Play (2015)

by Lauren Gunderson

Directed by Debra Wise

Central Square Theater

Central Square, Cambridge, MA

September 22 – October 23, 2022

With Kortney Adams (Annabella Byron, Mary Somerville), Diego Arciniegas (Charles Babbage), John Hardin (Lord Lovelace, Lord Byron), Mishy Jacobson (Ada Lovelace)

in “Ada and the Engine”

Photo: Nile Scott Studios

Courtesy of Central Square Theater

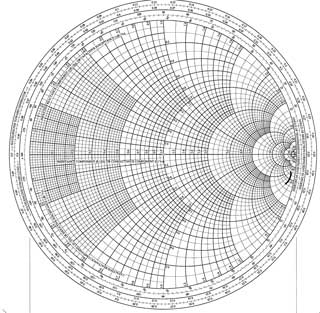

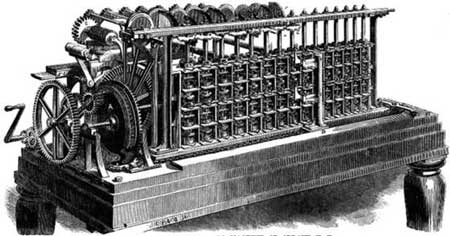

Ada Byron was the only legitimate child of famed Romantic poet Lord Byron but was abandoned by him as a child. Encouraged by her mother Annabella, she became a talented mathematician in her teens. Coming into contact with the significantly older mathematician and engineer Charles Babbage, Ada was immediately drawn to his conception of the Difference Engine, a mechanical device designed to perform complex mathematical calculations. The two formed a friendship and collaboration over the next twenty years, during which time Ada contributed significantly to Babbage’s vision for the Difference Engine and his more ambitiously conceived Analytical Engine, effectively setting out a design for a set of logical instructions that became the vision of the first programming language. Though the play suggests a strong emotional bond between Ada Byron and Charles Babbage, Ada went on to marry the man who became Lord Lovelace, had a number of children with him, but continued her intellectual collaboration with Babbage during those twenty years before her untimely death from uterine cancer.

This play about the brilliant young Ada Byron is beautifully written for the most part. The first three quarters of the play are a deft and articulate presentation of the setting of the work between Babbage and Ada Byron Lovelace. The play’s presumption is that a romance simmers intensely below the surface of their intellectual collaboration, though there is nothing in historical accounts that particularly supports this. Nonetheless, Gunderson sets the scene, and the production does a terrific job, of making this simmering romance vivid and persuasive. The depiction of romance is sufficiently obscured by the mores of the mid-nineteenth century to make the subtlety believable. Yet, despite the vividness and eloquence of the writing and the depiction, one wonders why Gunderson decides to make this simmering romance such a central feature of this play. It would seem that the genuinely central theme is that a very intellectually talented young woman with limited vocational resources in the mid-nineteenth century, finds through her collaboration with Babbage a form of intellectual fruition. That theme comes through loud and clear, but one wonders why Gunderson felt compelled to turn that collaboration into a potential romance.

Mishy Jacobson as Ada Byron Lovelace

in “Ada and the Engine”

Photo: Nile Scott Studios

Courtesy of Central Square Theater

In historic fact, Ada not only had a talented poet for a father – who engaged in a life of considerable libertinism and effectively abandoned Ada and Annabella before Ada got to know him – he then died when Ada was eight – but Annabella was a talented mathematician and was friendly with Mary Somerville, another mathematician who introduced Annabella and Ada to Babbage. Though Ada’s relationship with her mother was fraught in all kinds of ways, her mother and Somerville represented models of strong intellectual women. This is certainly indicated in Gunderson’s play, but the more central theme becomes Ada’s relationship with Babbage and, as the play sees it, her continuing unrealized love for him. Meanwhile, Lord Lovelace does a pretty good job of trying to accommodate his talented and eccentric wife. Though he does not think it proper for her to be carrying on, even intellectually, with Babbage, he comes around to figure out how to hold up his end in maintaining their marriage, have children, and enable her to continue collaborating with Babbage. The writing of these elements is interesting, but one wonders why, given the strong women with which Ada is surrounded, this issue of her presumed simmering romance with Babbage and her adaptation to domestic life with Lovelace take center stage.

Diego Arciniegas as Charles Babbage

in “Ada and the Engine”

Photo: Nile Scott Studios

Courtesy of Central Square Theater

By and large the writing is very good, and there are tons of quotable lines in the show, but there are a few points at which it falls short.

While it is historically true that when Ada was dying her caretakers kept close control over those who were permitted to see her, there is no particular indication that what Gunderson envisions as the exclusion of Babbage took place. Given the huge buildup of their subliminal romance, the depiction of this exclusion takes dramatic precedence and it does not really come off. The play, as well, also departs from history in one significant respect at this point as it does at various others; by historic account apparently Ada told Lovelace something personal of which no one ever found out the content which caused Lovelace to not see his dying wife in her final days. One supposes that she might have told Lovelace that she truly loved Babbage, but that is pure speculation. In the play, Lovelace becomes one of those who militantly prevents Babbage from seeing Ada, but that just does not square with what has come before. Though one must regard an artistic interpretation of history as valid on its own terms, some of the mixture of history and artistic departure from history can become not only confusing but render some of the art on its own terms less effective than it might be. The history shows that Ada’s caregivers kept people from visiting her at the end of her life, but the artistic departure which sets Lovelace excluding Babbage does not cohere in artistic terms with what precedes it.

Mishy Jacobson as Ada Byron Lovelace

Diego Arciniegas as Charles Babbage

in “Ada and the Engine”

Photo: Nile Scott Studios

Courtesy of Central Square Theater

After Ada dies, there is a long scene – way too long – that features Ada with her dead father – speculating about the birth of binary representation and a lot of other stuff. A group song gets stuck in here as well and it seems way out of place. The tone of this dramatic coda is very different from that of the rest of the play and the whole thing seems like a gratuitous add-on. Supposedly it gives some explanation about why Ada chose to be buried next to her father rather than her husband, but it goes on much longer than seems useful and has a jarringly distinct tone that threatens to unsettle the effect of the rest of the play. The play without this coda would have been totally fine and far better off without it.

Despite this peculiarity at the end, the play is masterfully directed by the very talented Debra Wise, and expertly acted by the troupe. Not only does Mishy Jacobson give a wonderfully spirited account of Ada, but, as well, she is a most capable classical pianist and fills the stage with several wonderful musical excerpts, including a quite long introductory one from Invention 4 in D minor from Bach’s Two Part Inventions. As Babbage, Diego Arciniegas is very convincing in both intellectual and romantic dimensions. He manages to convey the sense of the mentor who knows his much younger acolyte is not a suitable mate, but who finds it most difficult to resist their mutual attraction. As Lovelace, the energetic John Hardin gives a formal and dignified account of the somewhat confused husband, but carries it off persuasively; he also does a wilder turn in the weird dramatic coda as Lord Byron, showing how provocative, irreverent and unbuttoned is his character in contrast to Babbage, and to Lovelace. Rounding out the cast as the capable but fearsome Annabella Byron and in a quick supplemental turn as Mary Somerville, Kortney Adams does a respectable job.

Overall, the production is beautifully done, with most adept direction by Debra Wise who seems to bring the very best out of her actors. The theme of this show – the intellectual brilliance of a woman with limited means to realize it in the mid-nineteenth century – but the very capable realization of some of that brilliance by virtue of her sheer gumption – is a compelling one. Illuminating the intellectual history reasonably well while adding some speculative romantic flavor to the mix, playwright Gunderson provides the textual basis for this stimulating and entertaining production, realized so beautifully by this talented director and troupe of actors.

– BADMan (aka Charles Munitz)

Leave a Reply