Play (1879)

by Henrik Ibsen

Adapted by Bryony Lavery

Directed by Melia Bensussen

Huntington Theatre Company

Boston University Theater

Symphony Hall area

January 6 – February 5, 2017

Scenic Design: James Noone; Costume Design: Michael Krass; Lighting Design: Dan Kotlowitz; Sound Design and Original Music: Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen

With Andrea Syglowski (Nora); Kekou Laidlow (Torvald), Marinda Anderson (Mrs. Linde), Adrianne Krstansky (Anne-Marie), Jeremy Webb (Dr. Rank), Nael Nacer (Krogstad), Lizzie Milanovich (Helene)

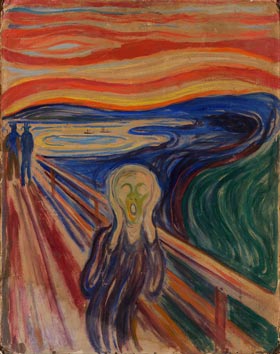

“The Scream” (1893)

Munch Museum, Oslo, Norway

The power and intrigue of this production of the Ibsen classic derives from several sources: the pure vernacular of its translation, the capacity of its director and cast to weave the net of its tragedy elegantly and straightforwardly, and the ingenious abstractness of its set.

Additional curiosity and richness derives from the casting, which is multicultural: Sekou Laidlow (Torvald) and Marinda Anderson (Mrs. Linde) are black. This adds curious overtones, and some significant additional questions about the implications of these casting choices, particularly to the relationship between the imperious Torvald and his wife Nora (Andrea Syglowski).

Kekou Laidlow as Torvald

in “A Doll’s House”

Photo: T. Charles Erickson

Courtesy of Huntington Theatre Company

The knotty and cleverly strangulating setup involves relatively simple parameters. Nora, the amiable, but hyper and indulgent, wife of Torvald, a banker, has spent a lot of money without caution. She has managed to secure a loan to support this by borrowing from the bank with which Torvald has become recently associated, through a bank associate, Krogstad (Nael Nacer), whose job is now threatened. Nora’s transaction has, it turns out, some irregularities, of which Krogstad is aware, and he appeals to Nora to assist him in influencing Torvald to help him retain his job.

Meanwhile, Nora is closely attended by Dr. Rank (Jeremy Webb), a wealthy friend, who would seem to be in a position to bail her out of any financial difficulty, but with an implicit return of affection attached to the bargain.

Approached by Nora regarding Krogstad’s impending dismissal, Torvald seems resolute and unshakeablly determined to let him go, forcing Nora to consider ultimate solutions with more serious and self-destructive implications.

Anyone who has read or has seen A Doll’s House knows that the ending which emerges from this inescapable net of interlocking conditions is curiously modern and unexpected. In some ways that ending is revolutionary and refreshing. Yet, in other ways, it seems inconsistent with the tone and character of what precedes it, discontinuous with and not at all foreshadowed by the intricate and carefully woven plot preceding.

Andrea Syglowski as Nora

in “A Doll’s House”

Photo: T. Charles Erickson

Courtesy of Huntington Theatre Company

The setup of the play is remarkably ingenious. As with all great tragedies, it puts its protagonist in an untenable position, one that grows out of unforeseen and seemingly innocuous preconditions. The sophistication of Ibsen’s capacity to tighten the noose, even in this outwardly tame domestic setting, is distinctive and remarkable. How a bank loan, a spendthrift wife, and an overly self-assured husband, with a couple of troublemakers lingering on the sidelines, can create great tragedy is what make the playwright’s inventiveness so distinctive here.

Were that to follow through clearly and seamlessly into the ending, this already great modern tragedy would have been even greater. As it is, we get an amazingly well-crafted preamble and an ending which, though daring and memorable, does not quite follow from its delicately crafted setup.

That said, one must take strong note of the powerful stage design of this production which, wordlessly, provides a compensation for what Ibsen’s ending promises but does not quite offer.

In the background of the simple but elegant architectural set is a deeply hued interpretation of a motif that one most closely associates with the sky of the iconic painting The Scream by Ibsen’s fellow Norwegian, Edvard Munch. That motif, in addition to being deeply colored, rhythmic and suggestive of the various layers of interaction in the tragedy, also clearly evokes the title and import of the work from which it’s taken.

As the final scene draws to a close, the architectural set parts and leaves that redolent echo of Munch’s motif resonating, as though what had just occurred in the tragedy were The Scream itself. It’s a brilliant, nonverbal support for the somewhat discontinuous and dramatically unexpected ending of A Doll’s House, but serves, perhaps better than any other directorial gesture might, how Nora’s final response is so deeply akin to the spirit of Munch’s painting.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply