Play (1611)

by William Shakespeare

Directed by Steven Maler

Commonwealth Shakespeare Company

Boston Common, Boston

July 21 – August 8, 2021

Levi Philip Marsman: Choreographer/ Movement Coach, Clint Ramos: Co-Scenic Designer; Jeffrey Petersen: Co-Scenic Designer; Nancy Leary: Costume Designer; Kat Ibasco: Assistant Costume Designer; Steven Doucette: Props Artisan; Eric Southern: Co-Lighting Designer; Maximo Grano De Oro: Co-Lighting Designer; David Reiffel: Composer/Sound Designer

With John Douglas Thompson (Prospero), John Lam (Ariel), Siobhan Juanita Brown (Gonzala), Remo Airaldi (Antonio), Nora Eschenheimer (Miranda), John Kuntz (Trinculo), Nael Nacer (Caliban), Richard Noble (Alonso), Maurice Emmanuel Parent (Sebastian), Fred Sullivan Jr. (Stephano), Michael Underhill (Ferdinand), Ekemini Ekpo (Ensemble), Duncan Gallagher (Ensemble), Jessica Golden (Ensemble), Marta Rymer (Ensemble), Dylan C. Wack (Ensemble)

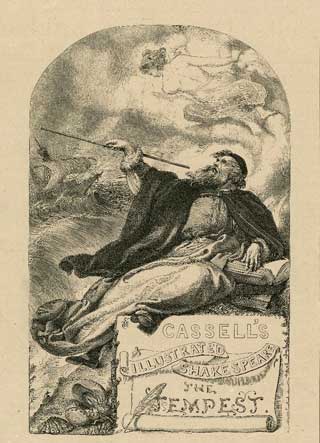

in “Cassell’s Illustrated Shakespeare: The Tempest”

Engraving by William James Linton, 19th century

Image: Folger Shakespeare Library

The delta variant of COVID is here now in full force but, despite that, Boston’s robust Commonwealth Shakespeare Company has presented its twenty-fifth season of productions on the Boston Common. This summer’s production of Shakespeare’s late but very great The Tempest has been pared down a bit to avoid the complication of an intermission in order to minimize contact during the pandemic. The show runs just about two hours, which enables it to touch the major parts of the play without getting lost in the weeds.

The production is trim in a number of other senses as well, but also fit. The set is minimal, but whatever is done with drapes and lights makes up for any loss of more majestic architecture. In the initial scene of the blowing of the storm itself, the entire cast comes out to wave the drapes and give a sense of the torrential and it works well. Costumes are also trim rather than elaborate, but that, as well, is no matter.

The story focuses on Prospero (John Douglas Thompson), a deposed duke – actually forced out of power by his evil brother Antonio (Remo Airaldi) and some complicit gentry, including King Alonso of Naples (Richard Noble) and Sebastian (Maurice Emmanuel Parent), both of whom show up in the action. Prospero, along with his baby daughter Miranda (Nora Eschenheimer), had been put out to sea on a raft years before, expected to perish. But they wound up on a desert island where Prospero, already bookish as a duke, had somehow transpired into a wizard. Not only is Prospero a wizard, but he has access to a sprite, Ariel (John Lam), who does his bidding and makes magic things happen. Without going into the complex details – there’s a downtrodden slave of Prospero’s named Caliban (Nael Nacer) who has a whole story as well – Prospero causes a storm to rise and to shipwreck a boat loaded with his brother Antonio, Alonso the King of Naples, Ferdinand (Michael Underhill) the King’s Son, and Sebastian the other conspirator. In short, Ferdinand and Miranda fall in love and with Ariel’s help Prospero teaches the others a good lesson. A couple of attendants along for the cruise, Stephano (Fred Sullivan, Jr.) and Trinculo (John Kuntz), conspire with Caliban to kill Prospero, but, they too, in the end, all get chastened.

Nael Nacer as Caliban

in “The Tempest”

Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva

Courtesy of Commonwealth Shakespeare Company

There are touches in this sleek and graceful production that really add to it. At the beginning, the cast comes out breathing heavily, somehow as though human breath were the forerunner of tempestuous weather. It’s a lovely twist, and particularly instructive in the era of climate change. As well, the music by David Reiffel, some of it tribal and instrumental, but some of it vocal, is extremely evocative. There are three women sprites (Ekemini Ekpo, Jessica Golden, Marta Rymer), who show up doing wonderful harmonies at various intervals. One is almost inclined to think of them as Shakespearean analogues to the Wagnerian Rhine Maidens of The Ring of the Nibelungen, but they are, in fact, quite a bit more down to earth in The Tempest than in Wagner. Despite its mythic qualities, The Tempest always reminds us of the natural and social worlds within which fantasy operates; with Wagner, one often thinks the opposite is going on.

In the role of Prospero, John Douglas Thompson has a majestically compelling character, conveying warmth and wisdom while remaining unyielding in the somewhat surprising moments where that occurs. His delivery of the final soliloquy in the epilogue is wonderfully articulated and compelling.

As Miranda, Nora Eschenheimer has a particularly straightforward form of delivery that makes many of her lines, given directly but with condensed feeling, fall square on the audience and draw accepting laughs. As Ferdinand, Michael Underhill is perfectly charming and seems the appropriate foil for Eschenheimer’s Miranda.

As the clowns, John Kuntz (Trinculo) and Fred Sullivan Jr (Stephano) give some rousing laughs. Kuntz is a particularly talented comic actor, having shown up in many comedic Shakespearean roles in Boston’s Actors’ Shakespeare Project; but Sullivan goes along for the comic ride very adeptly.

The great Nael Nacer takes on Caliban in this production, rendering him appropriately as a combination of the comedic and the pathetic. Nacer’s capacity for nuanced delivery is not evident here, since Caliban does a lot of grunting. But, in the final scene, when Prospero forgives Caliban and gives him his freedom, the hug that Nacer’s character gives to Prospero is moving and resounding – and that is a wonderful, subtle, moment.

Other supporting roles – with long-established Boston actors Remo Airaldi as the evil Antonio and Maurice Emanuel Parent as his accomplice Sebastian get less airtime but they execute them well.

As Ariel, John Lam has a bit more of a balletic approach that makes him seem a little more like Tinkerbelle than the more traditionally witty interlocutor of Prospero, but it might well be the textual trimming for the current outdoor pandemic production that makes his role seem a bit more slight than it frequently otherwise appears.

Why the originally male Gonzalo is transformed into a female role, as Gonzala (Siobhan Juanita Brown), is not too clear, though it balances out the sexual distribution of the cast a bit.

All in all, the production, well engineered by CSC artistic director Steven Maler, comes off beautifully in its conciseness.

– BADMan (aka Charles Munitz)

Leave a Reply