Panel Discussion With Robert Brustein (Moderator), Tina Packer, Jeffrey Horowitz, F. Murray Abraham

Arts Emerson

Paramount Theatre Mainstage

Boston, MA

This spring, Arts Emerson will be bringing New York’s Theatre for a New Audience production of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice to Boston.

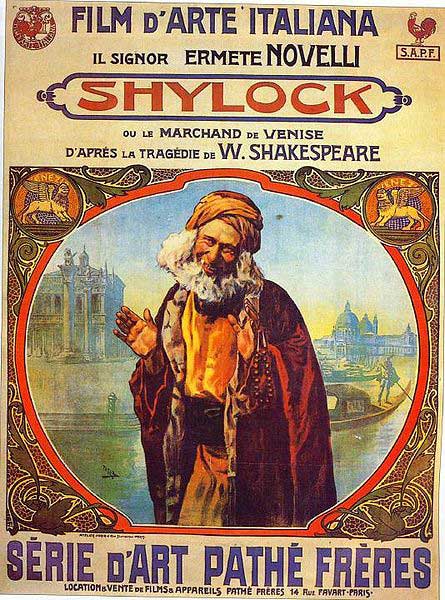

In anticipation of that run, several theatre luminaries showed up on the Emerson stage to discuss the complexities and interpretive challenges of this popular Shakespearean work which is noted for its not at all flattering depiction of Shylock, the Jewish antihero of the play.

The panel included F. Murray Abraham, the distinguished actor who will portray Shylock in Boston’s production as he did previously in the New York version. As well, Jeffrey Horowitz, founder and artistic director of Theatre for a New Audience, and Tina Packer, founder and artistic director of Shakespeare and Company, from Lenox, MA joined the discussion. Robert Brustein, one-time director of the Yale Repertory Theatre and dean of the Yale School of Drama, and, subsequently, the founder and director of the American Repertory Theatre at Harvard, moderated the discussion.

In a reflective and vulnerable way, Jeffrey Horowitz indicated his motivations for producing, in recent seasons, several plays with major Jewish characters: The Merchant of Venice, Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta, and an adaptation of Dickens’ Oliver Twist (also produced at the American Repertory Theatre a couple of years ago) which here achieves relevance through its depiction of the Jewish character Fagin.

Horowitz indicated that he had grown up in a Zionist household and that this had inspired, with subsequent reflection, his interest in exploring Jewish themes. Curiously, his study of The Merchant of Venice led him to believe that Shakespeare’s strongest drive behind the play lay not, as is frequently feared and believed, in expressing anti-Semitic prejudice, but in exploring the psychological effects of xenophobia, the scorning of outsiders. For Horowitz, Merchant’s depiction of Shylock is not a conventionalist prejudicial account of Jewish greed and heartlessness, but an exploration of the psychology of anyone kept on the fringes of society.

The other panelists generally concurred. F. Murray Abraham argued that in Shakespeare’s time Jews had been banned from England for centuries and that it was unlikely that Shakespeare knew any Jews, hence, could not have really been an anti-Semite. Though Abraham averred that Merchant , as a work, exhibits an undeniably anti-Semitic portrait, he argued that Shakespeare’s depiction of Shylock was not based on any personal antipathy for Jews.

Tina Packer charmingly but persuasively countered this with a note about Jews Shakespeare might well have known, including several traveling players, and, as well, a personal physician to Queen Elizabeth. Abraham’s point was still well-taken, though the nuance of Packer’s observation was important and illuminating. Though Shakespeare might have known some Jews, there were not too many of them in England during his lifetime: they had been banished in 1290 and had not been allowed to return until 1655, almost forty years after Shakespeare’s death.

During Menasseh ben Israel’s travels to England, the young, outspoken philosopher, Baruch Spinoza, then a member of the Amsterdam Jewish community, was brought before a Jewish tribunal and excommunicated for what were considered his heretical views. Spinoza’s excommunication is often interpreted as a protective response by the quite new Amsterdam Jewish community (which arrived largely from Portugal in the wake of the Spanish Inquisition) fearful that a young iconoclast (Spinoza was 24) would incite anti-Semitic reaction from the Dutch.

All the panelists seemed to agree that Shylock’s ferocity in Merchant only emerges when his daughter, Jessica, is absconded in love by Lorenzo, a friend of Antonio, the eponymous merchant of Venice. This represented a personal threat much more significant than the more obvious complaint of money not repaid. Shylock’s rage is incited as a father threatened with the loss of his daughter to an outsider and a non-Jew, not as a money lender who seeks brutal compensation as repayment for a loan.

Shylock and Jessica by Maurycy Gottlieb (1856-1879)

Shylock and Jessica by Maurycy Gottlieb (1856-1879)In a very funny and wise turn, Robert Brustein argued that Merchant , despite its avowed character and theme, is less a true psychological portrayal of a Jewish father than King Lear, who frets, and ultimately falls apart, because his children abandon him. It’s a brilliant analysis which, in a double turn, allows lovers of Shakespeare and Jewishness to find a sympathetic and mature association in Lear, and to regard Merchant as a less-evolved portrait of the paternal theme, a kind of caricature, rather than an inner portrait, of the Jewish parental soul.

This oblique argument was perhaps the most effective in countering the discomfort one naturally feels in approaching Merchant. Through its irony, Brustein helped to sidestep the obvious counterargument that the play, in glorifying Portia’s battering of Shylock, is not so much an exploration of xenophobia as an embrace of an anti-Semitic stereotype.

Each of the panelists was uniquely endearing: F. Murray Abraham was self-deprecating in perfectly timed moments that allowed the audience to laugh easily. Tina Packer was pungent and direct while being light, allowing her abundance of knowledge and insight to flow without it feeling forced. Brustein was an effective and knowledgeable moderator and Horowitz was heartfelt.

In a nicely revealing turn, but couched it in the spirit of sensitivity, mutuality and cross-cultural theatrical exploration, Brustein pointed out that F. Murray Abraham, though appearing Jewish and having a Jewish sounding name, is of non-Jewish Syrian extraction. It framed and gave poignancy to Abraham’s clear avowal of Merchant‘s unappealing anti-Semitic stereotyping while recognizing the play’s other clear virtues.

One of the penetrating moments of the evening came near the end, as panelists noted how Horowitz had, in New York, at the time of the Theatre for a New Audience production of Merchant , arranged a plethora of discussions and forums about Merchant and Jewishness, and that this larger educational and communicative sense of purpose surrounded the production with a kind of humanistic glow that represented as much of the significance of the event as did the production itself. It was a testament not only to Horowitz and his noble intentions, and actions, but to the idea that, within contexts of learning and discussion, theatre can stretch deeply into our lives and give us untapped interpretive opportunities.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply