Film (2019)

Documentary

Directed by Amy Geller, Gerald Peary

Screenplay by Gerald Peary

Cinematographer and Co-Editor: David Reeder

Co-editor: Lucia Small

Composer: Rob Jaret

Film site, with schedule of virtual screenings

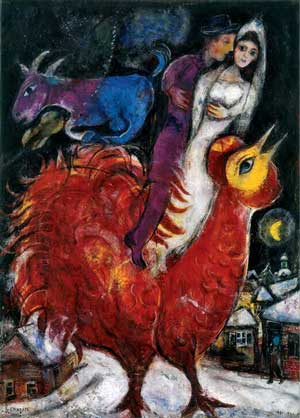

“Bride and Groom on Cock” (1947)

marcchagall.net

Rabbi Chaim Bruk and his wife Chavie Bruk are now middle-aged, have many children, and live in Montana. They went there about fifteen years ago as members of Chabad, an organization that is part of the Hasidic Lubavitcher sect based in Brooklyn and which devotes itself to reaching Jews throughout the world who it feels have, to one extent or another, abandoned their faith.

“We’re not missionaries,” declares Rabbi Bruk in this engaging film, forcefully, eloquently and with appealing conviction. “Judaism is not a missionary religion. We just help Jews to rediscover their Judaism.”

Inspired by the straightforward but challenging task to put a “kosher mezuzah” (a small, usually oblong, container with some prayers inside) on the doorpost of the dwelling of every Jew in Montana, Rabbi Bruk and his wife made their way West those many years ago, took up residence in Montana, and have made it their home since.

Remarkably, Rabbi Bruk’s endeavor in Montana is self-funding, not sponsored financially from the Chabad home office. One might think this unusual in a place not known for its abundance of Jews, but somehow, with verve, charm, determination and a pure sense of mission, Chaim and Chavie Bruk have created a small, unexpected success story.

This appealing and informative film, artfully put together by filmmakers Amy Geller and Gerald Peary, features the Bruks’ story, but, in an interesting and balanced way, and posits it within the context of the world of Montana’s small but surprisingly active and compellingly diverse population of Jews.

Featured at one point is an interchange between Rabbi Bruk and Rabbi Ed Stafman, a Reform rabbi with a very different outlook. Both charming and charismatic, Rabbis Chaim and Ed go at it in a debate about, essentially, the veracity of biblical narrative. For Rabbi Bruk, the Torah (the Five Books of Moses) makes no sense if it is not clearly historical. For him, there was, naturally and realistically, a Moses, an Exodus, a Golden Calf, and all the rest. Not only are the tales about them vivid and rich, but they are, for Rabbi Bruk, accounts of the way things actually happened. For Rabbi Stafman, the stories are indeed rich and significant, but the historic status of these tales is to be significantly interpreted and understood as part of a scriptural narrative that is at the very least a complex and heavily embellished version of the events in history that inspired them.

In the larger context of this largely heartwarming film which paints such an appealingly vivid picture of the Bruks, this interchange represents a wonderfully revealing moment. Through this exchange, one gets a sense of what lies behind the Bruks’ fervor and of the apparent straightforwardness and simplicity of the beliefs which inspire their endearing bearing and way of life. By providing the viewer this transitional opportunity to recognize the potency of such straightforward belief, the film enables one to take a breath and reflect on the benefits, and indeed some of the limitations, of an Orthodox perspective of this sort.

Nonetheless, this is done in such a delicately balanced and interesting way in the film that, though it makes one recognize this very traditional feature of the Bruks’ beliefs and how those inspire their actions, it does not judge them harshly for it, deposit them in a negatively charged box, nor draw away from a portrait of their considerable charms.

Though the Bruks are Chabadniks, the film is specifically about the Bruks and their endeavors in Montana and how they interact with other Jewish communities there. It does not give a detailed background about Chabad itself, but it may be useful, though not strictly necessary, for viewers of the film to know a little about Chabad and Lubavitcher Hasidism and its general place in the world of Jewish culture and religion, to get a sense of where the Bruks are coming from.

“The Praying Jew” (1923)

marcchagall.net

Hasidism (derived from the Hebrew hasidut, meaning piety) began in the mid-eighteenth century, inspired by Polish Rabbi Yehuda Ben Eliezer who gained the honorific The Baal Shem Tov (Master of the Good Name). It was a revitalization movement which brought a new kind of fervor and intensity to what had become a strongly sedate and scholastic trend in Jewish circles in Eastern Europe. With a particular devotion to Kabbalah, an embracing term for movements which comprise the Jewish mystical tradition, the Hasidim (followers of Hasidism) expressed their immediate sense of religious experience with joyful dancing, singing, energetic prayer, and other forms of kinetic observance which emphasized an experiential, rather than just an ideational, connection to God.

Many sects of Hasidism have developed in the past few centuries, and frequently each is aligned with a particular Rebbe or charismatic religious leader. For the Lubavitcher Hasidim, that Rebbe, in recent memory, was Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who died in 1994 but who, in the views of many Lubavitcher Hasidim, is still regarded as having been a living manifestation of the Messiah.

Chabad, often used interchangeably with Lubavitcher, is an evocative acronym formed by the first letters of the words Chochmah (wisdom), Binah (understanding) and Da’at (knowledge), three central images from Kabbalah. Interestingly, these component images seem, on their face, to represent an emphasis on the ideational and conceptual, though, in fact, the import, in the Hasidic context particularly, carries a strong vital and visceral sense. Lubavitcher simply is a geographic designation representing the town in Russia, Lubavitch, in which the movement began. (The meaning, in Russian, of Lubavitch, curiously, is city of brotherly love, but that significance is incidental to the Hasidic Lubavitcher movement.)

The Hasidic world as a whole is complicated, the number of its varied sects is large, and their relations are often strained. For those who may have watched Unorthodox on Netflix recently about a woman who left her sect in Brooklyn for a secular life in Berlin, the sect in question in that film was the Satmar, quite distinct from the Lubavitcher and often at serious odds with it.

In any case, the Chabad-Lubavitchers are very devoted to outreach and have set up centers around the world. One may often find them seeking out Jews in various locations to perform rituals of one sort or another as a way of drawing them back into the fold. They might be found on college campuses giving out menorahs at the time of Chanukah, or approaching men on line at Jewish restaurants in cities around the globe to see if they had yet put on tefillin (prayer boxes attached to the head and arms with leather straps) as part of their daily ritual. The Lubavitcher, in a word, are not shy about trying to help ritually inactive Jews to get more deeply involved.

To hear Rabbi Bruk talk about his sense of mission in this regard is infectious and inspiring, even if one has no involvement with or attraction to Orthodox Judaism. One automatically senses his deep belief in what he’s doing and feels a positive rapport with his unbridled enthusiasm. The film does not shirk from conveying that sense, while demonstrating the elements of Bruk’s belief system which provide this energy.

from “The Rabbi Goes West”

One of the truly endearing parts of the film is its evocation of the relationship between Chaim and Chavie Bruk and their devotion to family. As the Bruks detail openly, they were not able to have biological children, so they decided to adopt, and did so with abandon. The film depicts Chaim and Chavi with their six children to whom they are powerfully devoted, and to whom they have transmitted the full implications of their religious devotion. At least one of the children is African-American, which contributes a powerful sense of the support for diversity and inclusiveness practiced by this religious Jewish family living in the American heartland. It is endearing and powerful to hear Chaim and Chavie talk about their love for Montana which has developed during their time there. The sense, conveyed artfully and implicitly by the filmmakers, is that religious and cultural diversity can occur curiously and happily in many places, often unexpected ones, and that the key to its success is charm, charisma, and the desire for connection.

Indeed, the power of this film lies as much in its subtlety of presentation as in its declarations. The Bruks’ religious fervor is clear, but one remains in some suspense, throughout the film, about how these religious Jews will make it in Montana. And the denouement is that their mutual sense of mission, and, in some ways, its simplicity, gives power and significance to that effort. The filmmakers don’t bang one over the head with that message, but let it develop with a kind of organic flair, which makes it comes across all the more powerfully.

This is not a “talking heads” documentary meant to deliver all kinds of relevant information about the obvious subjects at hand. If there are talking-head moments, it’s with the Bruks themselves or with Jewish Montanans whom they have influenced or inspired, or with other Jewish leaders with whom they have interacted. But those moments feel like a continuing elaboration on an interesting portrayal rather than a deliberate and analytical treatment.

from “The Rabbi Goes West”

In an online Q&A with the filmmakers and with the Bruks, filmmaker Gerald Peary said that he was inspired to make the film in a quite straightforward way. Peary had heard about some rabbi in Montana who wanted to put a mezuzah on every Jewish doorpost and he wanted to investigate. And so he, and Amy Geller, with whom Peary eventually co-directed the film, did so. According to Geller, the narrative developed over time, as they visited Montana, filmed, came back East to edit and review, and then returned multiple times to follow up with more filming. The result has a kind of evolutionary flavor, with a message that grows out of its evolutionary strands and associated reconsiderations. Raising many questions, offering insights but no particular conclusions, the film is not so much declarative as exploratory, and in that regard feels like an anthropological adventure story.

In the Q&A, the Bruks expressed their extreme appreciation for the balanced quality of the film. Chaim Bruk said he thought it was the best film made about religious Judaism – fair, thoughtful, not deeply critical or vindictive. And when he acknowledged that the film does ask questions, as with the charged interchange between himself and Rabbi Stafman, it does so with an open mind.

Relatively brief, at 1h 13m, the film feels very full – of interesting and compelling personalities and their relations, of curious geography, and of the unexpectedness of its narrative. The filmmakers have periodic online screening runs. To find out about upcoming opportunities for viewing this engaging documentary check out the film’s website.

– BADMan (aka Charles Munitz)

Leave a Reply