Film (2012)

Written and Directed by Quentin Tarantino

Cinematography by Robert Richardson

Film Editing by Fred Raskin

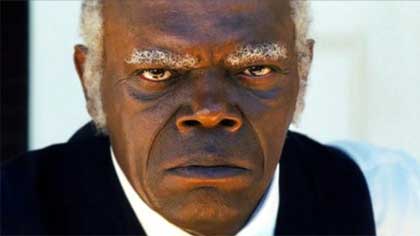

With Jamie Foxx (Django), Christoph Waltz (Dr. King Schultz), Leonardo DiCaprio (Calvin Candie), Kerry Washington (Broomhilda), Samuel L. Jackson (Stephen)

Jamie Foxx as Django

in “Django Unchained”

© 2012 Columbia Pictures

Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) is a bounty hunter who enlists the help of a liberated slave, Django (Jamie Foxx), to pursue a particularly big prize. Django is also after a big prize and their pursuits entangle and evolve more than either of them might have predicted.

I was not a big fan of Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) when it came out. Unlike many, who found it charming and funny despite its over-the-top depiction of violence, I did not. I could not somehow laugh along with it and found the brutalities disconcerting.

Gratuitous violence in works of art cheapens them and is unappealing; but, if violence is used thoughtfully, it can be a compelling vehicle for aesthetic catharsis.

in “Django Unchained”

© 2012 Columbia Pictures

In recent cinema, the distinctive case I call to mind is Martin Scorsese’s film, Goodfellas (1990), a brutally violent film, but such a good one that the violence, though unsettling, is completely understandable as an aesthetic vehicle.

Here, in Django Unchained, I was struck, during the first two thirds of the film, by how much I liked it. Frankly, I was surprised to find that Tarantino’s offbeat humor, despite the violence, really worked; here it came through loud and clear.

I am inclined to attribute almost the entire reason for the success in conveying Tarantino’s baroque sense of humor to Christoph Waltz’s impeccable performance as Dr. Schultz, the German bounty hunter.

The way his character teeters on the edge of insanity with a wry wildness, while unbelievably exhibiting a severe sense of control and governing intelligence, is distinctive.

While watching Waltz’s performance, I felt like, all of a sudden, I had a sense of what Tarantino has been up to all these years. His narratives work if one can see their brutalities as deeply connected to this explosive relationship between craziness and control.

And to see, in Tarantino’s settings, that this explosive relationship is an effective means for dealing with the world’s insanity gives this aesthetic choice even broader explanatory power.

Though Waltz’s performance here is virtuosic, the other major performances also come through well.

Jamie Foxx is dutifully heroic as Django, the unbound slave. He seethes with awareness as his state changes and he begins to carve out a bit of integrity; as he does so, Foxx gives Django an unbridled grace, as though he begins to dance through his newly found unboundness.

Leonardo DiCaprio is chilling as the villainous plantation owner, Calvin Candie, proprietor of the plantation Candieland. Who knew that sweet, under-appreciated guy from Titanic could be such a cold-blooded beast? He is most vividly and convincingly detestable here in a suavely demonic way.

in “Django Unchained”

© 2012 Columbia Pictures

Samuel L. Jackson provides an unblinking and unsettling depiction of a dutiful house slave. It is bizarre to think of his appearance and his role in Pulp Fiction and compare it to this completely different look and disposition. As it did in that earlier film, Jackson’s charisma reverberates.

There are a lot of worthwhile incidental moments throughout.

Jonah Hill has a very funny turn as a Klan leader who holds forth on the liabilities of sheeted-mask wearing during an attempted raid. It is a wryly unrealistic moment, more like a gag from a Woody Allen film, but bizarrely amusing, nonetheless, in its determined satire on a dire practice.

The German theme gets played up in an amusing and unusual way involving a woman slave whose name, derived from the German mythic Brünnhilde, is Broomhilda. That her story in the film fits with the mythical tale of Siegfried, as rendered in Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungen, is a cute twist.

The last third of the film suffers from a narrative choice that, in the end, weakens its dramatic thrust.

Tarantino had me up to that point and, remarkably, I was getting ready to package it up as one of the great films of the year. It is, for much of it, an extremely good effort, but falls through in those final chapters.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply