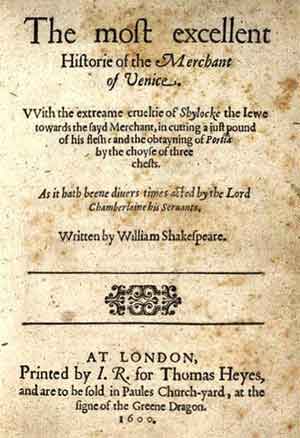

Play by William Shakespeare

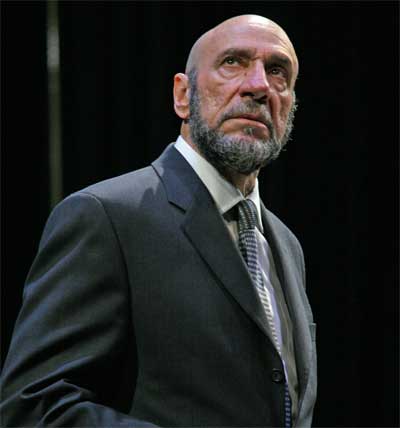

Starring F. Murray Abraham (Shylock)

With Andrew Dahl (Balthasar), Grant Goodman (Solanio), Lucas Hall (Bassanio), Kate MacCluggage (Portia), Christen Simon Marabate (Nerissa), Melissa Miller (Jessica), Jacob Ming-Trent (Launcelot Gobbo), Vince Nappo (Lorenzo), Tom Nelis (Antonio), Christopher Randolph (The Prince Of Arragon, Tubal, The Duke of Venice), Matthew Schneck (Salerio), Ted Schneider (Gratiano), Raphael Nash Thompson (The Prince of Morocco)

Directed by Darko Tresnjak

Produced by Theatre For a New Audience, NY

Artistic Director, Jeffrey Horowitz

Arts Emerson, Boston, MA

Cutler Majestic Theatre

Boston, MA

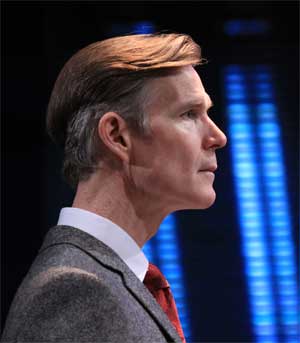

F. Murray Abraham as Shylock

F. Murray Abraham as ShylockTypically, The Merchant of Venice is played as an exuberant conquest. And though, in recent years, there has been greater acknowledgment of the problematic quality of its inherently anti-Semitic theme, there is also a tendency to compensate for that by promoting the feminist grandeur of Portia’s ascendency and triumph. Though one winces at the continuing negative references to The Jew, one feels redeemed by the strength, resourcefulness and nobility of Portia.

This production, thankfully, gives a far more sophisticated reading. Though Portia’s strength is not compromised here, she is portrayed very much as a member of a restricted social caste, not as a goddess of universal justice. She is shown as a sly member of the landed gentry and exacts, with her considerable wit and verbal adroitness, a solution that benefits her peers. But, here, it is not so much justice that she effects. Rather, it is a kind of manipulation of a system that has the appearance of justice.

Kate MacCluggage as Portia

Kate MacCluggage as PortiaIn a wonderful rendering of the courtroom scene, the judge, standing high in the back of the balcony, receives Portia’s arguments. None of the arguments, as delivered here, is very persuasive. But the rendering of them, and the agreement of the judge to Portia’s recommendation of harsh treatment for Shylock, does come across as a subversion of justice.

Much of the reason for this effect is that, in this scene, F. Murray Abraham is so wordlessly effective. As Portia delivers her arguments and the judge capitulates to them one by one, Abraham crumples and collapses. Amazingly, the crumpling of his hope, of his spirit, and, most of all, of his sense that there could be any justice for him and his kind, becomes palpable. As the judge levies the sentence against Shylock, his, and our, faith in a just social context melt and disappear.

This is quite an incredible result from a play which is so easily rendered as a simple moral tale with Shylock as the villain. But, here, the failures of the society in which Shylock strives to compete are framed as the real sources of villainy.

This is a modern dress production and it is effective. Antonio, the eponymous merchant of Venice, is shown as a kind of creepy Enron executive type, cold and sleek. His friends Bassanio, Lorenzo and Gratiano are all drawn as Wall Street trader types, glib and callow. Poetry is allowed to emerge from their lips at some points near the end, but, for the most part, they are shown as take-it-for-granted, not very nice, upper crust, non-ethnic white society people.

Tom Nelis as Antonio

Tom Nelis as AntonioPortia fits right in with this characterization. Nerissa, Portia’s maid, played by Christen Simon Marabate, a woman of color, breaks this rule. That comes across as a little strange, given the strong effort to characterize everyone else in the cadre that way – she is wooed by Gratiano, friend to Antonio – but it does suggest that boundaries of inclusion and exclusion can be more complex than they seem.

F. Murray Abraham was extremely compelling, not only in the trial scene, but throughout. His depiction of Shylock’s collapse and vengeful turnabout after his daughter, Jessica, steals his money and runs away with Lorenzo, is riveting.

The acting was by and large excellent. Jessica’s role, which can be a total sidelight, had as much depth as the script would allow. Melissa Miller played her with texture and depth, beautifully conveying that the act of betraying her father does not come without pangs of conscience and regret.

Two small roles came across exceedingly well. Andrew Dahl as Balthasar, with few words, made continual dramatic and amusing turns, contributing far more to the fun than would be expected from the text. Jacob Ming-Trent as Launcelot Gobbo, was also hysterical, playing the role, with dreadlocks, as a guy from the ‘hood, beautifully turning Shakespeare’s poetry into street argot.

Jacob Ming-Trent as Launcelot Gobbo

Jacob Ming-Trent as Launcelot Gobbo Lucas Hall (Bassanio) had a kind of good-looking untrustworthiness that fed well into the larger embrace of callowness that surrounds all the apparent do-gooding. Vince Nappo (Lorenzo) looks like a clean-cut Kiefer Sutherland, adding well into the frat boy menage. Christopher Randolph and Raphael Nash Thompson did very funny turns as Portia’s unsuccessful suitors. Randolph also did a good job, from the back of the balcony, as the magisterial Duke of Venice.

Kate MacCluggage (Portia) successfully evoked a combination of classiness and wit, but done in such a way that her upper class identity was in high relief.

Above all, this production responded to, rather than skirted, the treatment of Shylock. This was central to the apparent intent of the production and one could only come away feeling satisfaction in its conscientiousness. In its view, apparent justice is not necessarily just. And acquiescence to the dominant class is not necessarily good.

Portia wins and the exuberance of the conquest leads to a kind of final harmony, so characteristic of Shakespearean endings. The courage and insight of this production leads us above and beyond complacency with this. After the incipient satisfaction of the resolution, we sit and stare at its troubled conclusion, realizing that exuberance is only a very preliminary inkling of real and fundamental social change.

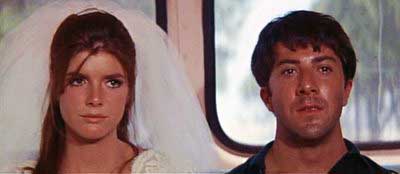

The ending of this top-notch production reminded me a good deal of the ending of the great Mike Nichols film The Graduate (1968). In that film, Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman in his first major role) and Elaine Robinson (Katharine Ross) jump on a bus, exuberant with having escaped from Elaine’s wedding, and presumably, from the empty life that surrounds and alienates both of them. After they get on the bus and the exuberance dies down, the final scene of the film shows both of them sitting, disheveled, staring blankly forward, seemingly into an equally empty future. What, in a moment of change, looks like liberation leads easily to a related kind of entrapment. Social context is not so easy to escape, and individual dramas, however compelling, are carried within its powerful currents.

Shakespeare and the Jews by James Shapiro

Shylock: A Legend and Its Legacy by John Gross

The Jews of Early Modern Venice, Robert C. Davis and Benjamin Ravid (editors)

Operation Shylock : A Confession by Philip Roth (Vintage International)

– BADMan

Leave a Reply