Poetry Reading

Boston University

Boston, MA

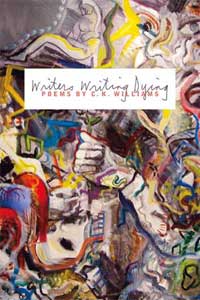

C.K. Williams is in his mid-seventies and has had a fairly recent volume of Collected Poems published. That, however, has not stopped him from writing, and at this reading he mostly recited poems from a new book, Writers Writing Dying. It was delightful.

I have a number of volumes of Williams’ work and have always appreciated him from a bit of a distance. When I have sat down to read his poetry, I have sometimes not quite been able to connect with it. He writes in a style that makes use of uniformly long lines in free verse, the form of which I have not always felt engaged by.

However, in this reading, I gained a new appreciation for Williams’ poetry. Hearing it, and hearing him read it, made it come alive. He reads his poems naturally and straightforwardly, but with great heart. Wave upon wave of images, word gestures and references emerged from the lines, the length of which became sources of only gentle modulation in the reading.

He began with a poem entitled Whacked, which refers to the feeling he has reading all the great poets who he feels brutalize him with their apparently superior capacities. “What a relief to read some bad poems,” the poem responds humorously. The ironic result is Williams’ production of this lovely poem about the pain of reading, and of writing. It ends, appropriately, with images of birth.

The Hundred Bones is set, in part, in World War II, and also calls up images of Basho, the famous Japanese haiku poet. It invokes the notion of “a windswept spirit” that inhabits the body of “a hundred bones;” at the same time the poet says, with alarm and awareness, “the war has found me.” Delightfully, he alludes to a famous haiku of Basho, beautifully picturing the “barely there frog.”

Vile Jelly calls to mind Gloucester’s blinding in Shakespeare’s King Lear and the famous, disgusting line about it, “out out vile jelly!” Ugh. Williams then brings up the issue of reactionary school textbook selection in contemporary Texas casting evolution in a suspicious light, asking “will the eyes of conscience also be punctured?” and putting forth the image of “chopping minds from susceptible eyes.”

Bianca Burning refers to Bruno Schultz, a Polish writer from the 1930s who Williams identifies as one of the great prose stylists of the 20th century. This poem invokes a circus character described by Schultz, who had “breasts too beautiful to remember” and who “struts across the arena with whip, to take her bow.” Riveting.

Mask calls forth Santayana, Hölderlin and Yeats in Wiliams’ attempt to “allow other writers to be there” in his poems. Calling the mask “a disguise to conceal the monster,” it also recalls fear in the movies, noting “it hurt to be frightened.” With new found awareness, he suggests “this time, no covering your eyes.”

Exhaust is a painful poem about suicide which recalls the memory of Anne Sexton, who died a suicide from auto exhaust, and Jackson Pollock, who died in a car crash. It also calls to mind Williams’ several close calls in cars, the death of his grandfather, and the toy cars with which his grandson now plays.

Haste reflects on pacing, and loss. “Not so fast, people were always telling me,” is the advice that leads to a meditation on the loss of the Irish language at the hands of the British in the nineteenth century, and of Yiddish in the twentieth.

Poem for Myself on My Birthday is a funny and heartbreaking poem about getting older, likening a birthday to a charging African animal on a safari. It also humorously calls to mind the Dalai Lama, who, having birthdays as well, “pumps a treadmill like a prayer wheel.”

Photo: Vernon Doucette

The veteran poet Robert Pinksy, who is on the faculty at Boston University, introduced the evening.

Photo: Michael Cuthbert

A younger graduate of the writing program at the university, Eleanor Goodman, read a few of her own poems and introduced Williams. According to the terms of the grant which supports the series of which this reading was a part, a young and recent graduate of the writing program must do this at the reading, a great idea.

Goodman read several of her poems, which were delightful. One of them called to mind the poet’s forebears leaving Nazi occupied Europe, then beautifully morphed to an image of the poet dressed to the nines passing a street person in Harvard Square who looked at her then asked “where are you from?”

She is also a translator of Chinese poets, and read a poem in the original Chinese, and her translation, both wonderful.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply