Lecture by

Howard Gardner

Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education

Harvard Graduate School of Education

Harvard Club, Boston

30,000 years old

At the recommendation of my dear friend and old roommate Jim, a child psychologist who got a degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, I went to hear Howard Gardner, Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at that school, give a lecture based on his recent book: Truth, Beauty and Goodness Reframed: Educating for Virtues in the Twenty-First Century. That book was a result of a series of lectures Gardner had given at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2008.

He spoke at the Harvard Club in Back Bay as a benefit for the Boston Landmarks Orchestra, a wonderful group founded in 2001 by the late Charles Ansbacher, an inspired leader, a visionary and a great conductor. As conceived and named, the Landmarks Orchestra would give free symphony concerts at the sites of various Boston historic landmarks. Gardner has been a supporter and overseer of the orchestra for years.

Gardner’s name is usually associated with the theory of multiple intelligences which he developed to help contextualize what we frequently take for granted, by means of evaluative tools like IQ tests, as the unitary standards of intelligence.

According to his multiple intelligences model, those tools tend to evaluate only a small subset of the seven general categories which otherwise include visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, linguistic and logical-mathematical forms of intelligence.

Because he is known so well for this theory, Gardner’s profound interest in art, developed from early in his career, is not always as well recognized. One might well argue, in fact, that a principal motivation for the development of his multiple intelligences theory derived from those early aesthetic involvements. Project Zero, which Gardner supervised for decades, and continues to guide, is devoted to the cultivation of education in the arts.

In the Harvard Club lecture, Gardner focused principally on the the theme of beauty.

In trying to answer the questions “what counts as beauty?” or “what makes something beautiful?” Gardner identified three principal guidelines:

it has to be interesting

it has to have a memorable form

it has to promote a desire to revisit it.

In elaborating the first point, Gardner invoked a research observation on the distinction between varied and repeated stimulus. According to psychological studies (he did not quote the sources explicitly, but that did not draw away from their curious implications), a work generates interest when it has enough variation to create a sense of the unexpected, but not so much that its twists and turns are jarring.

This general point – about desired degrees of variation – seems to cohere with the work Gardner has done with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi who has developed a notion of Flow that is based on similar criteria.

According to that theory, a subject feels great satisfaction when there is an appropriate balance of material that makes one feel equally competent and challenged. A satisfying job is one that is challenging, but not so much so that it is overwhelming.

Similarly, in aesthetic encounters, Gardner suggests that repeated stimulus gives the subject a grasp of the contour of a work while varying stimulus keeps that contour interesting; as long as they are in appropriate balance, the work is accessible but interesting.

Gardner’s second point centered on the memorable form of a work.

He recalled having heard years ago at Tanglewood a performance of Brahms’ First Symphony conducted by Leonard Bernstein, and having thought, at the time, that the performance was not only good, but memorable. He noted reading some time later a piece by the New York Times music critic John Rockwell who also identified that same performance as memorable.

I had an experience of this sort a couple of years ago when I heard James Levine conduct the farewell series of the Otto Schenk production of Wagner’s Ring at the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

I am not a fervent Wagnerian and do not brim with spontaneous enthusiasm – as some of my friends do – about his music. But there I was at the performance of the second opera in the Ring, Die Walküre (The Valkyries), and Placido Domingo (whom one does not automatically associate with Wagnerian roles) was singing the role of Siegmund. It was breathtakingly good. After the first act of the opera, I met some ardent Wagnerian friends who were also there and all of us agreed, immediately, that this was a memorable, even an historic, performance.

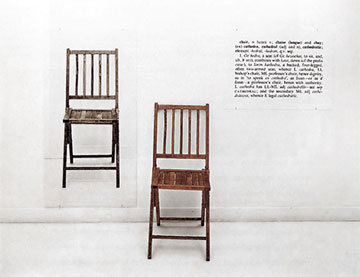

Copyright 2010 Joseph Kosuth/Artists Rights Society

Image courtesy of Museum of Modern Art, NY

Exhibiting a fervent interest in contemporary plastic art, Gardner called to mind a piece by Joseph Kosuth entitled One and Three Chairs (1965) that, for him, embodied this sort of memorable quality. In that work, a photograph of a chair, a chair, and a verbal definition of a chair are framed together. In a single image, the piece represents a kind of Platonic fusion of image, concrete form and ideality.

One might indeed well argue that this sort of Platonic urge lies deeply in Gardner’s approach to art and in his philosophy of education.

It would be a much longer story to try to bring out those influences, but suffice it to say that this broad ranging interest in art and its relation to virtue, so central to Plato, provides a classical backdrop for the contemporary explorations Gardner offered here.

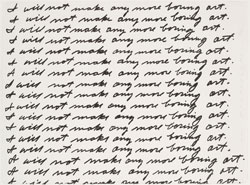

Image courtesy of John Baldessari

and Museum of Modern Art, NY

As another example of memorable form, Gardner invoked John Baldessari’s I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971), a visual depiction of a repetition of identical statements to that effect, much like a child punished in a school classroom might have to write.

Curiously, Gardner, an innovative educator who would be so obviously opposed to traditionally oppressive methods like having to write something over and over as a means of punishment, finds this evocation in Baldessari’s piece of memorable interest.

Indeed, semiologically, the work does create great interest, by bringing the emblem of repetition (and boredom) intimately into the realm of that which must, at all costs, avoid it.

The piece itself, while indicating its mission to avoid boring art, in its very repetitiveness, threatens it. But by forcing an opposition between the threat and the avowed meaning, the threat is superseded, producing something interesting and memorable. Curious!

In talking about the third criterion of the beautiful, inviting the desire to revisit, Gardner brought up Rheinmetall/Victoria 8 (2003) by Rodney Graham, in which an old film projector displays an image of a typewriter being covered by snow. Acknowledging the tendency one might have to regard this as a silly ploy rather than as a work of art, Gardner indicated how, on viewing this work, he was drawn back to it repeatedly.

As well, he called to mind Werner Herzog’s film Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) about the prehistoric paintings in the Chauvet caves in southern France. The film, through its subject-matter and its own artistry, invites, for Gardner, revisitation to those amazing creations of thirty thousand years ago in a compelling way.

In a brief allusion to the larger thesis of his book, Gardner distinguished Beauty, as a divergent phenomenon, from Truth, as a convergent one.

As divergent, Beauty manifests itself in a broad range of ways; because it is so dependent on individualized vision, there is no single guideline for what is beautiful.

Truth, alternatively, is convergent in that it represents a bringing together of hypotheses for testing and evaluation; not dependent on individual vision but on common standards of verification, it symbolizes that upon which we agree rather than than which differentiates each of us.

Curiously, in the discussion after the formal talk, Gardner said something like the following (I am paraphrasing) about artistic genius: it represents a relentless urge to reveal deep truths about the world.

Despite the earlier distinction between Beauty (as divergent) and Truth (as convergent), here was an invocation of a usage that suggested arenas for further elaboration and ramification.

That might well prod students of Gardner’s thought to further explore its Platonic implications by which Truth and Beauty form important connected avenues to that which, in a culminating vision, Plato calls The Good.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply