Opera (2015)

Music and Libretto by Matthew Aucoin

World Premiere

Directed by Diane Paulus

Featuring Chamber Orchestra: A Far Cry

Conductor: Matthew Aucoin

Set Designer: Tom Pye; Costume Designer: David Zinn; Lighting Designer: Jennifer Tipton; Choreographer: Jill Johnson

American Repertory Theater

Citi Performing Arts Center Shubert Theatre

Boston

May 29 – June 7, 2015

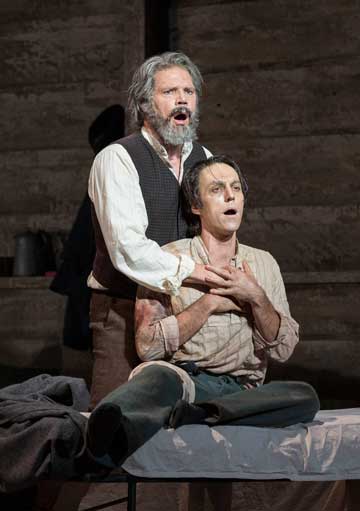

With Rod Gilfry (Walt Whitman), Alexander Lewis (John Wormley), Davone Tines (Freddie Stowers), Jennifer Zetlan (Messenger)

Alexander Lewis as John Wormley

in “Crossing”

Photo: Gretjen Helene Photography

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

Walt Whitman worked as a nurse during the Civil War, prompted into action in a field hospital by getting word of his brother’s wounding at the Battle of Fredricksburg. His brother, it turned out, had suffered a minor facial wound, but Walt stayed on in the hospital for a longer time than expected, so drawn was he to the wounded soldiers and to the work of caring for them.

This superb, relatively short, opera (roughly an hour and forty minutes, played without intermission) conveys, both literally and figuratively, the spirit of Whitman’s engagement with the wounded soldiers, and gives, especially in the work’s coda, an embracing poetic vision that reverberates from that historic setting to the present.

Cast, as one would expect, with almost all men, the piece has a bit of the feel of Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd (1951), which takes place at sea on a British naval vessel. There are, in Crossing, a couple of female parts – one figuring choreographically in a dream sequence, the other, the Messenger (Jennifer Zetlan), beautifully evoking the pathos of the reportage of the end of the war given in the coda – but there is a dominantly male energy to the piece.

Musically, as well, the opera calls to mind something about Billy Budd and Britten’s style of composition. With a prevailing minimalist but lyrical temper, Aucoin creates an elaborate series of textures that weave and fold into one another, erupting from different orchestral corners and continually varying in tonality and shape. Britten wrote as a modernist, not a minimalist, but never allowed the abstractions of modernism to interfere with the lyricism of his writing.

Aucoin seems to prevail upon minimalist in an analogous way. He makes robust use of its idioms – on can hear Philip Glass-like ripples and runs throughout – but never indulges in that motif in a way that overrides the innate impulse to variety. I would not be as inclined to call Crossing quite as lyrical as Billy Budd, though it is indeed beautiful throughout. In this sense, his take on minimalism has a different quality than that of Philip Glass, which has a kind of intoxicating relentlessness to it. Glass’ music is also more varied than it might seem at first blush, but here, in Crossing, Aucoin has managed to create some of the urgency of Glass’ idioms while never allowing that intentional repetitiveness that is the hallmark of Glass’ work to overcome the announcement of tonal variations.

Matthew Aucoin, Composer

“Crossing”

Photo: Jeremy Daniel

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

The result is a very coherent work that truly feels like an opera – grand, expressive and passionate – and which is musically interesting throughout.

The production itself is wonderful. The singing, from top to bottom, is first-rate. The orchestra – the ensemble A Far Cry (love the name!) – under Aucoin’s baton, is precise and powerful. The staging, done by ART artistic director Diane Paulus, is inventive without being unsettling; the disposition of a Civil War hospital prevails, while multimedia and choreographed embellishments surface from time to time to expand the view, but not imposingly.

Rod Gilfry (Walt Whitman) has a convincing presence and warm and pleasant baritone suited well to the role. He conveys the intensity and humanity of the poet both through voice and gesture.

Alexander Lewis (John Wormley) as the wounded soldier who newly arrives in the camp and who carries a big weight on his conscience has a distinctive tenor, plaintive and far-reaching.

Davone Tines (Freddie Stowers) as the African-American soldier who comes, near the end, to help finish the tale, also has an exquisitely evocative tenor.

Jennifer Zetlan (Messenger) as the woman who comes to offer the coda, provides, again, a wonderfully distilled soprano solo that helps sew up the poetic corners of the piece.

There’s something philosophically and musically similar to Philip Glass’ Satyagraha (1979), a poem-narrative about Gandhi and his philosophy, in this piece. Like that powerful, but not narratively traditional, opera, Crossing takes off from an historical set of events, but weaves, in its broader scope, a poetic spread that infuses the historic story. That infusion of poetry into narrative may disrupt some of the expectations for more clearly focused narrative that many opera enthusiasts intuitively anticipate. Yet, those opera enthusiasts who find things like Satyagraha appealing will naturally tune into the poetry-cum-narrative of Crossing and accept its departures from traditional narrative as interesting embellishments rather than as disruptions from the dramatic core.

I would expect this beautifully conceived work to soon find its way into more mainstream American operatic repertoire and spells a significant artistic step for this talented young composer.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply