Play (2009)

by Mark St. Germain

Suggested by The Question of God by Dr. Armand M. Nicholi, Jr.

Directed by Jim Petosa

New Repertory Theater

Arsenal Center for the Arts, Watertown, MA

April 30 – May 22, 2016

Scenic Design by Cristina Todesco; Lighting Design: Scott Pinkney; Costume Design: Molly Trainer; Sound Design: David Remedios

With Shelley Bolman (C.S. Lewis), Joel Colodner (Sigmund Freud)

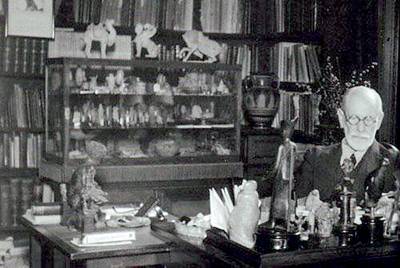

Joel Colodner as Sigmund Freud

in “Freud’s Last Session”

Photo by Andrew Brilliant / Brilliant Pictures

Courtesy of New Repertory Theater

It never happened, but this play imagines what it might have been like if Freud (Joel Colodner), now living in London in the late 1930s to escape the Nazis, invited C.S. Lewis (Shelley Bolman) in for a session. The dialogue pits Freud, an ardent humanist, skeptic and atheist against Lewis, a novelist, an essayist, a talented intellectual and a devout Christian. Pervading the interchange are radio broadcasts signaling the beginnings of the Second World War and attention to Freud’s mouth cancer which cause him considerable discomfort at this point near the end of his life.

The two actors who carry this show, Joel Colodner and Shelley Bolman, are excellent and give vivid and evocative accounts of the two characters they are meant to portray.

Colodner’s Freud is relentlessly nudgy and irritable, as one might well have imagined him to be. Not only has he been displaced from his home in Vienna by the Nazis, but he watches as even England, to which he has fled, is being targeted by them. As the world collapses around him, his already significant sensitivity to false piety, in all sorts of realms, becomes even more vivid and pronounced. As well, as mouth cancer afflicts him in a relentlessly immediate way, so vividly condemning that orifice so vitally connected with the practice of psychoanalysis to constant discomfort, any form of saccharine religious appeasement strikes him, even more so, as completely misguided.

Along comes C.S. Lewis, author of, among other things, The Chronicles of Narnia, a largely Christian allegory, The Screwtape Letters, a fantasized dialogue between two demonic figures in quest of a human soul, and numerous other tracts on faith, to declare his honest affection for and belief in God. Lewis is neither an inarticulate believer nor stiff-necked, which makes him a sophisticated counterpart to Freud. He is well-spoken, sincere, and, in this interpretation, a very decent sort of fellow.

The performances are indeed very good and give a window into the lives and characters of these two very different luminaries. Oddly, the play itself, though an interesting exploration of this imagined encounter, feels like a pitting of two different philosophical positions against one another rather than a more complex and nuanced exploration of an interplay between characters and personalities. The obvious differences between the irascible, sarcastic and very ill Freud and the very British and composed Lewis become obvious and there are some other allusions to aspects of family and sexuality that do embellish their contours, but there is not an excessive amount of modeling of their respective characters in a way that might make them feel more vividly real.

There is an interchange in which Freud asks Lewis about his housemates, among them his brother, suggesting it as somewhat odd for grown men of the time, and Lewis returns the favor by asking Freud about his overly devoted relationship with his daughter Anna, neither suggesting anything salacious on either end but strangely wrought familial connections as revelatory of the personality of the other.

There is a bit more to the interchange than pitting the nonreligious Freud against the religious Lewis, but not a great deal more. In the end, it does feel like the two characters have been called in to have a debate about God rather than to explore something potentially more personally interesting.

In Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen, a real but not well documented historical encounter between Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg during World War II serves as the impetus for a dramatic extrapolation of what might happened between them. Because of the heavy consequences – the development of an atomic bomb – the stakes for are high and the drama provides deeply structured layers of intrigue.

In Freud’s Last Session, the fictional encounter does not have any such real consequences. We know that the war is about to begin and Freud is about to die, but other than that there’s no particular reason to feel invested in this encounter. That playwright Mark St. Germain has created it provides a moment of intellectual improvisation which is interesting but not urgent. With, however, the caliber of performances that Colodner and Bolman offer, that indulgence provides an opportunity for a beautifully acted duet which is in itself rewarding.

The set by designer Cristina Todesco is outstanding. Modeled on the image of a spiral – inspired by a quote from Lewis highlighted in the program – the stage erupts in a vortex that creates a highly dynamic and suggestive context for the meeting of these two intense intellects.

– BADMan

Charlie–I like the intellectual backstory you added here and the setting for their exploration of God. I’d add, what was for me, the image Lewis tells us of his conversion experience and the immediate means by which that happened. His conversion, of course, is something Freund can neither understand nor tolerate. The other thread through the play is music. It interrupts Freud at points throughout the play and sets him on edge, in part, because he cannot understand, or tolerate it because it accesses a part of him he has not been able to subject to his theorizing brain.