Film (2013)

A documentary by Mark Levinson and David Kaplan

Directed by Mark Levinson

Produced by David Kaplan

Kendall Square Cinema, Cambridge, MA

Music by Robert Miller; Cinematography by Wolfgang Held, Claudia Raschke-Robinson; Film Editing by Walter Murch

With Martin Aleksa, Nima Arkani-Hamed, Savas Dimopoulos, Monica Dunford, Fabiola Gianotti, David Kaplan, Mike Lamont

Photo: Courtesy of PF Productions

This engaging documentary is a lens into contemporary particle physics through the personalities of several players in different corners of the field.

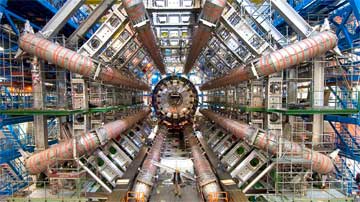

It begins with nice country shots of the landscape around CERN, the European home of the Large Hadron Collider, and a passing glance at a statue of the dancing Hindu god of destruction, Shiva. (Presumably destruction, in this context, refers to the smashing of atoms.) This center, which was under construction for decades before its activation in 2008, produced its truly landmark discovery in 2012 with the confirmed discovery of the so-called Higgs particle. Lots of shots of the collider, a five story mega-construction with a circumference of seventeen miles, provide a kind of continuing source of technological awe.

Photo: PF Productions

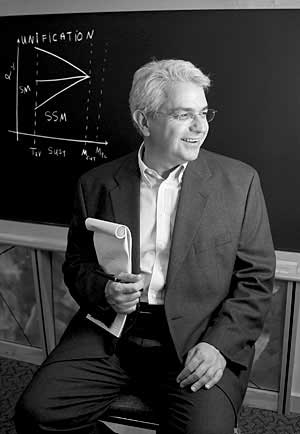

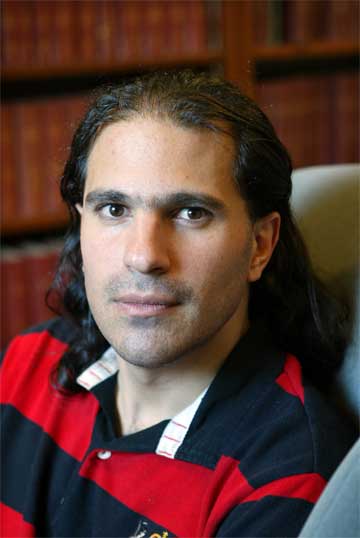

In short order, we get introduced to the first and primary host of the show – who also happens to be a producer of the film – David Kaplan, a theoretical physicist at Johns Hopkins University. We first see him, long-haired and with several days of beard but very good humored, in a hard hat at CERN getting a tour in 2007, still during the construction phase of the Large Hadron Collider. In interviews, we get a thoroughgoing sense of the drama from Kaplan, who says that the experimental results from CERN will be revelatory or intellectually damning: “Either it’s going to be a golden era or it will be quite stark.” And we get a clip, as we do throughout the film, of Kaplan addressing a lay audience of the Aspen Institute, giving a quite nice explanation of what the experiment is about.

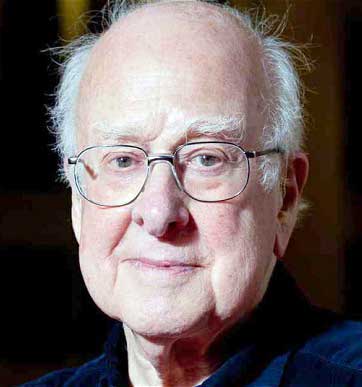

Photo: REX, The Telegraph

For a little while, the film features him so much that it begins to look like it might turn out to be The David Kaplan Show, but, as the film goes on Kaplan begins to blend into the woodwork and a series of other physicists take the stage, and his initial presence seems more like a nice, introductory personalized avenue into the subject rather than an opportunity for self-glorification. And it turns out that this personal sense of intellectual drama, the way in which aspiration, vision, and collaboration figure into this most rigorous form of scientific investigation, is what the film is really about.

Photo: Stanford University

After some basic facts about CERN – it’s attached to 100,000 computers around the world and it is where the World Wide Web was invented so intellectual information could be shared, and so on – we get introduced to Fabiola Gianotti, a top administrator at CERN, and a number of other physicists whose thoughts and profiles form the substance of the film. Included in these are Savas Dimopoulos from Stanford University, David Kaplan’s mentor, and Nima Arkani-Hamed of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, a rough contemporary of Kaplan’s, both leaders in the field of theoretical particle physics. With Arkani-Hamed, who Kaplan identifies as “the star of his generation,” there ensues a continuing group of scenes with truly impressive chalk scribbling. Arkani-Hamed writes out complicated formulas so ferociously quickly and seemingly effortlessly, not seeming to pause to think, that one is stunned into awed silence; it certainly makes for good video.

March 29, 2010

the day of First High Energy Collisions

Photo: ATLAS Experiment © 2013 CERN

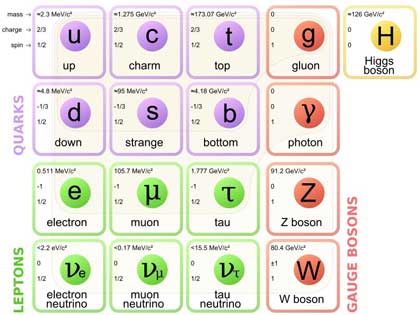

There is some elaboration on the so-called Standard Model of particle physics, and the importance of the Higgs particle in holding it together. Arkani-Hamed notes that the (at the time of the interview) projected experimental confirmation of the Higgs particle is “my generation’s only shot,” which also significantly adds to the drama of the discovery.

Certainly, anyone who has watched science news in the last few years has been aware of the CERN confirmation of the Higgs particle, which makes watching Particle Fever a bit like watching a Greek tragedy in which one knows the outcome but gets caught up in the drama nonetheless.

A young, post-doctoral physicist at CERN, Monica Dunford, becomes the focus of a good deal of air time when the film gets into the drama of discovery at CERN. She’s an energetic and enthusiastic speaker, communicates things in a down to earth way, and gives a good sense of the various climactic moments in CERN’s evolution. She’s there in 2008 to tell us about the first-beam test at CERN, to make sure the thing works at all. As she describes it, it’s the “first glimpse to see if the beam can run… after 19 years you’re now ready for this step.” And when, after what seems like a dramatic disappointment of the beam at first not working, then, after a second countdown, it works! Lively music with energetic cellos fills the soundtrack and at CERN there is lots of applause. As Dunford put it: “It worked. And there are so few times in life when it just works. We rocked!” And she is there in 2010 to tell us about the experiment in which the first actual collisions are attempted, successfully.

Photo: Institute for Advanced Study

Princeton, NJ

There are many other great scenes, not the least of which, certainly, is the day of the big announcement about the Higgs particle confirmation, replete with Higgs’ presence at CERN.

Photo: Monica Dunford

Symmetry Magazine

The film is not heavy on background. Apart from the scientists it features, one is hard pressed to find much about the great physicists of the preceding generations who laid the groundwork for these discoveries. That lack of background was, initially, a disappointment, but then I realized that was not really the aim of the film. It is not a comprehensive survey of particle physics, nor even much of an introduction to the fundamental issues in it. It is a small taste of the field and a larger taste of some of the personalities involved. It gives a warm sense of those personalities and what motivates them and helps to put a human face on a field which often seems more cold and abstract than it really is.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply