Three Short Plays

by Samuel Beckett

Directed by James Seymour

Commonwealth Shakespeare Company

Presented by BabsonArts

Sorenson Center for the Arts

Babson College, Wellesley, MA

April 27 – May 7, 2017

Rough for Radio II

With Will Lyman (Animator), Ken Baltin (Fox), Ashley Risteen (Stenographer)

The Old Tune

With Ken Baltin (Cream), Will Lyman (Gorman)

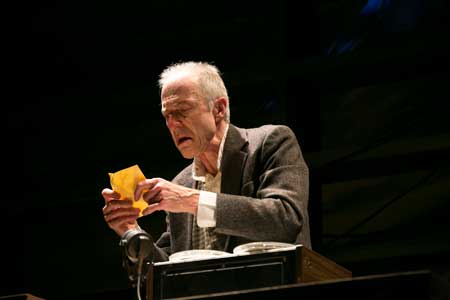

Krapp’s Last Tape

With Will Lyman (Krapp)

Ken Baltin as Cream

in “The Old Tune”

Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

Courtesy of Commonwealth Shakespeare Company

Rough For Radio II, which opens this delightful trio of Beckettian tastes, was originally written as a radio play. Beckett penned it in 1961 in French and then translated it into English for a production on BBC Radio in 1976. In that 1976 production, playwright Harold Pinter played the role of Animator.

In the current production, the play is done in silhouette, a quite effective adaptation of the original, affording some visual supplements only suggestible on radio. At one point, notably, the stenographer removes her clothes, creating a provocative shadow and a dramatic response from Animator who pines that were he only forty years younger…

Even though it received some notable productions, apparently Beckett regarded the play as unfinished and merely as a kind of sketch.

Nonetheless, it offers an intense, though inchoate, kind of drama, in which the triad of Animator, Stenographer and Fox, who remains pretty much hidden throughout, exchange a series of quizzical references. Animator speaks predominantly with urgency and violence, Stenographer desperately tries to mollify him, and Fox simply struggles.

Here Lyman as Animator is ferocious, Risteen as Stenographer effectively erotic and solicitous, and Baltin appropriately submissive.

Will Lyman as Animator

Ken Baltin (unseen) as Fox

in “Rough for Radio II”

Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

Courtesy of Commonwealth Shakespeare Company

The overall shape and tone of the piece is a violent rebellion against aging and diminution in which Animator tries desperately to force Fox to do his bidding while finding himself less than efficacious. Stenographer reminds him of the echoes of desire come and gone which he can no longer honor, and much as he rails against Fox and the world which betrays him, he fights a losing battle.

The Old Tune, alternatively, is an accessible and charming piece that simply involves two older men meeting on a bench and exchanging a series of reminiscences. Their losses of memory and capacity are profoundly evident, but they persevere – continuing to move on into later life with an existential urge surrounded by vacancy and incapacity.

Interestingly, this is a small Beckett piece that has all the earmarks of his demonstratively existential works while remaining entirely naturalistic. That straightforwardness with which the setting brings forth all the traditional Beckettian themes – emptiness, vagueness, lostness, confusion, fatality – provides an undeniable charm to the piece that complements its existential reverberations.

Baltin and Lyman are just terrific in this piece – they fit together like puzzle pieces, exchanging their quips with the grace of tennis masters handing off the ball to one another. This central part of the triplicate Beckett sandwich is a particular delight and provides its demonstrable effect by being both vividly literal and metaphorically rich.

I once heard noted playwright Tom Stoppard say that in some part of his soul he wanted to believe that Waiting For Godot was really just about a group of hobos having an encounter. Here, in The Old Tune, one engages with a scene that one can easily appropriate as just two old guys reminiscing. At the same time, one can easily open the allegorical ear to hear every quip touching the familiar Beckettian nerves. One doesn’t have to want, as did Stoppard about Godot, to believe that The Old Tune is just about those old guys because it so vividly is. And, at the same time, it’s about a lot more.

Krapp’s Last Tape, the most famous of the three plays, was written in 1958 for actor Patrick Magee after Beckett heard Magee reading Beckett’s works on the radio. It inspired what Beckett regarded as some of his most autobiographical writing.

Will Lyman gives both a very funny and a tortured rendering of Krapp. Lyman’s nose is vividly reddened for Krapp, obviously in reference to the avowed drinking issues which Krapp owns up to and which presumably beset Beckett as well. It also suggests clownishness, a vivid element of the character who stumbles and careens through life, avoiding catastrophe at every turn, often with desperate amusement.

Lyman’s Krapp humorously goes through the motions of unlocking a desk drawer several times to remove bananas which he proceeds to peel with great drama, and then to eat. Between the bananas he goes to his tape deck to review a series of recordings about his own life featuring Lyman’s voice-over as Krapp recounting various grim aspects of his life.

in “Krapp’s Last Tape”

Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

Courtesy of Commonwealth Shakespeare Company

Again, the tone is replete with a combination of industry and vacancy, an earnest recounting of the details of life and a throwing up of one’s hands at the absurdity of the various turns it takes.

In this completed layer of the tripartite Beckett sandwich, the main character faces himself in echoes, lonely, desperate and pulled between the richness of his recounted life and its disappointments, facing it with sighs and punctured smiles.

Lyman gives a persuasive tragicomic performance, his daunted and benighted Krapp a counterbalance to the ferocity of the tortured Animator from the first play. Those two formulations, effectively embodied by Lyman, serves to frame the sweeter and more vulnerably poignant characters of the middle part, themselves filled with memory but diminished by life, hovering somewhere between frustration and dauntedness as they replay their lives and squint at what lays before them.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply