Opera (2022)

Music by Kevin Puts

Libretto by Greg Pierce

Based on the novel The Hours by Michael Cunningham

And on the 2003 film based on the novel

Conductor: Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Metropolitan Opera, New York, Live in HD

December 10, 2022

Production: Phelim McDermott; Set and Costume Designer: Tom Pye; Lighting Designer: Bruno Poet: Projection Designer: Finn Ross; Choreographer: Annie-B Parson; Chorus Master: Donald Palumbo

With Renée Fleming (Clarissa Vaughan), Kelli O’Hara (Laura Brown), Virginia Woolf (Joyce DiDonato), Louis (William Burden), Leonard Woolf (Sean Panikkar), Richard (Kyle Ketelsen); Dan Brown (Brandon Cedel), Kai Edgar (Bug), John Holiday (The Man Under the Arch), Denyce Graves (Sally), Kathleen Kim (Flower Shop Proprietor), Sylvia D’Eramo (Kitty, Vanessa), Tony Stevenson, Atticus Ware, Patrick Scott McDermott, Lena Josephine Marano, Eve Gigliotti

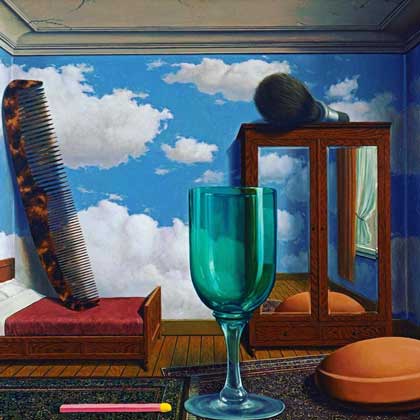

“Personal Values” (1952)

Image: Courtesy of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

The setting is actually three settings: in 1923, 1949 and 1989. Each of the three noted divas who head up this production is featured in one of those time settings. In 1923 in London, Virginia Woolf (Joyce DiDonato) is wrestling with the creation of her great novel Mrs. Dalloway and wrestling, as well, with suicidal thoughts. In Los Angeles in 1949, Laura Brown (Kelli O’Hara) is reading Mrs. Dalloway and totally taken with its message and tone; she also wrestles with her ability to stay with her current life, as wife to Dan (Brandon Cedel) and mother to Bug (Kai Edgar). In New York in 1989, Clarissa Vaughan (Renée Fleming) is preparing a party for her dear friend Richard (Kyle Ketelsen), a poet and novelist who is dying of AIDS. Though the book and the film which form the basis for the opera provide more distinct boundaries between their narratives, the opera innovates in interleaving these liberally – sometimes with multiple time-frames staged concurrently at different levels of the set, or at other times – particularly at the end – when all boundaries seem to disappear.

It would be difficult to praise this incredible production too highly: the music is lush and inventive, the libretto is thoughtful but hang-loose in an appealing way, and the orchestral playing and singing are absolutely first-rate.

Where does one begin? For no other reason than whim, begin with conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s flower patterned shirt, an innovation for a Metropolitan Opera conductor indicating the advent of new ideas and approaches. This does not signify, to be sure, an artistic coup d’etat, but a distinct indicator of an evolution. Nézet-Séguin, supported heartily by Met General Manager Peter Gelb, leads this innovative trend with personal warmth, insight, and with sensitivity to cultivating the traditional repertoire as well as breaking new ground. The current production represents a part of a wonderful new turn – the work itself, by a relatively unknown but terrific contemporary composer and lyricist, and the risk by the Met to make it one of its featured Live in HD productions of the year.

According to the interview conducted by host Christine Baranski with Fleming, DiDonato and O’Hara during intermission, the idea of doing this opera was originally promulgated by Fleming. She says that she had been touring with composer Kevin Puts doing a program based on the painter Georgia O’Keeffe and Puts raised the idea of doing an opera. Somehow together they came up with Cunningham’s The Hours as a basis for it. Fleming promoted the idea to the Met, Gelb and Nézet-Séguin supported of the idea, and O’Hara and DiDonato were soon enlisted to join in the project. Puts and librettist Greg Pierce worked on the opera largely during the COVID pandemic; today’s innovative and moving production is the result.

Renée Fleming (Clarissa Vaughan)

Kelli O’Hara (Laura Brown)

It’s an embarrassment of vocal riches, with the three principal singers – Joyce DiDonato, Renée Fleming and Kelli O’Hara – sitting atop a well-funded account of collective artistry. DiDonato and Fleming are long-time leads at the Metropolitan Opera and highly seasoned operatic performers, though Fleming has not appeared at the Met since 2017; so this is a much-welcomed reappearance. Both Fleming and DiDonato, as expected, do wonderful work here. Though wonderful and capable throughout, Fleming’s most compelling vocal power grows as the performance goes on, and as it approaches its end reveals the truly penetrating majesty of her tonalities. The real surprise here, however, is Kelli O’Hara, a Broadway star of many years who had operatic training early on but who is not specifically known for her work in opera. She flies here; she is just terrific. Her voice reaches peaks with such grace and poignancy and her stage demeanor captures the incredible pathos of her role. Both in solos and in ensemble, her vocal work is stunningly good.

Supporting roles are also very well sung. Most prominent among these are Richard (Kyle Ketelsen), whose reverberant baritone soars above his role as a terminally ill AIDS victim, and Leonard Woolf (Sean Panikkar) who equally floods the room with his baritone wealth. Perhaps most surprising is Laura Brown’s young son, Bug (Kai Edgar) who sings quite a bit and does it flawlessly and wonderfully. Also surprising and unexpected is John Holiday’s terrific countertenor as The Man Under the Arch.

The dominant presence of a kid who sings extensively and a countertenor in a contemporary opera represent just a couple of the innovations in this work. In addition to the fabulously internetworked narrative and the unexpected ensembles it creates, the music is lush and varied and also is tailored to frame each of the time settings it depicts. Most obviously, the 1949 setting is filled with jazzy riffs, but coloration is used interestingly throughout.

The dramatic side of the production as overseen by Phelim McDermott is innovative and dynamic. The set by Tom Pye is not imposing but complex, with pieces coming and going, rising up above one another, disappearing or turning around at will. And there are projections (by Finn Ross) to boot, amplifying the sets and enhancing the deft lighting overseen by Bruno Poet. The chorus overseen by the everpresent Donald Palumbo is abundant and wonderfully present, and the choreography by Annie-B Parson is highly ingenious and creates a great sense of ongoing dynamism without having to pause for the more traditionally, often set apart, operatic dance scenes.

Though it’s a little difficult to hear some of the orchestral nuances in the Live in HD productions – it is really a different musical experience if one can actually GO to the Met, but one does what one can – the orchestra played flawlessly and energetically. Conductor Nézet-Séguin is so appealing he seems to create an additional glow around the Met orchestra, already before his appearance one of the best orchestras in the world.

Image: VISTA Telescope, Chile

Some more detailed notes from the performance:

Act I

Atmospheric trilling as the chorus appears. Texture of a sound wall shaped interestingly as voices emerge subtly. Repetition of phrases like the flowers give a foretaste of Woolf’s modernism and the evocation of the artistic process in utero. The gestural choreography is great. The scene is all about the opening line of Mrs. Dalloway: “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself” – a great, complexly knotted but redolent opening.

Now we’re in the New York City in 1989: Clarissa (Renée Fleming) is buying flowers for Richard’s party. John Holiday’s (The Man Under the Arch) countertenor is as wonderful as it is unexpected. The scene set in Washington Square with chorus members striding back and forth across the stage is terrific and dynamic, seeming like much more of a crowd than it is.

Virginia Woolf (Joyce DiDonato) drifts in, 1923. She is starting a new novel. Interestingly static choreography – dancers not moving but perched in strange positions. Then back to 1949 with Clarissa in a flower shop, paired with the proprietor, capably sung by Kathleen Kim, now with more urgently orchestrated accompaniment. A great rapping tingle slides the transition back to 1923. Muses enter swirling, with Puccini-like dancing tones from harp and or cembalo, with the vocal undertone rumbling: if she can keep quiet, productive and strong, she may pick up her pen., and a wonderful staging of Woolf’s entry into writing the opening of the novel.

Now 1949: Laura Brown (Kelli O’Hara) is perched above, reading Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. One more page, she sings to herself, obsessed with the narrative, so I can lose myself, no – find myself. On the phrase squeak of the hinges, O’Hara gives a great vocal twist. A complex and interesting duet between O’Hara Brown and DiDonato’s Woolf. Slippery strings as Laura’s husband Dan (Brandon Cedel) and their son Bug (Kai Edgar) appear. What a great singer Kai Edgar is! Brandon Cedel’s Dan also has a beautifully rich voice, and is also very tall! O’Hara is exquisite in the high registers, kind of amazingly so. Laura laments over the possibility of Dan having an affair, but realizes her own depressive inadequacies, his wife aloof, always reading. A vivid trio with Laura, Dan, Bug, along with the chorus, and a great tense moment between Laura and Bug.

1923: Woolf muses over a novel based on a single day: distant sounds wading through the hours. In 1989, Clarissa remembers: on this corner (of NYC) you argued with Richard and ended it. Cruel, Clarissa. Harsh. Then Richard’s apartment. He calls Clarissa Mrs. Dalloway, and we welcome Kyle Ketelsen’s resplendent baritone. A tender moment with Richard and Clarissa. Love the jazzy musical transitions to 1949 Los Angeles! This kid Kai Edgar (Bug) is great! As well as delivering exquisitely vocally, O’Hara provides an appropriately frazzled, tragic sense to the character. She tries to bake a cake with Bug for Dan’s birthday, but Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway is not far away from her mind. The troupe of dancers wafts in and out among these goings-on – fabulously.

1923: Virginia’s sister Vanessa threatens to appear with her children. And then, in 1949, the appearance of Laura’s friend, Kitty (Sylvia D’Eramo). Kitty and Laura kiss, a shock to Laura. 1923: Virginia, writing Mrs. Dalloway says that someone will die at the end of the day. Lush orchestral reflections, while, in 1949, Kitty goes to the hospital for serious illness. O’Hara’s voice is astounding! 1989: quite a duet – Clarissa and her partner, Sally (Denyce Graves) – with choral background – incredibly complex and seeded with agitated orchestration.

The Act I finale approaches – stupendous. Wonderfully suggestive choreography, with all three leads leaving to go somewhere. Where are you going?, ending tumultuously.

Act II

Cheers for Yannick and the orchestra, most deservingly.

A light birdlike entrance. Dancers carrying pillows. Laura in a hotel room in Los Angeles, with effective small sparkling projections, then sunlight. O’Hara’s voice rises into the stratosphere. The bellhop is shiningly rendered by countertenor John Holiday in a new turn. O’Hara conveys a great tragic sensibility; a beautifully poignant duet between Virginia in 1923 and Laura in 1949 with actively lubricated orchestrations beneath.

Leonard Woolf (Sean Panikkar) appears – wonderful – a despairing lament over Virginia’s suicidal tendencies. Clarissa (in 1989) enters, with an eloquent and rich soliloquy. She inadvertently meets Louis (William Burden) an old friend of hers and Richard’s who reports with Pierce’s wonderfully offhand lyric I’m here for a conference on the future of theater, blah, blah, blah. Terrific! A drape drops and projections of the beach at Wellfleet appear, reminiscently. Richard (in Ketelson’s wonderful bass/baritone) to Clarissa, eloquently: He wanted me for my body and you for everything else.

Virginia crumbles and Laura comforts herself. Three kids enter singing in high-pitched harmony, wonderfully! Identified as angels, it is really Virginia’s sister Vanessa (Sylvia D’Eramo) arriving with her children (including, by the way, the young Quentin Bell who later became famous for memoirs about his extended family).

A long orchestra interlude before Richard’s apartment. He’s sitting at a window ledge and threatening to jump. Fleming’s Clarissa now in resplendently full voice, with a scintilliting score beneath and a penetrating, repetitive beat – is it a piano? Richard to Clarissa: You’ve been so much more than my best friend.

1949: Laura comes home to Bug, where Mrs. Latch (another appearance by Kathleen Kim, who played the flower-seller earlier), the babysitter, is with Bug. 1989: Clarissa laments Richard’s fate to lush orchestral washes. Virginia: I might call my novel “The Hours”. 1949: Bug is worried, since his mother has been away, that she, like her friend Kitty, has cancer. Fleming’s voice really comes into her own as the opera nears its conclusion. Laura’s husband Dan claims – again in Pierce’s cutely repetitive but effective lyrics – that he is awfully, awfully, awfully, awfully happy. 1923: Virginia declares that someone in her novel will die and it must be Septimus.

Change to the final scene.

The formerly interleaved time frames have now totally melded. Virginia, Clarissa, Laura together in the final scene: We go on living. All the hours. A tremendous final trio. Here is the world and you live in it, and you are not alone with a wonderful interlaced declaration and you try with a filling pool of sound beneath.

The audience cheered as it rose to immediately to its feet, a highly deserved appreciation.

– BADMan (aka Charles Munitz)

Leave a Reply