much more eloquent if it focused its narrative and followed out the emotional strands that it lays out at the outset. If the play had done that, the hilarious parts would resound with a deep irony rather than feeling like small explosions of talented riffing in the middle of a tragic, but inconsistently drawn, background.

– BADMan (aka Charles Munitz)

Leave a Reply