Film (2016)

Directed by Stephen Frears

Screenplay by Nicholas Martin

With Meryl Streep (Florence Foster Jenkins), Hugh Grant (St Clair Bayfield), Simon Helberg (Cosmé McMoon), Rebecca Ferguson (Kathleen)

Meryl Streep is, as we well know, a wonder. It is hard to find a film that she’s in, however bad, that one doesn’t want to watch. The absolute proof of this was Mamma Mia (2008), a film so dreadful that one would have been hard pressed to stay in one’s seat were not Streep in it and seeming to have such a good time.

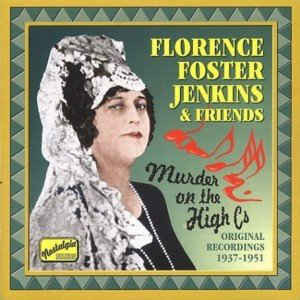

Florence Foster Jenkins is actually a very good film and features Streep (Florence Foster Jenkins) in the title role as a society lady whose singing voice is horrible but who does not realize it. She is rich and is able to rent out Carnegie Hall for a recital and somehow manages to carry it off by the pure power of her optimism and acute capacity for self-deception.

Hugh Grant as St. Clair Bayfield

in “Florence Foster Jenkins”

Photo: Nick Wall

© 2016 Paramount Pictures. All Rights Reserved.

The barometer of Jenkins’ dedication and charm is Cosmé McMoon (Simon Helberg), the pianist she hires to come along for the ride. Helberg is a great comic actor; he played Rabbi Scott in the Coen brothers’ masterful A Serious Man (2009) and pulled off that touchingly funny part with a sweet whimsicality that made for genuine, though subtle, humor. He does the same thing here in the role of the musician horrified at Jenkins’ incapacities but gradually taken with her personhood. Bugeyed and finicky, he comes onto the Jenkins project with ambition and earnestness, only to find out quite soon afterwards exactly how horribly Jenkins sings. Nonetheless, he sticks with her – duly, ably, devotedly.

Jenkins, along with her common law husband, St. Clair Bayfield (Hugh Grant), the perfect accomplice and foil for her romantic self-deception, carries McMoon along until he can resist no longer. As she presses her case to the public, despite its obvious recognition of her musical inadequacies, McMoon warms to her and to the project. He sees that musical quality, in the long run, is less of an issue that the power of personality.

As well, the relationship between Bayfield and Jenkins is complex and touching.

Grant hasn’t put in such a good performance in many years. In the early days, he cornered the market on a self-effacing variant of sexy charm that sold in spades, through such great outings as Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) and Notting Hill (1999). But that eventually wore off and somehow his aging charm has not quite made the hit parade in the same way in recent years. But here it really does, and through a more mature and savvy form of sweetness he shows what supportive companionship in a complex relationship of an aging couple can be about. Streep and Grant make a great pair, so much so that one truly hopes they might test their artistic partnership elsewhere.

Streep is not to be believed in this role. She sings so perfectly awfully, but with charming vulnerability, and she gives the quality of incapacity to be aware of her frailties such believable persuasiveness, giving a vivid sense of how Jenkins, despite her musical liabilities, became such a celebrity.

And a celebrity she was. Apparently, her recording, though unbelievably bad, was a best seller. The recording is a musical equivalent to the cinematic disaster exhibited in the notorious Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959), frequently regarded as one of the worst films ever made, but a cult classic because of its very awfulness. One might argue that the prevailing reason for that was a kind of aesthetic ridicule and sadism that involved a desire to scorn the obvious failings of the music. But there is more to the Jenkins story, as Streep’s performance demonstrates. An unremitting belief in oneself, despite the odds and despite the appearances, has a persuasive charm. There is power in dedication and the incapacity to hear one’s flaws in someone so genuinely naive and psychologically vulnerable. And that, as well, may be why the recording, and Jenkins example, are so popular and in some ways, despite the hilarious awfulness, so compelling.

So, while the film is very funny in one sense it is also quite touching. Seeing the deftness with which the trio – Jenkins, Bayfield, McMoon – support and dance with one another around the prospects of self-delusion and collective support despite that is a lesson in compassion, about truth-telling, about lying, both to oneself and to others, and how that enters ultimately into the cultivation of virtue and integrity.

As an account of dedication and love, in its own strange varieties, the film is, as well as being hilarious, persuasively moving.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply