Play (2009)

by John Logan

Speakeasy Stage Company

Boston Center for the Arts

Boston, MA

January 6 – February 4, 2012

Directed by David R. Gammons

Scenic Design by Cristina Todesco

Costume Design by Gail Astrid Buckley

Lighting Design by Jeff Adelberg

Sound Design by Bill Barclay

Katie Ailinger, Production Stage Manager

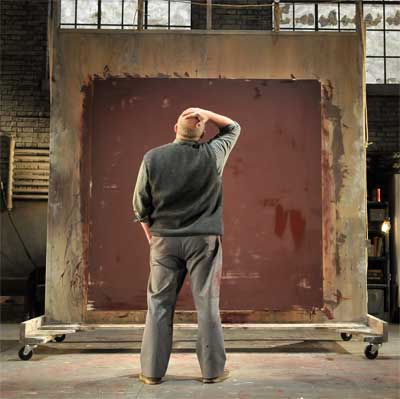

With Thomas Derrah (Mark Rothko), Karl Baker Olson (Ken)

Courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art

The late 1950s: Mark Rothko (Thomas Derrah), one of the 20th century’s (actual) great abstract expressionist painters, hires a studio assistant (fictional), Ken (Karl Baker Olson); the action takes place over the two or so years of his employment. Ken is an aspiring painter and hopes to get approval and guidance from Rothko, but it rapidly becomes evident that Rothko will not play that game.

Rothko’s commission to create paintings for the Four Seasons restaurant at the newly constructed Seagrams Building in New York provides dramatic focus. It is a commercial project: does it merit the attentions of this great artist?

And what, from his own deep, dark past, drives Ken’s interest in artistic catharsis?

Where, in Rothko’s impassioned, often angry, expressions with Ken, and his tribulations over the Four Seasons commission, are the anticipations of his own subsequent trajectory?

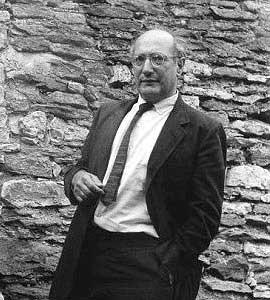

I saw Red, with Alfred Molina in the role of Rothko, a year and a half ago on Broadway. At the time, I thought the play decently, though not brilliantly, written. However, I thought Molina was a smashing success in the role. He captured the turbulently burdened bearing of his character with an astounding forcefulness (and with an undeniably authentic New York accent to boot). By the sheer power of his singularly excellent performance, I thought that Molina pushed the play ferociously forward to its great success.

Thomas Derrah, who plays Rothko in this production, is a very fine, seasoned actor who was in the company of the American Repertory Theatre for many years. I saw him in many roles there; though very capable and versatile, his performances sometimes struck me as a bit mannered.

Last year, however, Derrah appeared at the A.R.T. in the one man show – R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe – and hit it out of the park. He was so good and so compellingly believable as Fuller it was truly astounding. It was such a fabulous performance that, at the time I said – and still believe – that, were Derrah to take the show on the road, he could easily become to Buckminster Fuller what Hal Holbrook became to Mark Twain.

Fuller is a headier and less emotionally extreme character than Rothko; the Fuller kind of role strikes me as more naturally suited to Derrah’s bent.

But here, in Red, Derrah does a darn good job of conveying something much earthier and more dangerous. With considerable forcefulness, he puts forth Rothko’s self-absorption and passion vividly. This performance has a riskiness and weightiness that I do not immediately associate with his range.

An even greater power in Molina’s performance catapulted Red over the competition in New York and won it the Tony Award for Best Play in 2010.

Derrah’s performance is extremely good; but, even with a performance at a slightly lower voltage than Molina’s, some of the loose tissue of the play begins to show itself.

Photo by James Scott

Though the play is good and interesting in many ways, the scenario with Ken – which is manufactured by the author – frequently feels that way; the drama that ensues between him and Rothko follows an odd logic that also feels put on. As well, for the first long part of the play, Rothko expounds a lot about aesthetic theory, lending it the feeling of a dramatized lecture. And, the dramatic fulcrum – whether Rothko’s paintings will actually hang in The Four Seasons restaurant (though the event is drawn directly from history) seems wrongly framed.

It strikes me that at real issue in understanding Rothko’s eventual decline is not the question of purism versus commercialism (as exhibited by the Four Seasons dilemma), but, rather, the question about creative potency.

Rothko, much like Jackson Pollock, gained success and fame by capitalizing on a particular approach to painting which, in the end, seemed to ensnare him. Both Rothko and Pollock were geniuses, but they both got stuck in the vehicles of their own success. The tragedy – in both cases – is that the poetic accomplishments were so profound, but led to forms of aesthetic entrapment that spelled personal dead ends.

If we are to take Red‘s suggestion seriously, there is something about Rothko’s vainglorious insistence on being a poet-isolate rather than a merchant in the marketplace that foretells his self-destruction. That approach, I think, does not grasp the issue as profoundly as it might. Rather, it is the purity of Rothko’s drive towards poetry, and his eventual inability to break out of the restrictive idioms of his own aesthetic success, which trap him in despair.

Perhaps, if Rothko did as painter Frank Stella did several decades later, and threw his entire aesthetic approach to the winds and started over, there would not have been such a sense of limitation.

Logan’s play also suggests that Pop Art was waiting in the wings to destroy Rothko and Pollock in the way that, as emerging Abstract Expressionists, they had displaced their artistic forbears. That too seems like a too facile rendering of the history of mid-twentieth century art, and a too-easy way to rev up an hour and a half long drama. It is much harder to show how Rothko was more profoundly upended by his own dwindling capacity to find poetry in familiar stylistic idioms.

In addition to being passionate, angry and ultimately suicidal, Rothko was one of the great painter-poets of the 20th century. This play gives a more vivid sense of his anger and his passions, but does not convey much of a sense of him as a poet. Despair, rage and aesthetic urgency come through loud and clear, but there is not much in the way of lyricism. That feels like a missing piece of the narrative.

Karl Baker Olson (Ken) does fine as the foil. But when it comes Ken’s turn to come out of his shell and lay his cards on the table, it happens so abruptly it is difficult to see where it comes from. That too seems like a gap in the play’s narrative development rather than in Olson’s performance.

Distribution under GNU Free Documentation License

The staging and lighting evoke a New York studio nicely.

When Rothko and Ken prime a canvas together, it has a dramatic energy to it, though the ferocity and speed with which it was done in New York drew significant applause. The response in Boston was appreciative, but more muted.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply