Towne Art Gallery

Wheelock College

150 The Riverway

Boston, MA

Paintings by Kathi Packer and Richard Whitten

September 20 – October 20, 2011

Image courtesy of the artist.

Some weeks ago, I went to Wheelock College to attend a lecture and, making my way through the college’s Towne Art Gallery, was very happy to encounter the current show highlighting the works of two quite different but wonderfully inventive New England painters, Kathi Packer and Richard Whitten.

The title of the show, Details of Thought, does not, at first blush, give too much away; but, on experience and reflection, it does invoke a curious connective thread between the work of these two quite different painters. Had I been given the choice, I might have suggested, alternatively, Flights of Fancy; but the connective gesture would have remained similar.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Both of these artists operate from seemingly naturalistic foundations; but both stretch far beyond those foundations into imaginatively developed and visionary spaces. And both artists, while engaged in the serious enterprise of extending the quality of experience in those ways, are entertainingly and humorously ironic.

Packer’s work exhibits a naturalistic-ecological motivation, but also has surrealistic qualities. Whitten’s work is spatial and architectural, but its naturalistic basis – the internal structure of buildings – seems utilized principally as a perceptual muse. Thus, the notion of thought – as the exhibition title suggests – or fancy, as I might amend it – does, in a general way, capture the expanse demarcated by these quite different, but both adventurous and inspired, painters.

During that serendipitous visit, I spent my time looking at one of each of these artists’ works in some detail. Engaged by the distinctiveness of the exhibition, I returned a week and a half later for the opening; I then had the pleasure of chatting with both Packer and Whitten and getting a second viewing.

Image courtesy of the artist.

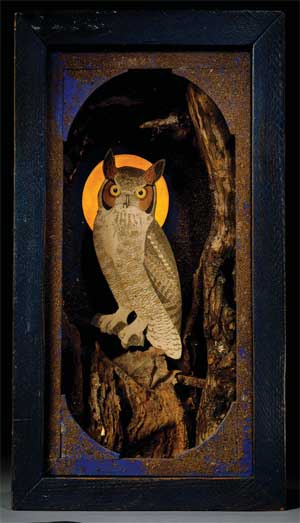

Packer’s Rats is a striking, tonally ramified, diptych, with its two panels aligned one above the other. Its bisected landscape is green and distant on top, and brown, leaved and close below. What seems like a capuchin monkey stares down from the top left overlooking the scene. A colorful bird – a macaw perhaps – stands on a root, center top, wings spread, cawing. A toucan with a lizard in its beak stands erect, top right, a green frog hanging onto a leaf cluster below it.

Beneath, in the brown-leafed space, rats squirm over the branches that magically extend down from above. One hangs from a root in the lower foreground; its large, vulnerable eye reaches out from center stage to the viewer, longingly and cautiously attentive.

This entertainingly ironic contemporary improvisation immediately suggests a multiplicity of allusions. By its horizontal eruption of a narratively rich expanse of wild landscape, the colorful world of Gauguin’s masterpiece Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? comes to mind. Though Gauguin’s work is populated principally by human forms, and Packer’s by rats, the integration of a dominant species with its environmentally diverse companions is a common thread; and from my discussion with Packer, I gathered that a viewer’s potentially imaginative association of rats and humans was a not unfounded extrapolation of her intentions.

As well, of course, Packer’s wild landscape suggests many of the works of Gauguin’s contemporary, Henri Rousseau. Though Rousseau’s scenes are wild, the dramas tend to be focal rather than gregarious, about individual creatures, or about dramatic, often combative, engagements between individuals.

Replace the humans in Gauguin’s great work with rats, add a dose of Rousseau’s landscape and whimsy, move it through a century of ecological reflection and one can begin to understand some of the sources from which Packer’s satirically romantic naturalism gains its footing.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The overt subject-matter of Rats brought Camus’ masterpiece, The Plague, immediately to mind. Whereas Camus’ rats, however, pose an oppositional complication for humanity, Packer’s rats seem to function as a kind of humorous proxy for it. Packer’s rats stare with human eyes; yet an apparent unawareness of their effect on the natural landscape calls out a wry judgement on a prevailing analogous inattention of humanity to the condition of the earth.

The two worlds of Packer’s diptych differ in space and context, but connect, artfully, by a flow of roots. What large tree connects the worlds of expansive vision above, and of terrestrial rambling below? Like these rats, we frequently move from one realm to the other with casual abandon, relatively unaware of their connection, or of the need to bring the enterprise of vision back into the service of the earth.

Image courtesy of the artist.

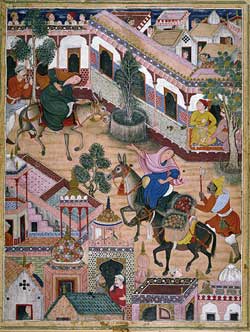

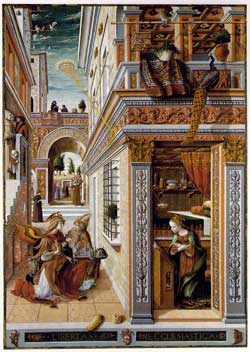

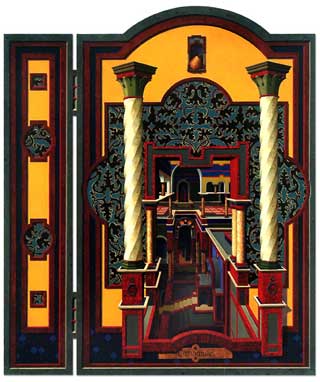

Campanile (1996) by Richard Whitten is a rich, dimensional and colorful architectonic of internal spaces, reminiscent of a Renaissance exercise in perspective. Its particularity of articulation calls to mind, as well, the spacial renderings of Flemish masters. And its bold coloration, its density of geometric form and its playful hints at narrative, suggest a distant familial relation to Islamist (particularly Mughal) paintings, which, though not spacious in quite the same way, magically and paradoxically convey dimension.

In Campanile, a pear sits framed in an alcove above. Blue, textured wallpaper with frond-like patterns subtend columns of varied shapes and hue, which in turn rise above artfully wrought pediments in vivid blues, reds and grays. A touch of green in the columnar pedestals and capitals calls out the sutble interstices of the multiple dimensions of the internal edifice.

In the catalog for an exhibition of his work entitled Passageways at Wheaton College (2009), Whitten mentions the more obvious influence of the architectural renderings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), but also suggests that works of contemporary artists like Joseph Cornell and Josef Albers – constructivist, but not specifically architectural – have made strong impressions.

Careful, challenging, geometric work exhibits itself in every corner of the canvas. Yet, there is something whimsical and fun here. This is not merely the depiction of a space, an academic rendition, but a lure to adventure. Imagine exploring a closet (as in the opening to C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe) and finding an amazing universe like this opening up behind? There is some of that adventure and fancifulness in Whitten’s work.

That whimsicality is reinforced in many of his paintings by the seemingly odd, but perfectly in tune, depictions of various oversize balls, frequently poised, contrapuntally, in the foreground. Are they reminders that we must remain playful to engage a work of art, to enjoy it, to organically inhabit its spaces?

Are they reminders, as well, of seventeenth century philosophers’ (Descartes and Spinoza, for example) depictions of mechanisms in nature? Mechanics and architectonics go together, and there is enough of the Renaissance and Flemish fascination with dimension here to indicate that reference.

But, here, the oversized irony to the pairing makes us dwell on the relation between mechanism and imagination, architectonics and adventure, structure and play, urging us to see that these so very carefully constructed spaces are not merely engineered icons, but recreational invitations.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Exploration, as the instrumental analogue to expanse, becomes the passcode to a kind of viewing: to inhabit the spaces which beckon, to follow their twists and corners, to enthrall oneself with their alluring geometries.

He also pointed out that the architectures he paints are more motivated by his upbringing in New York City rather than by trips to Italy.

With great technical specificity and delineation, Whitten creates a great hybrid of accomplishment and adventure. His works exhibit something crucial about the obligations of mastery in our age of technique: that it best connect well to human experience, to a sense of lived adventure and the imminent meanings of encountered wonder, or it loses its capacity for sustenance and for magic.

Whitten’s campanile – a bell tower – invites us to ascend its stairs and look down within its enchanted spaces. And we, as viewers, can respond to its clarion call to actively participate in its appeal to deepened and enhanced vision.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply