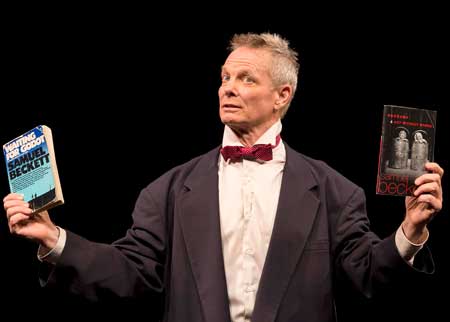

Performance (2022)

Conceived and performed by Bill Irwin

An Irish Repertory Theatre Production

ArtsEmerson

Produced by Octopus Theatricals

Emerson Paramount Center

Theater District, Boston

October 28-30, 2022

in “On Beckett”

Photo: Carol Rosegg

Courtesy of ArtsEmerson

This unique performance by the wonderful Bill Irwin is built around readings from a number of works by Samuel Beckett. Several of them are from Texts for Nothing (1950-1952) a collection of multiple prose pieces, from Beckett’s novel Watt (1953), and several from Beckett’s great play Waiting for Godot (1952). Irwin approaches Beckett and these selections with a warmth and intimacy that makes the audience feel as though he were just chatting, though it is clear that he has crafted this exceptional performance with immense attention to detail. The performance is so well conceived and put together that the enormous amount of effort clearly required to construct it does not intrude upon this sense of immediacy and informality. Ultimately, Irwin’s wonderfully thoughtful commentary and sheer expertise as a clown join with this sense of intimacy to deliver a superb and compelling performance.

Early on, Irwin gives a beautiful analysis and example of the Irishness of Beckett’s prose. While acknowledging Beckett’s dual linguistic commitments – to English and to French – Irwin captures, particularly in some of the passages from Texts for Nothing what that Irish lilt is about. As rendered so fluidly by Irwin’s delivery, the sheer intoxicating quality of Beckett’s words clearly comes through, though they frequently don’t deliver immediate linguistic coherence. But what is so great about Irwin’s approach, both in analysis and performance, is to reveal the innate mystery in Beckett’s writing that makes it so intoxicatingly elusive and compelling. Irwin finds and conveys, analytically and in his flawless and evocative renderings, how that transfixing elusiveness of meaning comes through in that lilt of Beckett’s writing.

Irwin points out that the particularity of Beckett’s images and references makes it feel very down to earth, while at the same time the haunting spaces in which those images and references are placed by Beckett yield a feeling of underlying mystery. While hesitantly and very briefly invoking the term Existentialism, Irwin conveys the important sense in which Beckett achieves, in narrative, an inducement to the existential stance – both grounded in the immediate and dumbfounded by it.

Irwin offers as well a couple of reflections on traditional interpretations of Beckett which he thinks go astray. One of these traditional interpretations is that solitary despair and a sense of bleak isolation are a fundamental trait of human existence. Rather, Irwin suggests that Beckett often paints these as disappointment in the breakdown of human relationship rather than as essential to human existence. That barrenness, where Beckett portrays it, is not, in Irwin’s view, just a lament about the innate solitude of human life but a reflection on the fracturing of connection.

He also counters the presumption by some Beckett interpreters that Beckett is not interested in or motivated by politics. For Irwin, the political is laced deeply into Beckett’s writing, though astutely and symbolically. In his view, Waiting For Godot, written in the late 1940s, is filled with political allusions and implications.

Bill Irwin as Vladimir

in Roundabout Theatre Company Production (2009)

of “Waiting for Godot”

Photo: Courtesy of Roundabout Theatre Company

Though On Beckett is full of erudition and pointed insight, Irwin takes pains to declare at the outset that he approaches Beckett not as a biographer or as a scholar, but as an actor. He does a wonderful job of conveying how actors, including himself, become obsessed with Beckett, and, in particular with Waiting for Godot. In so doing, he recounts the many productions of Beckett’s great play in which he has participated, including fascinating reflections on two celebrated ones in New York twenty years apart – one in 1988 with Robin Williams and Steve Martin and directed by Mike Nichols, and one in 2009 with John Goodman, Nathan Lane and Murray Abraham.

Throughout the ninety minute show, Irwin interlaces his clowning artfully to illustrate his points or to enact the passages he reads. At 72, his still lithe body seems made of rubber and every clownish gesture is alarmingly fluid, articulate and uproariously funny. What he does with a few hats and a large pair of pants is something to behold. One scene in which he does a gag about disappearing beneath an automated lectern brings one to tears of hysterical laughter.

This performance not only includes brilliant pearls of insight and commentary on readings from Beckett, but is supremely entertaining as well. One feels not only that one is watching and listening to a master at work but doing so with someone who has warmly invited you into his living room. This is a magisterial and eloquent performance, thoughtful, uplifting and hilarious, not to be missed.

– BADMan (aka Charles Munitz)

Leave a Reply