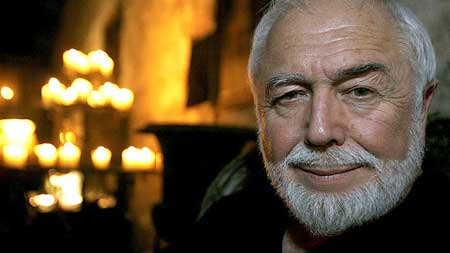

Photo: Abir Sultan/Flash 90

I spoke with noted Israeli playwright and stage director Joshua Sobol on March 7 about his upcoming residency in Boston (March 20 – 31) sponsored by Israeli Stage. What follows is adapted from that interview.

The world premiere of David.King, a new play by Sobol, will be given in a staged reading at Wellesley College on April 5.

When we spoke, Sobol was in the middle of rehearsing a production of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice in Israel.

CM (Charles Munitz): I read a little about the production of The Merchant of Venice from the time it was in Illinois. (Sobol directed a similarly staged version in Bloomington, IL in 2002 as part of the Illinois Shakespeare Festival. Here’s a review of that production from “The Chicago Tribune”.) Interesting that you were able to portray Shylock’s daughter as leaving the faith without portraying it in negative terms.

JS (Joshua Sobol): My idea was the idea that Shylock understands he’s doomed because, under the Italian Fascist regime (Sobol sets the play in 1938), when they come to ask for money it’s like the Mafia visiting you. So he knows his days are numbered and he wants to save his daughter. He prepares everything for her escape but she has to pretend vis a vis her Christian friends that she hates her father and that she’s going to convert to Christianity. I managed to get the idea across without changing a word of Shakespeare’s text. When Shylock pushes her to the veranda of the house to give her fiery speech, she does so for Lancelot (a clown in the traditional version of the play), a secret agent of the regime, to hear it. It’s all done very falsely in order for Lancelot to hear it and to say to the authorities that Jessica is ok, she’s one of us.

CM: It’s a very clever way to couch that and to explain it.

JS: I consider the play originally as a play about an anti-Semitic society. I imagine Shakespeare understood quite well what it means to discriminate against a minority. What I wanted to make clear is that there’s no justice in that society. When in Act IV, Portia comes and reverses the bond between Shylock and Antonio – I have Portia played by a man – the idea is that in a fascist regime, a gay person couldn’t go on living openly. Here, Portia’s father says OK, you’ll have to marry a man and live like a woman, to cross dress, etc. When Portia gets the news that Bassanio, her recent new husband, has a connection with Antonio, she wants to go to Venice and see what that relationship is. So she undresses as a woman and reveals herself as a man and discovers that Bassanio has a love affair with Antonia, a woman in my production, who has to dress as a man to function in mercantile society. It’s about a society in which you’re ok if you conform. When Portia realizes that Bassanio and Antonia are having a love affair, she directs Shylock to cut a pound of flesh. The mob, led by Il Duce, violently attacks Portia and makes her change the verdict. I wanted to show that under duress, a head of state will fight against the judiciary.

CM: Can you imagine such a thing happening!

JS: So, this is a play about fascism and a society which began as a normal society but which undergoes a process and ends up as a fascist society.

CM: So that brings us right up to the present and your visit to the Boston area. Guy Ben-Aharon (Producing Artistic Director of Israeli Stage) has arranged a great opportunity for you to present your ideas to the audience in the Northeast. How did you come to meet Guy?

JS: He contacted me about three years ago and we spoke about my coming to Boston. And that I would bring a new play to workshop and do a rehearsed reading of the play.

CM: What’s the name of the play?

JS: David.King I inverted the order – in my interpretation of King David, he didn’t want to be a king. The events forced him to finally accept the throne. After he kills Goliath, the people are full of admiration for him. But King Saul is very apprehensive and concerned that David will take over the kingship. So King Saul starts to persecute David, but David, on two or three occasions, when he has the opportunity to kill Saul, finally tells him I don’t want to kill you, I don’t want to become king, so don’t continue to run after me. Finally, when he becomes king of Judea, King Saul’s general, Abner, offers David the throne over all of Israel, but David is not eager to take it. He finally accepts it, but when Absalom, his son, rebels against him, and Yoav, David’s head of the army, says let’s finish him off, David says No, no, let’s run away to the desert. Yoav doesn’t understand it, but my understanding is that David had the best time of his life in the desert. So, at the end of his life he abdicates the crown and gives it to Solomon who protests But father, you’re the king. And David responds by asking what does it mean to be a king and what’s the importance of power?

CM: An important theme of humility, reminding one that the capacity to govern comes along with the capacity to control one’s ego.

JS: The Bible portrays him as a musician and as a poet. For him, those are more important than the crown. The people made a great king of him, but why? Because he wasn’t eager for power but ready to give it away on any occasion. When I wrote the play I had John Lennon in mind – you could imagine people offering him to be king of England but no doubt he’d respond I’ve got more important things to do.

