Film (2015)

Documentary

in English and French with subtitles

1 hr 19 min

Directed by Kent Jones

Screenplay by Kent Jones and Serge Toubiana

Film Editing by Rachel Reichman

Music by Jeremiah Bornfield

Kendall Square Cinema, Cambridge, MA

With Alfred Hitchcock, François Truffaut, Martin Scorsese, David Fincher, Wes Anderson, Richard Linklater, Olivier Assayas, Peter Bogdanovich, Arnaud Desplechin, James Gray, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Paul Schrader

François Truffaut

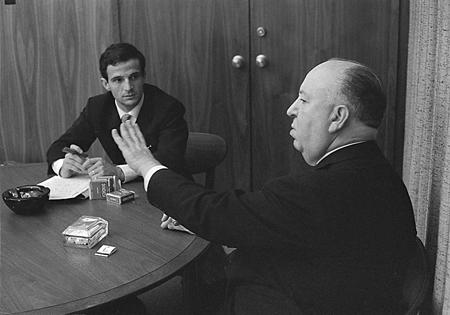

Photo: Phillippe Halsman

In 1962, the young French film director, François Truffaut, in his thirties but with a several significant films under his belt (The 400 Blows, Jules et Jim), wrote the great Alfred Hitchcock, then in his mid-sixties, to express his admiration and to ask him if he might consider engaging in a series of interviews. Moved to tears by the sincerity and intensity of Truffaut’s tribute and appeal, Hitchcock agreed to the project. Truffaut went to to Universal Studios in Hollywood with a translator, engaging with Hitchcock over the span of a week. The sessions were taped, and four years later Truffaut published a written account of them.

Original Edition (1967)

The result was a classic text, published in France in 1966 and in the United States a year later, then and now widely revered by film practitioners and devotees. It’s an analysis, title by title, of Hitchcock’s films, treated through that series of interviews.

The current documentary uses that project as a way of bringing this remarkable collaboration to life and to giving a sense of the effect of Hitchcock’s artistic contribution on some of the great filmmakers working today.

Apparently, it packs so much substantial film wisdom into it that it is treated almost like a Bible by some of them.

Director Wes Anderson (The Royal Tenenbaums,The Grand Budapest Hotel) says his copy is so worked through that it’s deteriorated into a stack of papers with a rubber band around it.

Director Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, The Wolf of Wall Street) expresses great appreciation for the liberating effect of that work on himself and other young filmmakers of his generation: “It’s as though someone took a weight off our shoulders and said you can do this, you can go,” he recalls.

Alfred Hitchcock

A good amount of audio from those recorded interviews makes its way into this delightful and informative film, as does a fair amount of historical film footage, including informal shots of Hitchcock as a young man.

Hitchcock began his work life as an engineer and moved on to advertising, production design and scriptwriting. At one point, he was asked: How would you like to direct a picture? His response was: I’d never thought about it. I was 23. He did give it a try, and the rest is film history.

Even very early on, in the film The Lodger (1927), David Fincher (Gone Girl, The Social Network) notes that Hitchcock’s inventiveness and style were apparent. He was, according to Fincher, “playing with all those things that make cinema fun and magic.”

Anderson corroborates Fincher’s general view about Hitchcock, accentuating his inventiveness and individuality: “This is someone whose mind is full of ideas and this is why we refer to him all the time.” As well, Anderson is struck by how Hitchcock’s visuals are “so graphic and precise.”

– Wes Anderson

Director Richard Linklater (Boyhood, Before Midnight) remarks about how successfully Hitchcock cultivated the purely visual techniques of the silent era observing that “so many of Hitchcock’s (sound) films themselves work as silent pictures.” As well, Linklater recognizes Hitchcock’s “incredible confidence in every shot.”

In addition to serious treatments of multiple Hitchcock films, there are extended analyses of Vertigo (1958) and Psycho (1960). Director Peter Bogdonovitch (The Last Picture Show) remembers never having heard an audience shriek like it did at the climax of Psycho. Scorsese elaborates on what he regards as the cinematic poetry of Vertigo, a film which he feels has just enough plot to “hang things on.”

by François Truffaut”

Revised edition (1985)

When Truffaut’s book was published in 1966, his own career was beginning to really blossom, and he continued to direct at least one film, sometimes two, per year. Hitchcock had only three more films in him. The two remained lifelong friends. Hitchcock died in 1980 at the age of eighty. Truffaut, tragically and unexpectedly, died four years later at the age of fifty-two, felled by a stroke and subsequently diagnosed with a brain tumor. A revised edition of the classic book came out in 1985.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply