Musical (2019)

Music, Lyrics, Book and Orchestrations by Dave Malloy

Based on the novel by Herman Melville

Developed with and directed by Rachel Chavrin

American Repertory Theater

Loeb Drama Center, Harvard University

Harvard Square, Cambridge, MA

December 3, 2019 – January 12, 2020

Music Direction and Supervision: Or Matias; Choreography: Chanel DaSilva; Scenic Design: Mimi Lien; Costume Design: Brenda Abbandandolo; Lighting Design: Bradley King; Sound Design: Hidenori Nakajo; Puppet Direction: Eric F. Avery

With Dawn L. Troupe (Father Mapple, Captain Boomer, Captain Gardiner), Manik Choksi (Ishmael), Kim Banck (Sailor, Singer, Carpenter), Starr Busby (Starbuck), Andrew Cristi (Queequeg), Ashkon Davaran (Sailor, Elijah, Blacksmith), Morgan Siobhan Green (Pip), Anna Ishida (Flask), Matt Kizer (Tashtego), J.D. Mollison (Daggoo), Kalyn West (Stubb), Tom Nelis (Ahab), Eric Berryman (Fedallah)

with the Cast and members of the audience

in “Moby Dick”

Photo: Maria Baranova

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

Anyone who has read Moby Dick knows it’s about an obsessed Captain, Ahab, who’s after a great white whale. Narrated by a seaman, Ishmael, the tale of Ahab’s vengeful possession of the determination to destroy Moby Dick provides the large arc of the drama. Internal to it are various smaller dramas about the various seaman on board, and particularly about the mate, Starbuck, who becomes increasingly aware of Ahab’s growing derangement.

But, one who has read the book also knows that, despite its incredible length, there’s a lot there that has very little to do with the plot itself. There are large swaths of it which are simply descriptions and analyses of whaling and compendia of interesting tidbits about whales. The narrative doth go on, but not necessarily to develop the character of Ahab or to investigate the dimensions of his relationship with the crew. Though, indeed, Moby Dick is a great work of world literature, one must regard it as something different than a novel per se. Much like James Joyce’s Ulysses or Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, it is indeed an epic of inestimable cultural value, but that is not due, in large part, to the novelistic finesse it displays.

Interestingly, Dave Malloy, who wrote the book, lyrics and music to this show, not to mention doing the orchestrations, had chosen another of these literary non-novelistic epics, War and Peace for one of his last musicals, Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812 originally produced at the ART in 2015 and then sent to Broadway for a durable run there. Given the nature of these beasts, so to speak, one would expect that Moby Dick would be headed in the same direction.

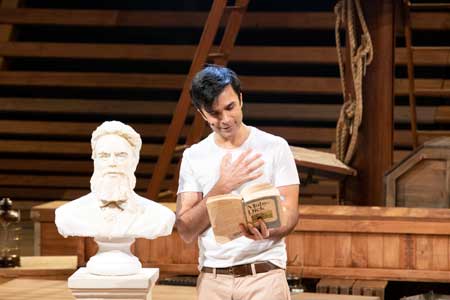

with a bust of Herman Melville

in “Moby Dick”

Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

There is much to like in this musical and production, though I found the first half of it significantly more captivating than the second. Some of the music, though seeming almost entirely eclectic, is quite catchy; the lyrics are somewhat straightforward, though at times they take interesting turns.

And much of the staging is truly brilliant. For this production, Chanel DaSilva who had done the choreography for the ART’s excellent The Black Clown, does it here as well; it’s generally wonderful, as is much of the staging. And there are great additions, like a superb section in which various puppets and props representing whales and associated materia, designed by Eric F. Avery, are bandied about. It turns the section named Cetology, very long in the book and which is all about whales, fascinating, entertaining and enlivening.

There is also a pretty long section in the first part in which about twenty audience members are brought on stage to participate in a whaling expedition. Magically, boats appear from below stage, audience members are donned with red rain gear, and water spouts shoot up. Cast members transport the audience members who are seated in the boats for a spin around the stage and everyone seems to have a good time. It’s a gag that’s very reminiscent of The Blue Man Group at which performances audience members – not as many – are outfitted with raincoats and included in the messy action. Though one might think it’s a bit derivative, it works pretty well here.

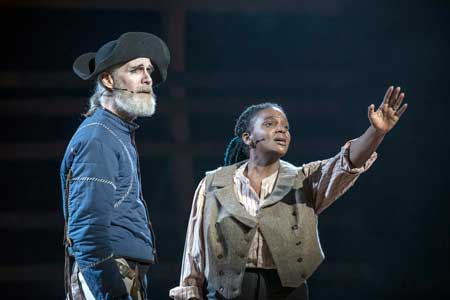

Starr Busby as Starbuck

in “Moby Dick”

Photo: Maria Baranova

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

There’s also a fun and messy segment about processing spermiceti that has the cast and the raincoated audience members sitting in a circle mushing the stuff around in bowls and then grasping hands with one another. The indulgence of this section is that it plays on a common misinterpretation of the sailors in the mid-nineteenth century that spermiceti was actually the sperm of the Sperm Whale. It’s actually not, but, rather, a substance found encased in the head of the whale and thought to perhaps have something to do with buoyancy. Conveniently, the substance is white and kind of waxy, which enables this musical to refer to it as “sperm” and have a good old time with the confusion. But it does seem like a bit of an indulgence to play upon the audience’s likely ignorance of this and go for a slightly racy impression.

The cast, except for Ahab, is non-white, which seems to be making a point about domination, subservience, ethnicity and democracy. That intention is well-taken, and the motif, made popular by Lin-Manual Miranda in Hamilton (2015), carries over here as well. In the novel, the non-white members of the crew play a very distinctive role and are highlighted by their non-whiteness; that stark relief in which Queequeg or Tashtego rise up in the book gets somewhat lost in this notion of making practically all of the cast non-white. Nonetheless, the identification of the whole crew with the non-white members seems, in fact, the basic idea, and in contradistinction to the stark whiteness of Captain Ahab and the object of his obsession. In Hamilton the whole cast takes on the mixed ethnicity of its hero; here, in Moby Dick, the whole cast takes on the ethnicity of those strikingly ethnic members of the crew. It’s an interesting technique, clearly makes a point, and gives good roles to talented people of color in a work that, more traditionally cast, would not. One still might ponder whether that choice makes less vivid some of those significant distinctions from the book.

Things move along quite well in the first half. One doesn’t get too much about Ahab, though he stands around a lot looking gloomy and obsessed. Other than that, one doesn’t really know that much about why he’s obsessed, except that Moby Dick had eaten his leg in a prior encounter. But we don’t hear a great deal about what’s going on under the hood with Ahab.

That all seems okay in the first half, but the hens come home to roost in the second. The problem, in part, is with the novel, which, surprisingly, given its girth, does not give all that much about Ahab; one is left with an image of a severe and obsessive captain who goes off the rails, but not much more than that. The musical also seems short on that matter, but it’s not really its fault, though one might have hoped that it would, through the magic of musical lyrics, flesh out the texture of Ahab’s character and associated insanity a bit more.

In the second half of this production, instead of trying to make some sense of Ahab’s nuttiness, there is an overly long section about Pip, a cabin boy who gets lost at sea. It encompasses several attenuated songs and a lot more than a few minutes of stage time, which does not serve the rhythm of the overall drama. Including the Pip episode, but in a more abbreviated form, would seem like a better choice.

The illness and death of Queequeg, an expert harpooner originally from the South Seas, is handled more economically and deftly. Through depicting his strong negative visceral reaction to the murder of a mother whale nursing her young, his acute decline becomes vivid and poignant.

with the Cast

in “Moby Dick”

Photo: Maria Baranova

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

The acting, and dancing and singing, are extremely good all around. A great thing about this production, in keeping with the sense of what it portrays, is its democratic sensibility; each cast member gets a moment to shine, whether in a singing or dancing solo, or as a rapper or stand-up comedian. That embrace of democratic sensibility nurtures the subtext of this great American novel, which is really about the way in which an entire diverse crew, originally inspired by democratic spirit, is led to disaster by a maniacal leader.

The greatness of the novel lies, in part, in demonstrating how each character in that diverse crew has an integrity that gets taken over and manipulated by the crazed leader. Were they led by a Captain Gardiner of The Rachel – portrayed as a far saner alternative to Ahab – how different their sense of engagement and associated destinies would be. Clearly, this production enables one to consider how timely and relevant such concerns are.

Though singing by almost all of the cast is clear and wonderful, the score is not always straightforward and there are at various points in some of the solo outings some intonation issues that border on the uncomfortable.

Overall:

The first part of this show is very good – I found it more deftly crafted than Malloy’s earlier Natasha and Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812. Even with the long audience participation gag and a pretty long stand-up comedy routine by Eric Berryman that breaks the fourth wall with contemporary language and perspective, it all works pretty well.

The second part could be trimmed significantly, while still preserving the important dramatic elements – the collapse of Ahab’s sanity, Starbuck’s realization of that, the tragedy of Pip’s loss at sea, and the death of Queequeg. The poignancy of these various themes might be served by some deft editing that could enable the overall length – a weighty three and a half hours that begins to wear on near the end – to be lightened a bit.

One must certainly commend Dave Malloy and the ART for taking on this great work in an interestingly improvisational, pluralistic, and entertaining way, and helping, as with Natasha and Pierre and the Great Comet of 1812, to make one of the world’s great epics just a bit more accessible to many who might not have yet wandered through its significant expanses, and to offer a stimulating recapitulation to those who have.

– BADMan (aka Charles Munitz)

Leave a Reply