Film (2012)

Written and directed by Jeff Kaufman

New York Film Festival

Walter Reade Theater

New York, NY

The Savoy Ballroom, owned and operated by impresario Moe Gale from the late 1920s to the late 1950s, was the home of great music and perhaps the only place in New York during the time where whites and blacks could socialize and dance together. Places like the famed Cotton Club were homes to famous Afro-American musicians and dance performers, but, at that time, apparently catered to only white audiences.

Jeff Kaufmann has put together a labor of love as a tribute to the Savoy and to the great musicians, dancers and impresarios who gave it life during its early years. Through archival photographs, interviews and a continuous sound track of recordings of Chick Webb’s orchestra, one gets a vivid sense of the varied talents and accomplishments of the visionaries who brought this world to life.

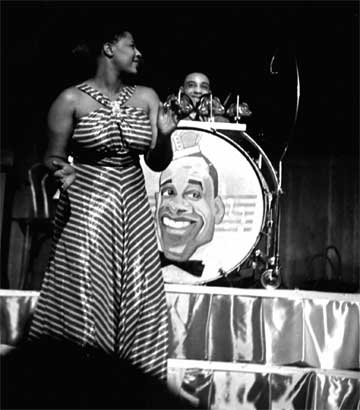

There is, centrally, the story of Chick Webb, who, despite severe physical infirmity, was able to exercise his great musical creativity as a drummer and a bandleader. It was he who gave the teenage Ella Fitzgerald her musical start and the film gives a real sense both of her incipient talent and of Webb’s insightfulness in cultivating it.

Moe Gale’s son, Richard Gale, a noted academic philosopher, provides a wonderful, down-to-earth account of his father’s acquisition of and history at The Savoy. As he points out bluntly, the twenty-seven year old Moe Gale, white and Jewish, bought The Savoy in 1927 purely as an investment. But, as Richard further notes, Moe’s sincere appreciation and love of these African-American musical artists grew to great proportions. Consequently, The Gale Agency, which Moe formed with his brother, became the leading manager of great African-American musical artists during this era, shepherding Ella Fitzgerald, The Ink Spots, and many others to greatness.

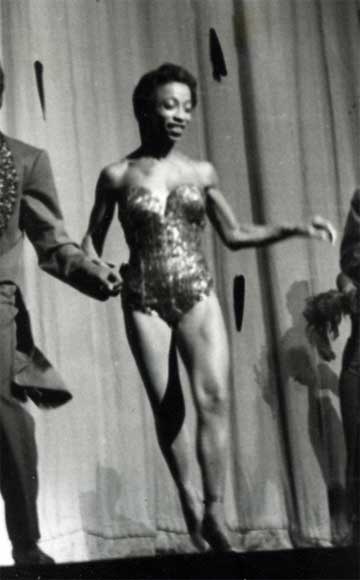

Norma Miller, now in her nineties, also provides wonderful interview footage, giving a vivid sense of what it was like to be a regular dancer at The Savoy in those days. She evokes a sense of the vitality of the club, a warm appreciation for the mixing of whites and blacks, a sense of the supportive environment Moe Gale helped to create, and a passionate feeling for the musicians and their work. And she dramatically brings alive the drama of the evening in 1938 when Chick Webb’s orchestra, with vocalist Ella Fitzgerald, lined up against Count Basie’s with Billie Holliday, in a momentous battle of the bands.

In a post-screening question and answer period, both Miller and Gale gave a vivid sense of the wonder of The Savoy, its cultivation of great music, great dancing and an open and integrated atmosphere.

Both gave straightforward accounts of the time as well. Miller noted the prevalence of color discrimination among blacks that enabled those with more lightly toned skin to have more privileged positions of employment.

In a poignantly troubling coda to this discussion, Jeff Kaufmann, the director, recounted, in answering a question about what happened to Chick Webb’s beautiful, light-skinned black wife after he died in his thirties, the following. Some years after Webb’s death, someone from The Savoy encountered her unexpectedly at a social event in another state. She pulled that person quietly aside and requested that her identity not be revealed since her current husband thought she was white.

Certainly, racism, in its many forms, persisted, but, there were moments of opening and change. As this lovely film shows, what happened at The Savoy during its years of greatness provided just such an opening, through which great black bands and vocalists came into their own, and whites and blacks encountered one another somewhat more freely.

The Savoy King has some rough technical edges, and its narrative might have been shaped with a bit more of a dramatic arc. Though not a consistently polished film, it is a deeply heartfelt one and gives a beautiful sense of a magical world that we might otherwise have encountered in only bits and pieces.

– BADMan

My father (Julius Dixson) had history with Moe Gale. He is the one who sent Otis Blackwell to Sheldon Music after hearing Don’t Be Cruel.

Julius Dixson is known for co-writing Dim Dim The Lights, It Hurts To Be In Love, Lollipop and many more. He also wrote and produced the number one The Clouds in 1959, which he put out himself on his Alton Records label.

If Richard Gale reads this I would like to meet him. – Julius Tajiddin (facebook)

Julius,

I was thrilled to learn of your post about your father and his relationship with Moe Gale. I’m Richard’s oldest son. I’m sorry to say that Richard passed away back in 2015. Richard had such sharp and vivid recollections of everyone he met during his stint in the music business. If you are interested in connecting, please feel free to reach out to me via e-mail @ andy.gale@aecom.com.

Best,

Andy