Musical (2015)

Book, Music and Lyrics by Dave Malloy

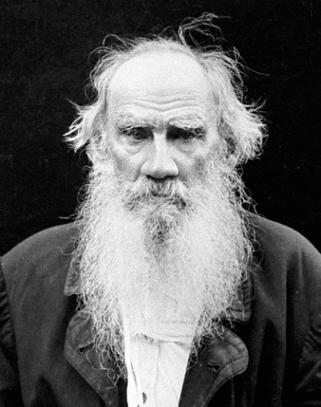

Adapted from War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

Directed by Rachel Chavkin

Choreography by Sam Pinkleton

American Repertory Theater

Cambridge, MA

December 6, 2015 – January 3, 2016

Scenic Design: Mimi Lien; Costume Design: Paloma Young; Lighting Design: Bradley King; Sound Design: Matt Hubbs; Wig and Makeup Design: Rachel Padula Shufelt; Music Supervision Sonny Paladino; Music Direction: Or Matias

With Brittain Ashford (Sonya), Gelsey Bell (Mary), Nicholas Belton (Bolkonsky/Andrey), Denée Benton (Natasha), Nick Choksi (Dolokhov), Lilli Cooper (Hélène), Grace McLean (Marya D), Paul Pinto (Balaga), Scott Stangland (Pierre), Lucas Steele (Anatole), Ensemble: Sumayya Alik, Courtney Bassett, Josh Canfield, Ken Clark, Erica Dorfler, Daniel Emond, Lulu Fall, Ashley Perez Flanagan, Nick Gaswirth, Azudi Onyejekwe, Pearl Rhein, Heath Saunders, Katrina Yaukey, Lauren Zakrin

Lucas Steele as Anatole

in “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812”

Photo: Gretjen Helene

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

The novelistic terrain of what many consider to be the greatest novel of all time is lavish, broad and complex, but can be boiled down to a few essentials, which this great, fun, exotic and exuberant musical does with energy and a kind of rough-edged panache.

Natasha (Denée Benton), the female protagonist, is beautiful and betrothed, to Andrey (Nicholas Belton), who is on the battle front giving his all for the Russians against the French during the Napoleonic Wars of 1805-1812. Though she yearns for Andrey, she is taken in by the handsome and roguish Anatole (Lucas Steele) and her heart is torn.

Voting for her better side and for devotion to Andrey is Sonya (Brittain Ashford), Natasha’s cousin, but she will not be swayed. Meanwhile, Anatole’s brother-in-law, Pierre (Scott Stangland), a schlubby Count unhappily married to Hélène, tries to make sense of his own life, which comes into some focus when he is finally confronted by Natasha’s confrontation with the errant complexities of love.

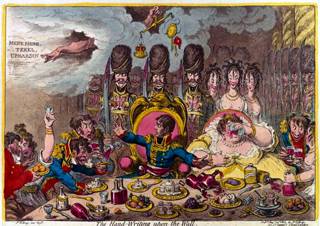

“The Handwriting Upon The Wall” (1803)

The American Repertory Theater under Diane Paulus has, over the past number of years, made bold attempts to bring serious works to audiences in new and fun ways.

Her early seasons were marked by an attempt to do that with Shakespeare. Sleep No More (2009) was an extremely popular fun-house version of some combination of Macbeth and Hitchcock-like suspense which allowed audiences to witness the core of the drama by wandering from room to room. Other enterprises involved a bluesy musical adaptation of The Winter’s Tale.

A couple of years later, Paulus and the ART attempted to entertainingly convey something about Schubert’s life and famous song-cycle Winterreise through the delights and antics of Three Pianos, which indeed featured three pianos onstage, with a lively cabaret atmosphere embellished by the serving of wine to audience members during the performance.

in “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812”

Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

The current outing is a great continuation of that tradition with its rockified version of War and Peace. It’s totally electric in its approach – full of energy, pizzazz and attitude – and it keeps the audience going full tilt for the full duration of its two and a half hours.

Lo and behold, the current outing is written by the very same Dave Malloy who wrote that enthralling Three Pianos and is directed by the very same Rachel Chavkin who directed that exuberant Schubert-fest.

Set up like a combination of opera and cabaret, the action goes on principally in a three ring setup midstage, but, as well, all around the theater. Platforms erupt in the middle of a row of seats and one looks up and sees some actor parading there, playing the guitar or even doing the kazatsky.

Audience intimacy is way up there in this production, and in several numbers the main actors sit themselves down right in the middle of a group of audience members situated in one of the three principal rings.

in “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812”

Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

The Loeb Theater at Harvard has been reconstructed signficantly for this production, with seats rising on both sides of the central stage and with brass railings, much like the opera, installed at every turn. Starburst chandeliers, very reminiscent of those at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, are arrayed from the ceiling, and, at the very end of the show, when the theme of the comet takes precedence, they dim against the dark heavens as starlights.

Opera is an explicit theme early on in the show when Natasha attends the opera and encounters Anatole, but it actually represents a more central motif throughout. This show is itself a variant of opera with virtually no spoken dialogue – everything is sung. Though the narrative, as well, has a romanticized quality akin to that which informs many great nineteenth century operas, there is also something rougher and readier about the production, more postmodern. It is at once vividly colorful and surrounded by bleakness, suggested both by the ingeniously and colorfully designed costumes, and by the austere draping of the walls and ceiling in the entrance and lobby. This is post-Romantic romanticism which is forced to confront vacancy and totalitarianism with screams with of color and swaths of sound.

in “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812”

Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

The entry to the theater indeed seems like a Christo installation. The entire lobby and entryway in the Loeb are roughly covered with plastic sheeting, with political posters slapped on roughly erected plywood panels around the sides. Warnings of the liberal use of strobe lights are posted along with La Lutte Continue (The Struggle Continues) posters and images of rockets or missiles shaped in the form of lipsticks. In effect, we enter the world of nineteenth century Russian romanticism through the entryway of twenty-first century political bleakness.

in “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812”

Photo: Gretjen Helene

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

The music rips throughout, with a fascinating instrumentation peppered throughout the various stage areas. Two cellos and a viola sit high on the back stage, while the conductor, who also plays the piano sits in the middle ring with a bassist. Violinists, guitarists, accordion players all wander around the stage, while a drummer is hidden in the wings and a clarinetist sits off to the side.

The lyrics are intentially ordinary. There’s a vernacular quality to all of them, without poetizing, that adds a kind of recitative down-to-earthness. It’s about as far from the ingenuity of Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter or Stephen Sondheim as one could imagine. It is a bit like the hit musical Rent (1994) by Jonathan Larson in this way, defining its simple language directly, defending itself with a persistent charm that prevails throughout.

Singing and dancing are exuberant and frequently distinctive.

Denée Benton as Natasha has a lovely lyrical Broadway voice, and Lucas Steele as Anatole has a clear, striking hyper-tenor that hits some really high notes for a really long time. Brittain Ashford as Sonya is perfectly appealing while sounding like a folkie chanteuse like Carole King. and Lilli Cooper as Hélène has a bluesy depth that really swings. Nicholas Belton has a great, funny turn as the crazy older Bolkonsky.

Offering the existential ballast of the show is Scott Stangland as Pierre, who does quite a creditable job of conveying the sense of an alienated fatalist who hovers on the edge of realization.

The staging is done impeccably well, with unbelievably coordinated lighting and movement that occurs with precision all over the theater. The overall effect is very exciting and stimulating.

As forewarned, there is an elongated stretch with an enormous amount of strobe lighting, which some may find daunting and overwhelming. The imposition of that technique feels right in line with the lobby decor, a testament to the overwhelming of culture by political and psychological tyranny. Whatever the conveyed signficance of the downpour of strobe lights, it can be a lot to sit through, a bit more suited to an intense punk show than to a more popular, slightly punkified, rock opera headed straight for Broadway.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply