Comic Opera

Music By Arthur Sullivan

Lyrics by W.S. Gilbert

The Harvard-Radcliffe Gilbert & Sullivan Players

Agassiz Theatre in Radcliffe Yard

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Stage Direction by Sara Libenson

Musical Direction by Jesse Wong

April 16 – May 2

A friend of mine who loves Gilbert and Sullivan (and who, most admirably but annoyingly, remembers most of the lyrics to everything) has a young friend in this show and reminded me about it. I am very glad that I went. I was just getting back from an event in New York and was exhausted and not quite sure I was up for an evening of G&S, but I was quickly dissuaded from my hesitations once the overture began and the curtain went up. This is an excellent, imaginative and energetic production.

The story of Pirates is, of course, completely ridiculous. If, for a moment, you might have thought that Monty Python’s wacky deconstructive humor had no antecedents in British theatre, think again. Librettist W.S. Gilbert’s command of the relation between logic and its demented mirror-self is impeccable. British philosophy has always prided itself on logic, and it is most fortunate for British culture that Gilbert and Sullivan (and Monty Python, of course) have been on hand to add a healthy dose of illogical extrapolation to that august self-image. Thanks to them and their like, anybody who appreciates the broad landscape of British culture will find that its logic and sense of propriety do not go unmolested and unsatirized for long. And, at every possible turn, this sensibility turns any hint of seriousness in the plot of Pirates into ridicule and whimsy – and it is sheer delight.

The silliness and ridicule carry weight, nonetheless. Its victim is duty, wherever that may go, and the seriousness of its occupation, along with the aimlessness of its object, is the satirical bullseye. The romantic lead of Pirates is Frederick, whose sense of duty is so pronounced that he is dutiful in the extreme to whatever institution happens to hold him in tow at the moment. By ancestral contract, the pirates have got him until his twenty-first birthday, which now appears to have almost arrived. Frederick has been unremittingly devoted to the pirates until now. However, on turning twenty-one, he announces that he must alter his sense of dutifulness to renounce the pirates’ vile occupation and seek their turn to justice. But, alas, it turns out that Frederick’s birthday is on February 29th, which makes him twenty-one years old, but only five birthdays old. You get the picture. Delightfully ridiculous, and a beautiful extension of British logic into the realm of complete wackiness.

Naturally, there is love interest, equally played off between duty and attraction, and Frederick must wrestle between his rational and empirical selves in order to come to final resolution. All of it is still a hoot, a century and change after it was first produced in 1879.

The music for Pirates is intricate and, in some places, ferociously complex. Conductor and music director Jesse Wong does an amazing job of keeping the orchestra on track, and overall they do beautifully. Clearly it’s a student, not the Metropolitan Opera, orchestra, but the gist, the structure and the feeling of the score are so well interpreted that one easily overlooks the imperfections to absorb the wonderful musical character of the piece. That is not to say that the orchestra is not competent – it most certainly is – and displays technical virtuosity in some places, involving, among other things, maddeningly elaborate violin accompaniments. But Wong does a wonderful job of balancing the orchestra and choral parts and maintaining it in a subtle and nuanced way.

The direction and choreography are strikingly good – tasteful, inventive and very fun throughout. It takes real pizazz to make a very traditional show come alive and Sara Libenson has done a first rate job of putting in all sorts of little touches with gesture, movement and dance which are just delightful. The staging sparkles, and it seems that everyone has a magnificent time pulling the whole thing off.

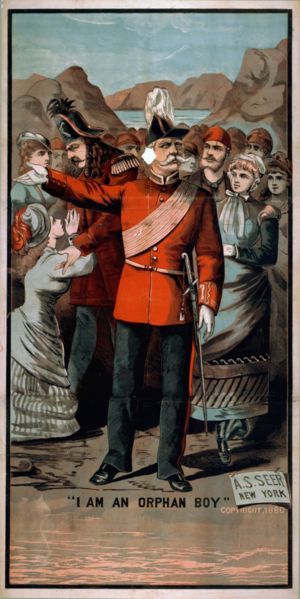

Ilan Caplan as the Pirate King is appropriately vagabondish, and bounds around the stage with a kind of bravado that one easily associates with Kevin Kline’s athletic performance in Pirates on Broadway in the 1980s. Caplan’s voice is capable but not operatic – its gravelly tone works in the role, and his swaggering histrionics, most appropriate, carry off the whole thing very well.

Benjamin Nelson as Frederick has a beautiful tenor – lean and taut, but sculpted, with dramatic and comedic phrasing built in nicely. There is real lyricism in his exposition of the part, and the vulnerable lightness of his tenor works well with the role.

Benjamin Morris as the Major General is just great, with mastery of the fabulous speed and lingual dexterity required for the profoundly challenging I Am The Very Model Of A Modern Major General number.

The supporting cast and choral groups of the young maidens, the pirates and the police are all very good. They sing beautifully, move beautifully, and seem to be having a great time.

Bridget Haile as Mabel, the female lead, has a real stand-out of a voice. Like her co-lead, Benjamin Nelson, it has a discernible lyrical grace, but it also has a powerful richness and breadth. It would be interesting to hear what she might do with other operatic roles.

Overall, this is a great production and a real tribute to Gilbert and Sullivan. Its musical poise, creative staging, and wink of the eye that indicates that all are having a good time, makes it very enjoyable. And it is a particularly wonderful exhibition of the talents of the young people who continue to cultivate this tradition at Harvard year in and year out.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply