Film (2014)

Directed by Giulio Ricciarelli

Screenplay by Giulio Ricciarelli and Elizabeth Bartel

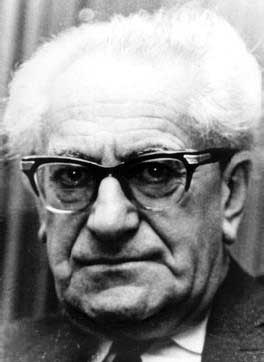

With Gert Voss (Fritz Bauer), Alexander Fehling (Johann Radmann), Andre Szymanski (thomas Gnielka), Friederike Becht (Marlene), Johannes Krisch (Simon Kirsch), Hansi Jochmann (Erika Schmitt), Johann Von Vulow (Otto Haller), Robert Hunger-Buhler (Walter Friedberg), Lukas Miko (Hermann Langbein)

in “Labyrinth of Lies”

Photo: Heike Ullrich

Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

In 1963, well after the Nuremberg Trials, and even after Eichmann’s trail in Jerusalem in 1961, a series of court cases, now referred to as the “Frankfurt Auschwitz” trials, took place in Germany. Directed towards ex-Nazis who had who had significant roles at Auschwitz and were still living in Germany, these prosecutions served to bring to the attention of the German public revelations about the atrocities that had either been unrecognized or suppressed.

Labyrinth of Lies, a 2014 film directed by Giulio Ricciarelli, traces this story from the perspective of a young prosecutor, Johann Radmann (Alexander Fehling), who becomes the motivating force behind the investigations. Following his evolution from a prosecutor in traffic court to the lead of a major investigation of surviving perpetrators of Nazi crimes at Auschwitz, this moving film, inspired by history but dramatically embellished, seeks to symbolically trace the early development of Germany’s coming to terms with its horrific past.

Alerted about a school teacher whom a Jewish survivor of Auschwitz encounters and recognizes as a Nazi who had been there, Radmann gets assigned to a department under the supervision of the district attorney in Frankfurt, Fritz Bauer (celebrated German actor Gert Voss, in his last film role), and, with a small dedicated cohort, pursues an investigation that expands beyond its initial boundaries towards capturing Eichmann and Mengele. Bauer introduces Radmann to Israeli “journalists” interested in the case – actually Mossad agents – making the international case more complicated. The political motivations get more subtle and intricate as Eichmann is essentially delivered to the Israelis.

in “Labyrinth of Lies”

Photo: Heike Ullrich

Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

A love story involving the noble and idealistic Radmann and a beautiful seamstress, Marlene Wondrak (Friederike Becht), enlivens the action, adding further complication and dimension to it as well, as their own familial stories unwind.

The only trouble is that the film is historical in some aspects, not in others, and some of its emphases don’t quite do justice to the balance of the history.

Though Radmann’s character is a fictional amalgamation, Fritz Bauer, Radmann’s boss, is actually an historic figure, and an interesting one. A German Jew, he was a judge in Germany in the 1930s, then, after organizing an anti-Nazi general strike with other Social Democrats in 1933 in Stuttgart, was briefly imprisoned in the Heuberg concentration camp before being released. Fleeing to Denmark and then Sweden, where he spent the war, he returned to Germany and served in a variety of governmental positions including the one as district attorney in Frankfurt as depicted in the film. As a German Jew returning home after the war, and as a Nazi hunter, he remained a stranger in a strange land. He was also homosexual, further alienating him from the surrounding culture. He died in Frankfurt in 1968.

Contrary to the emphasis of the film which conveys the impression that Radmann is the driving force behind the investigations that lead to the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, it turns out that that, historically, Bauer was the actual driving force, though there were, indeed, several young, non-Jewish German prosecutors – on whom the character of Johann Radmann is based – who played focal roles in the inquest and subsequent trial.

It was, as the film suggests, Bauer who actually contacted the Mossad with information about Eichmann that directly led to his capture by the Israelis. (Apparently Bauer intentionally allowed the Mossad to steal files from his office.) Though the potency of the moral drama of the young and determined German prosecutor is very much to the point and dramatically penetrating, the real historical background of the Frankfurt Auschwitz investigations in which the Jewish Bauer was the motivating force gets somewhat overshadowed.

Instead, the focus on the young German prosecutor and his girlfriend gives dramatic potency to the issue about their parents’ generation’s relationship to Nazism and their own generation’s mixture of attitudes towards uncovering and coming to term with that. Near the end of the film, Radmann and another young German make a pilgrimage to Auschwitz and say the Kaddish together from a prayer book lent by a Jewish friend. It’s melodramatic, certainly not in keeping with ritual guidelines, but very moving nonetheless.

Overall, the film is beautifully shot and edited and written in such a way to convey the passionate intent and moral fiber of its protagonist. It is a sincere attempt to depict the early phases of German moral reflection on its Nazi past. Its title in German, Labyrinth des Schweigens, actually translates to “Labyrinth of Silence,” rather than to “Labyrinth of Lies,” but the sense of silence as depicted in the film suggests an avoidance that feels like a lie.

The film treads on the boundary between history and fiction in a way that does not do total justice to history. Yet, given the recognition that the fictionalized story of the protagonist is an attempt to frame something about camouflaged criminality,collective guilt and the honorable inquiry into it,this well-executed film provides significant satisfactions.

– Originally published as ‘Labyrinth’ Dramatizes Auschwitz Prosecutions by Charles Munitz (aka BADMan) in the

October 23, 2015 edition of The Jewish Advocate.

Leave a Reply