Play (1949)

by Arthur Miller

Directed by Spiro Veloudos

Lyric Stage Company

Boston, MA

February 14 – March 15, 2014

Scenic Design: Janie E. Howland; Lighting Design: Karen Perlow; Original musical compositions: Dewey Dellay

With Ken Baltin (Willy Loman), Paula Plum (Linda), Joseph Marrella (Happy), Kelby T. Akin (Biff), Victor L. Shopov (Bernard), Eve Passeltiner (The Woman), Larry Coen (Charley), Will McGarrahan (Uncle Ben), Omar Robinson (Howard Wagner), Margarita Martinez (Jenny), Jaime Carrillo (Stanley), Jordan Clark (Miss Forsythe), Amanda Spinella (Letta)

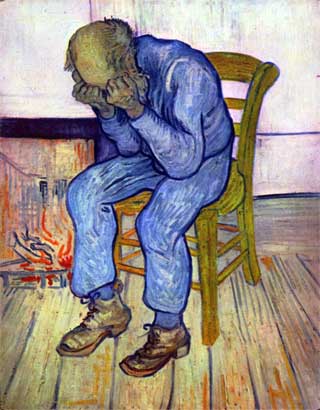

Kröller-Müller Museum

The Netherlands

Death of a Salesman was originally entitled The Inside of His Head and the structure of the play retains that orientation: the collage-like view of memory and present action as intimately interwoven and almost indistinguishable. Salesman shows that stream of consciousness for Willy Loman, an American salesman, who at sixty, loses his grip on work and on hopes for his family.

This is a long play – it runs almost three hours in this production – but it is striking how every minute counts. The structure is episodic and psychological rather than linear, so it never plods along and always provides surprise and insight about the present through Willy’s recaptured meanderings in the past.

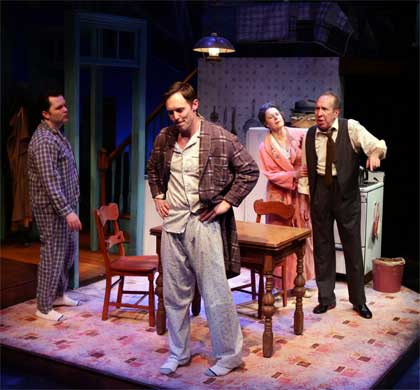

Though I have seen some great productions of Death of a Salesman, Ken Baltin and Paula Plum provide the most heartrending and convincing embodiments of Willy and Linda Loman I have seen.

Paula Plum as Linda, Ken Baltin as Willy

in “Death of a Salesman”

Photo: Mark S. Howard

Courtesy of The Lyric Stage

Baltin’s Loman has a magical combination of desperation, hope, dissipation and energetic ambition. How Baltin manages to weave all of these together to give the sense of a very believable ordinary guy is just amazing. There is no bravado to his interpretation and that makes it all the better. Watching some of the great and notable Willys of the past, I was always somehow aware of them portraying Willy. With Baltin, I get the sense of his embodying Willy with an incredible intimacy and believability. His sewing together all these aspects of Willy’s personality is so adept that one can, at once, see how all the parts – the despair, the miscast ambition for himself and for his sons, the pride and the resistance to accepting things as they are – work together to produce this contemporary tragic protagonist while at the same time drawing one into a deep empathy for him.

Paula Plum’s Linda is equally adept in its subtleties. Though not as dramatically pronounced a role as Willy, Linda has to offer a pervasive sense of support and concern for him while indicating her way of figuring into the tragic amalgam of traits that make the family so desperate. Plum’s Linda is neither a pushover nor a manipulator, and she is sweetly sympathetic without being saccharine. It is a tough role to pull off well and Plum does it subtly and convincingly.

One of the odd parts of Miller’s script is that it is not sociologically specific. Though the play was first produced in 1949 and it seems that some of action is germane to that era, there is virtually no reference to World War II. One presumes that the sons, Biff and Happy, now thirty-four and thirty-two, would have served in the war or that there would have been some indication of its effects upon the family, but there is none.

Nor do we have a sense of what background or ethnicity they are. Loman is a nonspecific name. Though Arthur Miller was Jewish, Willy Loman might or might not be. The name of his uncle – Ben – played here robustly and convincingly by Will McGarrahan – suggests the possibility of Jewish heritage, but that is not at all definitive. On the surface, the names of his sons, Biff and Happy, do not suggest anything in particular about Jewishness, until one discovers, in passing, that Happy is a nickname for Harold, which might be. However one slices it, Miller was writing a play that could not be identified by those ethnic or sociological parameters. On the one hand, it seems like a cagey dodge, but the play is so great that the move makes for a kind of universality which, no doubt, was Miller’s primary intent.

In this production, making Willy’s boss Howard (done with a deftly energetic callousness by Omar Robinson) an African-American is far more in tune with a timeless, sociologically non-realistic approach than with one that fits carefully into the late 1940s.

Ken Baltin as Willy

in “Death of a Salesman”

Photo: Mark S. Howard

Courtesy of The Lyric Stage

As older son, Biff, Kelby T. Akin is quite affecting and becomes more so as the play develops. He does adequately fit the bill of a high school football hero, which the role requires, and which makes his fall from grace that much more desperate.

The set by Janie E. Howland is condensed, but eloquently conceived, with Willy’s and Linda’s bedroom in the shadow of the 1940s kitchen, and Biff’s and Happy’s room hovering above. It works brilliantly well for the compact Lyric Stage theater, and Karen Perlow’s lighting enhances this distinctively. Dewey Dellay’s musical settings add to the embrace and are highly effective.

Again, director Spiro Veloudos has worked a kind of magic at the Lyric. His repertoire is extremely varied, but he seems capable of pulling off tragedies and musicals with equal panache.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply