Interview

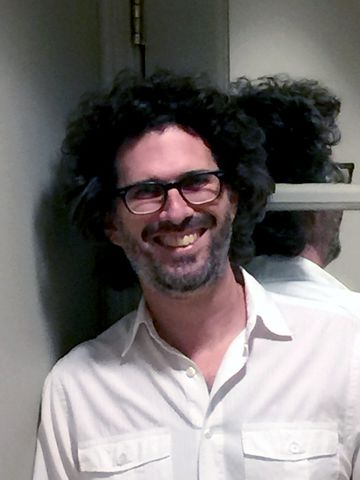

Joshua Marston

Writer/Director of the film Complete Unknown,

scheduled to open in Boston on September 2, 2016.

by Charles Munitz (aka BADMan)

Photo: Charles Munitz

Boston Arts Diary

The following is based on an interview I did with director Joshua Marston in Boston in August 2016 while he was in town in anticipation of the release of his new film, Complete Unknown, about a woman who has adopted a life of shifting identities, starring Rachel Weisz, Michael Shannon, Kathy Bates, Danny Glover and Azita Ghanizada.

Marston is perhaps best known for his celebrated 2004 film Maria Full of Grace about a pregnant drug mule from Colombia.

CM: Complete Unknown is an intriguing film. What got you to take on this story? Was it interest in a particular character or person, or was it thematic? Did you have questions about the nature of identity and come to it that way?

JM: Thematic. I started off being interested in the idea of a character who is not who she seems to be. The idea of changing identity is interesting. And, personally, the idea of going off and being someone else – I fantasize about it! Apart from enjoying filmmaking, there are a million other things that would be cool to do. So there’s always that allure of being able to change who I am as a person, what I do and what world I’m in, going to the opposite end of the world and engaging in some other profession. It’s a gratifying fantasy to imagine a character who does that.

CM: A lot of people change what they do at times of midlife crises, and such.

JM: This takes it to an extreme. What if you didn’t just change your job but you actually changed your name and your whole backstory? And what if, instead of having to put in all the years in order to get to a certain place professionally, you could just parachute into another life?

CM: So instead of training as a surgeon or a nurse, your protagonist just creates a diploma for herself and speaks convincingly about what she’s done.

JM: The character is intended to be a polymath who is so good and so smart and able to move between worlds so easily that she’s a very quick autodidact who can figure enough out in a short time to enable her to literally drop into another life.

CM: But it’s more than just a kind of impatience that drives her. There’s also something weird and interesting about your portrayal – for someone who’s got an apparent pathology she appears quite normal in many ways, strikingly normal. What’s your interest in putting those two things together?

JM: I’m not interested in making a story about someone who’s nuts. She’s not crazy. I don’t want the viewer to so easily dismiss what she does. I’m interested in provoking the questions Is it possible to do what she does? What would it be like to do what she does? Why don’t we do what she does? People go around complaining about their lives all the time without being able to make a change. It’s one of the most difficult things, to make a profound change in your life. So sometimes we tell ourselves stories about how it’s not possible to change – wherever you go there you are – and one of the intentions of this movie is to put that idea to the test. Is it true that we can’t change or is it something we just tell ourselves to make ourselves feel better about not changing? If she were nutso, it would be too easy to dismiss who she is and what she does. I’m trying actually to make it seem possible.

CM: There’s a really nice way in which the enveloping drama about Tom and his wife Ramina have an issue about moving to L.A. so she can attend jewelry school is developed, and you do a good job of showing in the party scene how Tom inadvertently demonstrates how stuck he is with where he is and what he’s doing. The encounter with Alice (the morphing character, played by Rachel Weisz) has the effect of uprooting him enough from his routine to consider the possibilities.

JM: In the same way I don’t want the viewer to dismiss her as crazy, I don’t want the viewer to categorize him as miserable and completely stuck. One of the key things Tom’s character says is that he almost gets nothing from what he does – almost – which, in some ways, is worse than nothing. If you truly get totally nothing, it’s easier to change than if you’re only modestly satisfied. You’re tempted, in that case of being somewhat satisfied, to think you might move to a next level or that something will open up, which makes it harder to walk away from what you have. That feels like a very commonly real situation.

CM: A little satisfaction is a dangerous thing.

JM: Exactly.

CM: Piradello’s novel The Death and Life of Mattia Pascal which is about a guy who leaves his clothes on the beach one day, giving the illusion that he’s drowned, and then goes off and lives his life freely. The wonderful memoir by Geoffrey Wolff, The Duke of Deception, is about his father, who created a whole illusion about who he was. It’s not always clear in such narratives why these characters do what they do. In Complete Unknown what causes your protagonist such distress that she’s forced to entirely abandon her life? At some points it seems that you suggest it’s a bit like an addiction, but don’t seem to commit to that thesis. It’s as though you intentionally didn’t give enough background to justify her actions.

JM: In preparing the story, we developed all of the background material though much of it does not show up in the film itself. We had the full backstory and the character’s psychology outlined. There were moments when there was more of that in the screenplay, but I found that putting more in made the story less satisfying because you walked away feeling like you understood her fully. And that kind of explanation seemed too pat, too explainable, too understandable. I do intentionally give very specific clues about what happened to the character, but if I were to explain it all it wouldn’t leave you wondering. Instead I want the audience to continue to think and to wonder. I’m not intentionally trying to frustrate the audience, just to engage them, to help them be curious. Additionally, it’s important to remember, as explanation, that a lot of the backstory, alluded to concisely but significantly, is in this character’s having been a piano prodigy early on and that she had seen her life laid out doing one thing. Later she says the trap is when people think they know you and lay claim to you, which is very much what had happened to her in her youth.

CM: Have you seen The Music of Strangers (2016), the documentary about Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble? It reveals something interesting about Ma, who is such an open and honest guy and talks very directly about coming into his prominence as a world-class cellist without feeling that actually he had chosen that path.

JM: That’s very much of what we talked about in preparing the character for this film. Every time she develops a new persona it’s a function of feeling the need to be in the driver’s seat, to control and to decide who she is because she had never been able to do that as a young child.

CM: Why couldn’t this character have done that without escaping from the life she had known? Are you creating a kind of cinematic poem here that is not meant to be particularly realistic?

JM: It’s interesting to take something fantastical and relay it as though it were real in order to lead the viewer to go along with the thought experiment, to actively imagine what it’s about. I’m not necessarily asking the viewer to do what Alice does, but at least to think about making some small change in one’s life.

CM: Is there something personal in this?

JM: Yes, it’s very personal, because I have fantasies about doing a million different things with my life, as a lot of people do. There’s a tension between sticking with something until one does it well and then getting bored. But filmmaking is a really good endeavor for someone who feels that to some degree since each new film demands delving into totally different worlds. This film is an extreme articulation, in some sense, of what I’m doing with my filmmaking.

CM: A liberating thought experiment.

JM: Exactly.

Leave a Reply