CM: In the Vilna Trilogy (Ghetto (1984), Adam (1989), Underground (1991)) there’s a related theme about the compromises and difficulties of leadership and how it ties in with the whole issue of art. There’s also a question of moral ambiguity. David is in the same position as Jakob Gens in Ghetto.

JS: Jakob Gens was an officer in the Lithuanian army, so he had a background in the military. He was also married to a Lithuanian woman, not a Jew. He lived outside the ghetto and could have stayed outside of it but when the Germans pushed the Jewish population into the small ghetto, Gens told his wife I could be very useful to my people because I speak Russian, German and Lithuanian and I have good friends among the Lithuanian officers. So he entered the ghetto, eventually becoming head of the Judenrat and the head of the ghetto. He tried to understand the logic of the Germans – why they were carrying out the extermination of the Jews while carrying out the war on two fronts? He saw there was something illogical and that the Germans were killing a population of potential workers for the war effort. He was very practical and pragmatic and tried to convince the 15000 Jews who remained in the ghetto that the more productive they could be would help to ensure their survival. And to make them productive, he saw that it would be helpful to normalize their lives, and that having a theater would help that. (He also opened an orphanage, a school, and supervised the hospital.) One of his friends was an actor and he enlisted him to open a theater. Gens was able to get working permits for the actors. So they established the theater. All of the performances were overbooked. They had 300 seats in the theater but they always sold more than that. When they celebrated the 100th performance their records showed they had sold 35,000 tickets. So, the play is about the function of theater as a means of spiritual resistance. It helped to raise the morale of the people, even though it was clear to them at the time that the Nazi project was to exterminate the Jewish people.

CM: Elie Wiesel came down pretty hard on you for this play. Why?

JS: That was when the play was performed in NY (in 1989). Later he and I met and he was very friendly and he spoke differently about the play. What initially shocked him was that the play brought to the stage some characters who were not celebrated as heroes. There is a character, Weisskopf, who is very entrepreneurial who opens a shop to repair German uniforms – he becomes a millionaire in the ghetto. He did play a positive role by employing 150 people in the ghetto. When Genz wanted to add people to the shop to save more people, Weisskopf refused. They had a clash and Gens had Weisskopf arrested.

CM: Both are historical characters?

JS: Yes. So the play brings these characters to life as they were, and did not glorify some personalities and events – it was grey, not black and white.

CM: Guy says that you’re a playwright who deals with political issues in a deft and interesting way. It’s not polemics which rule your art but indirection and suggestiveness. The theme of your lecture is challenging authority through art. Can you talk about that?

JS: My approach in general is if I write about an historical issue I do a lot of research beforehand. The theater is where you tell stories that are meaningful for the community. In order to do so, you have to be a person of your time. What lies ahead for our people? is a crucial thing to ask. Also finding historic roots for current events and states of affairs is important. For example, I felt there was a rise of fanaticism in Israeli society and we were divided between people who sought a peaceful solution with the Palestinians and the Arabs, and then there was a big chunk of the population that preferred to continue the occupation of the territories. The latter, I believe, endanger our future, so I’m inclined to look back to see where that kind of zealotry or fanaticism comes from. I detected some of it in the rebellion of the Jews against the Romans in the era of the Second Temple. It was really a minority at the time who effected a rebellion against the Roman leaders. Some religious leaders like Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakkai were opposed to that rebellion, claiming it was a suicidal effort. The Zealots prevailed and led the Jews into an open war with Rome that eventually led to the destruction of the Second Temple and to the loss of Jewish independence. So, there is a tendency in our collective history and subconscious towards self-destruction that manifests itself as zealotry and fanaticism. I feel that the same thing influences Israel today. So I wrote a play called The Jerusalem Syndrome about that. It opened at the Haifa Theater in 1988 and the result was a huge blow up because the extreme right wing was opposed to that interpretation of our history and I had to resign from my post as the artistic director of the Haifa Theater.

CM: Because of the opposition of the Israeli right.

JS: Yes.

CM: What was it about The Jerusalem Syndrome that offended people so deeply?

JS: It went against the official narrative about the revolt. As a child, I learned that the rebellion against Rome was an attempt to regain our freedom as a people. The war was portrayed as heroic, even though it ended up in a catastrophe. What I found out through research was that it was an unnecessary war. Under the Pax Romana, there was a kind of peace akin to that of the Cold War. For a long time, whoever tried to shake off the Soviet occupation got their backbones broken. As well, during its main period of dominance, all the attempts of revolts against the Roman Empire failed – not just in Judea – but the Gallic revolt failed, and in what is now Romania also. The Roman Empire crushed them. What provoked the violent reaction about the play was that it opposed the standard narrative. People just didn’t want to accept it. It provoked a lot of controversy, on both sides, and even though I lost my post I thought it was a powerful theatrical event.

