Concert

Boston Philharmonic Orchestra

Benjamin Zander, Music Director

Sanders Theater

Harvard University

Cambridge, MA

Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Island, Op. 22 No. 1

Prokoviev

Violin Concerto, No. 2 in G minor, Op. 63

Stefan Jackiw, violin

Richard Strauss

Don Quixote, Fantastic Variations on a Theme of Knightly Character, Op. 35

Rafael Popper-Keizer, cello

Lisa Suslowicz, viola

I heard Stefan Jackiw play the Beethoven Violin Concerto with the Boston Philharmonic some years back and was mightily impressed. I think he was a Harvard undergraduate at the time. His tone was rich and full and he was memorably expressive, seeming to sit down into his fiddle and draw out sound like rich taffy.

It is now years later and Jackiw is in his upper twenties (he was born in 1985). He still plays expressively and with beautiful tone and the years have added a dimension of subtlety to his playing.

Photo courtesy

Boston Philharmonic Orchestra

To play the Prokoviev Violin Concerto, No. 2, he came out dressed in silken black pants and shirt, and, almost like a martial arts adept, leaned into the first phrases with lithe grace and intensity. For that beautifully haunting opening theme, Jackiw appeared to almost slither into it. But when, soon after, punctuated phrases arose, he attacked them with superb clarity. He executed the quick and difficult passages masterfully, but when the high, creeping passages came along, he seemed to disappear, tiptoeing almost magically into them.

The orchestra, under Benjamin Zander, rendered the mixture of Prokoviev idioms most adeptly, bringing together passages of heavily-laden, marching columns of notes with those of a signature playfulness.

While delivering the intermediate Andante, Jackiw demonstrated his ability to take every possible dramatic opportunity from the music, exhibiting beautiful gestural phrasing through the semi-tonal wilderness. And, in the quiet passages, he played so delicately it seemed to come from almost nowhere.

The final Allegro exhibits some of the more tortured tonalities from Prokoviev’s toolkit, but still brims full of that omnipresent comic-ironic urge.

The orchestra dutifully brought forth the underlying sounds of mechanism and authority, while the violin cried out with a sense of returning boldness and pride. When called for, the orchestra scrambled through complicated unisons commendably.

As Jackiw called forth Prokoviev’s echoes of the opening theme, he recapitulated, in the closing sequences, the passionate sense with which he approached the entire piece.

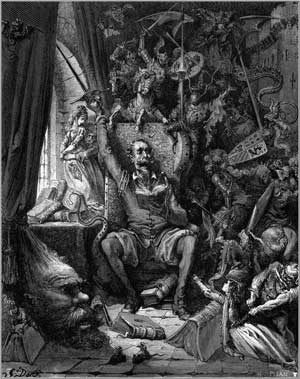

Photo courtesy

Boston Philharmonic Orchestra

Rafael Popper-Keizer is the Philharmonic’s long-time principal cellist. As Benjamin Zander noted in his comments before playing Don Quixote, it was far more commonplace, in a symphonic age gone by, for the principals of string sections to come forth to play virtuoso solos with the orchestra. Occasionally, such pieces require exceptional technical mastery. But, as Zander noted, with warm appreciation, the principal cellist, in this case, was well up to the task of delivering the extremely challenging solo for this Strauss tone poem.

Popper-Keizer did a wonderful job, conveying the part with requisite crispness and lyricism.

The violins opened with playful and whimsical themes, carefully and cogently delivered. A beautiful, lyrical oboe followed upon them, and then the orchestra opened up wide with big, full landscapes of sound, vivid and strong.

In his observations before the piece, Zander helpfully delineated the various parts of the tone poem characterized by nine episodes taken from Cervantes’ classic sandwiched between the opening and closing sequences. Having heard Zander’s explanations and the associated orchestral quotations, it was fun to follow along and try to identify the various programmatic representations.

After the introduction, Popper-Keizer entered with authority and passion, quickly engaging in a beautiful dialogue with a rich and sonorous flute line.

The viola soloist, Lisa Suslowicz, was taut and clear throughout.

Adeptness in the orchestra was always evident, with descending violin cascades well-coordinated and lyrical sonorities abounding.

The central meditative portion, entitled The Knight’s Vigil, was treated with beauty and tenderness by Popper-Keizer, and, at the end of the piece, in a finale entitled The Death of Don Quixote, he played with a clear and resonant sense of noble departure.

The concert opened with a little-played Sibelius piece that used its mythological underpinnings to tell a tale of passion and romance. Starting with a middle-voiced chordal brass fanfare, the piece transitioned to a folkish romp layered over a rhythmic heartbeat. Playfully bowed thematic gyrations by the front desk strings anticipated the sonorous love music introduced by the cellos in unison. The piece ended quietly and sweetly, with three settled and resolute sonorities.

If anything, this evening was an embarrassment of riches. It was a bit long, especially with Zander’s welcome and informative commentary, stretching near three hours. The soloists were both superb, but, in a way, it was like two gourmet dinners rolled into one, endlessly tempting, but a lot to take in at once.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply