Film (2023)

Directed by Vasilis Katsoupis

Screenplay by Ben Hopkins

Based on an idea by Vasilis Katsoupis

Music by Frederik Van de Moortel; Cinematography by Steve Annis; Film Editing by Lambis Haralambidis

With Willem Dafoe (Nemo), Gene Bervoets (Owner), Eliza Stuyck (Jasmine), Andrew Blumenthal (Number 3), Vincent Eaton (Number 2), Daniel White (Ashley), Josia Krug (Jack), Cornelia Buch (Mabel), Ava von Voigt (Owner’s Daughter), Youl Samare (Doorman), Salim Karas (Flirting Guy)

Reviewed by Tim Jackson

in “Inside”

Image: Courtesy of Focus Features

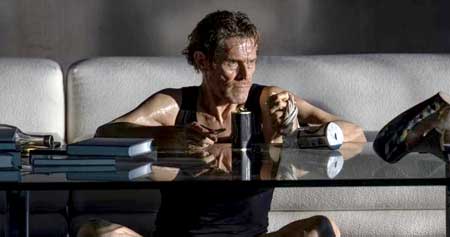

Willem Dafoe gives a tour-de-force solo performance as an art thief in the new film Inside. Dafoe, as an unnamed thief, has gained entrance to a penthouse apartment while the owner is overseas. Via walkie-talkie he is tasked with stealing four Egon Schiele paintings including a three-million-dollar self-portrait. When DaFoe enters an incorrect code on the apartment’s high tech alarm system, it sets off a screeching alarm, shutting off gas, water, and all access to the outside. Abandoned by his accomplice, he is trapped alone. A security camera and a plasma screen allow him see people coming and going in the halls and in the lobby but the alarm system has drawn no attention. No one can hear his screams or his pounding on the door.

Time is ambiguous but there is some indication that weeks are passing. It snows, a pigeon dies and rots outside the picture window. He resorts to eating old cans from a pantry, eventually consuming dog food, and tropical fish. He licks clean water from freezer condensation, then discovering timed sprinklers that water the indoor garden. With the plumbing gone, he shits in the tub. With the computer system down, indoor temperatures go from stifling to freezing.

With his bug eyes, broad grin and bony limbs, DaFoe suffers brilliantly (only by seeing the credits do we know the character’s name is Nemo). His opening words, which are repeated at the end, tell us that if his own apartment were on fire he would save three things: “My sketchbook, my AC/DC albums, and my cat, Groucho.” But, he explains, someone stole the album and the cat died. That leaves art as the only obsession remaining. Nemo, an artist himself, spends time sketching and, as he becomes more unhinged, creates a large wall mural complete with ambiguous symbols and a makeshift altar. What he needs for sustenance is art.

The art that he creates includes a towering structure built from pieces of demolished furniture secured with straps to make it steady enough to climb. Above his rickety construction of tables, chairs and pieces of furniture is a small skylight. He chips away at its concrete frame and uncovers bolts which, if successfully loosened, may offer a way out. He destroys the furniture, the paintings and objets d’art to build his structure and to vent his desperation. He is allegorically clearing away tradition to construct a new artwork that is both an exit and, metaphorically, a means of transcendence. Nemo, in Latin, means no one or nobody. If Nemo is nobody, stripped of individual traits, then, in a universal sense, is he everybody?

This allegory continues. In a hidden passageway he finds a rare manuscript of William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell. He reads from it: Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence. These contraries are, quoting Blake again, what the religious call Good and Evil. Good is the passive that obeys Reason. Evil is the active springing from Energy. Good is Heaven. Evil is Hell. A thief and artist, Nemo is all contradictions, stuck in his own Hell.striving and suffering for redemption.

Watching Inside, I was reminded of art movements that have explored new forms that ridicule and which criticize elite taste. Dada, Fluxus, Art Brut and Outsider Art champion the use of common things and elements of randomness. These artists sought new ways of perceiving the world beyond academic training and curatorial affirmation. Nemo, too, seeks freedom. Though his literal goal is survival, he is an artist compelled to create. The mountain of broken furniture that he hopes will be his salvation looks much like a work of Assemblage Art.

There are other signs that Inside is a kind of art commentary. On one wall of this apartment is a life-sized photo portrait of gallerist Massimo De Carlo, attached to the wall with adhesive tape. Nemo pulls that down. There – you’re free! he cries. The piece actually existed on a single evening for opening of a show by Maurizio Cattelan, the artist known for a fully-functioning toilet made of 18-karat gold (stolen) and a 2019 piece called Comedian, a banana duct-taped to the gallery’s wall (also stolen). Like the film, this sticking of a human onto a canvas is a striking and ambiguous commentary.

A slashed red canvas by Lucio Fontana, the father of Spatialism, adorns another wall: art and destruction. A more literal work of neon signage by David Horvitz reads All the time that will come after this moment. Is this a reference to transcendence?

A consideration of art history offers perspective on Inside. In 1971, the artist Chris Burden had himself shot in the arm as a work of art called Shoot. Jerry Saltz, writing about the event, says: “Shoot, as the work is known, is America’s Duchamp urinal: a cipher and a defining point of art. Lawrence Weiner once said that art isn’t just something that messes up the viewer’s day, it should “fuck up their whole life. That’s what Burton did to art from that day forward.”

Chris Burden is just one example. Paul McCarthy employs unorthodox materials in disturbing videos and sculptures. Performance artists such as Maria Abramović or Fluxus performers like Yoko Ono and Carolee Schneemann eschew the (moneyed) traditions in art for something more personal and often messy. Nemo certainly fucked up his whole life as he demolishes tradition along with everything in this moneyed art collector’s apartment. Inside, as an allegory, makes this film more than a survival thriller. The gaps in logic and credibility can be laid to rest. This is a comic tragedy, a satire.

Egon Schiele’s paintings, which flaunted convention, were the intended goal of the robbery. Defoe, as Nemo, begins to look altogether like one of the bony, desperate, attenuated figures in a Schiele painting. Nemo’s body and his efforts to survive become the art; his suffering is a path to transcendence.

Leave a Reply