CM: So there was no real opportunity for dialogue with that opposition. You always think of Jews as capable of engaging in dialogue…

JS: I think that Judaism is a lot about arguing, about discussing, about not agreeing automatically. But sometimes you touch a raw nerve and the reactions are very violent.

CM: Would you associate that kind of reactivity with the beginnings of fascism?

JS: Yes, the danger is there. When the government starts to change the laws to suppress criticism or opposition and when the government starts to fight against the judiciary, against judges who are not comfortable for the rulers, then of course there’s the danger of fascism, which is about paranoia, about stirring up all kinds of fears among different sectors of society according to the idea of divide and rule. So when the regime tries to stir up one sector against another and to foster open hatred, then we are facing a danger.

CM: You’ve said you’ve seen this happen in Israel. I assume that everyone in Israel has been watching what’s going on here.

JS: Yes, very closely.

CM: How do you associate the effects of what’s going on here now to what’s going on in Israel?

JS: The extreme right wing in Israel celebrated the success of Trump and believe that he will allow immediately the annexation of territories, to establishing more outposts in the Occupied Territories. On my Facebook page I wrote a post the day after Trump was elected saying that I thought the right wing would end up missing President Obama. With Obama, one knew where one was and I think he was very honest in what he said and meant – he carried his heart on his tongue. With Trump, he’s unpredictable and his tendency is not to be so interested in what’s going on in our region. When he met Netanyahu at the press conference, he said you want one state, you want two states, whatever. Whatever!

CM: You couldn’t have written a play that was better. How do people in Israel react to that?

JS: A day or two, we heard our minister of defense, Lieberman, warning his colleagues that we shouldn’t mess with Trump who was now issuing warnings against annexing territory. It seems he doesn’t care that much about what’s going on in Israel and he doesn’t want Israel to give him additional headaches. So now there’s some disillusionment among the right wing with Trump. I personally didn’t have any hopes for Trump – I never thought he was a great friend of Israel.

CM: Did you see the film The Gatekeepers (2012) about the leaders of the Shin Bet (the Israeli internal security force)? I found it fascinating that all of those leaders felt that every Israeli political leader, with perhaps the exception of Yitzhak Rabin, had tactics but no strategy, no overall vision of what a solution in Israel would be. What’s your feeling about that?

JS: It was very interesting to me, and somewhat shocking, since these people are so knowledgeable about these political leaders. In another sense I was not surprised. Ben Gurion had a vision and followed certain principles. You could be for or against him but you knew what he wanted to achieve. Though I didn’t agree with him, Begin had a certain vision. At a certain point, Rabin developed a vision about peace. It is in our vital interest to achieve a comprehensive peace with those Arab states that are fairly stable – Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia. It is clear that the key to this is a comprehensive peace with the Palestinians through a two state solution. And it’s just right for them to have a state of their own.

CM: I was curious about your polydrama.

JS: We started it in Vienna. It was a big success – it ran for about 20 years. We also played it in Venice, Lisbon, Berlin, Prague, LA and Jerusalem. The idea is to take a certain theme, break it up into multiple scenes and play them somewhat simulaneously so every attendee can navigate or surf at the event.

CM: It sounds like what Diane Paulus (Artistic Director of the American Repertory Theater) did with Sleep No More (2009) in Boston. I also wanted to ask you about Alma Mahler – what was your interest there?

JS: It began with my interest in Gustav Mahler. I read a lot about him and then she stole my interest.

CM: You know the Tom Lehrer song?

JS: Yes. What interested me with her is that she’s a forerunner of a certain type of liberation of women. But she’s not always revered by them because of her many affairs. She did however break the conventions of the time.

CM: You took a philosophy degree at the Sorbonne. What interested you and how did you move from philosophy to theater?

JS: I was interested in French existentialism at the time – Camus, Sartre. I then became very interested in Spinoza.

CM: What aspect of Spinoza?

JS: Mainly his Ethics. I was inspired by his idea that each person perceives the supreme power according to one’s capacities in one’s own particular way. I also was fascinated by his way of reading the Bible, which was revelatory to me at the time.

CM: How did you get from that to the theater?

JS: I had an inclination to dramatic arts but what made the difference was reading Samuel Beckett who attracted me strongly to the theater. He was an artist who found a way to bring philosophical issues to the stage.

CM: Beckett brings a kind of metaphysics to the stage. Your approach seems less metaphysical and more ethical. Did you find a metaphysical basis for your ethical pursuits in Beckett? Is that was drew you to Spinoza?

JS: Perhaps so. And maybe something about humility. At the end of the Ethics, Spinoza identifies happiness as freedom of the spirit and says how very difficult it is to achieve. Otherwise why don’t so many reach it?

A feature article about Joshua Sobol’s residency in Boston by Charles Munitz (aka BADMan) appears in the current week’s issue of The Jewish Journal.

Great interview and sadly in tune with our current political reality. I so value your inquiring mind,Charlie.