Concert

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Andris Nelsons, Music Director

Tanglewood Music Center

Lenox, MA

Saturday, August 25, 2018, 8pm

Conductors: Andris Nelsons, Christoph Eschenbach, Keith Lockhart, Michael Tilson Thomas, John Williams

Host: Audra McDonald

With Midori, violin; Yo-Yo Ma, cello; Kian Soltani, cello; Jessica Zhou, harp; Nadine Sierra, soprano; Susan Graham, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Hampson, baritone; James Darrah, stage direction; Joshua Bergasse, choreography

Additional vocalists: Isabel Leonard, Jessica Vosk, Tony Yazbeck, Clyde Alves, DJ Petrosino, Ryan Ghysels, Christopher Rice, Alex Ringler, Clay Thomson, Mikey Winslow

Tanglewood Festival Chorus: James Burton, conductor

Overture to Candide

Andris Nelsons, Conductor

Leonard Bernstein

First movement, Phaedrus; Pausanias (Lento-Allegro) from Serenade (after Plato’s ‘Symposium’) for violin and orchestra

Midori, violin

Christoph Eschenbach, conductor

Leonard Bernstein

Kaddish 2 from Symphony No. 3, ‘Kaddish’

Nadine Sierra, soprano

Women of the Tanglewood Festival Chorus

Keith Lockhart, conductor

Leonard Bernstein

Meditation No. 3 for cello and orchestra, from Mass

Kian Soltani, cello

Christoph Eschenbach, conductor

Leonard Bernstein

Selections from West Side Story

Isabel Leonard (Maria), Jessica Vosk (Anita), Tony Yazbeck (Tony), Clyde Alves (Riff), DJ Petrosino (Bernardo)

Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor

Gustav Mahler

Der Schildwache Nachtlied from Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Thomas Hampson, baritone

Andris Nelsons, conductor

Aaron Copland

Finale of Appalachian Spring

Michael Tilson Thomas, conductor

John Williams

Highwood’s Ghost

Jessica Zhou, harp

Yo-Yo Ma, cello

John Williams, conductor

Gustav Mahler

Finale from Symphony No. 2, ‘Resurrection’

Nadine Sierra, soprano

Susan Graham, mezzo=-soprano

Tanglewood Festival Chorus

Andris Nelsons, conductor

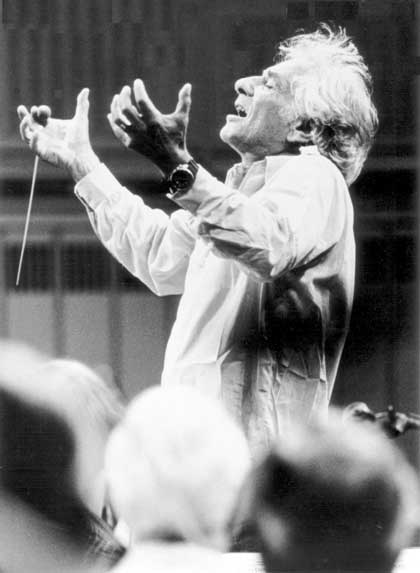

Photo: Courtesy of Brandeis University

There is almost no way to do justice in a single concert to the passion, energy, creativity, complexity and influence of the great American maestro and composer Leonard Bernstein (1918 – 1990), who was born exactly one hundred years ago. There is also almost no way to imagine Lenny – as he is so fondly referred to by many colleagues and scions, including those who knew him well and those who were just influenced and inspired by him – as an old man. So eternally vital, even seemingly so in his final stages of life, Bernstein evoked youth and vivacity itself.

This concert, bejewelled by stars from every corner of the musical universe, adeptly did what it seems intended to do – to raise a symbolic glass to the great maestro and do it with beautifully rendered musical quotations from both Bernstein’s own corpus and from some of the works of other composers that evoke a sense of Bernstein’s passion, innovation, influence and spirit.

The selection of works was a combination that had some of the expected elements, while some of it was idiosyncratic. The contrast was quite appropriate for a tribute to Bernstein who, in one sense, was a popularist, and, in another, private and complex both in sensibility and in aspiration.

Almost by necessity of appropriateness, the ripping and gleeful overture to Candide opened the program. This complex filigree of humourously and whimsically sentimental themes leaps off the stage, and the Boston Symphony, in Andris Nelsons’ adept hands, enabled it to do so with panache. Since taking the podium of the BSO several years ago, Nelsons has made his own daring adjustments, moving from more cautiously calculative to more outlandishly passionate and the results have been most welcome. Here, in Candide, he shows both strengths with the capacity to direct the maelstrom of intricately interlocking phrases that come together in a sweet broad musical joke. The BSO and Nelsons delivered, kicking the musical ball well down the field for the opening of a wonderful, often exuberant, concert.

Moments of reflective charm, exhibitive of Bernstein’s lurking, lingering and often self-perceived unfulfilled capacity to deliver on his more serious works, surfaced in multiple places. The first movement of Phaedrus; Pausanias (Lento-Allegro) from Serenade (after Plato’s ‘Symposium’) was such an instance. Soloist Midori offered a searching and plaintive account that had an occasional glimmer of what we think of as Bersteinesque verve, but was mostly calm and reflective. It’s odd, in some ways, that Bernstein chose such a sober approach to Plato’s Symposium, which is one of the great philosopher’s most robust, and, in many ways, hilarious dialogues. Hidden in the text, however, is Pausanias’ justification of homoeroticism, which may well have been Bernstein’s inspiration. Taking it as a solemn avowal of sexual proclivity may have been his angle, which well could have served to deliver the prevailing sober and earnest tone.

Kaddish 2 from Bernstein’s Symphony No 3, ‘Kaddish’ was sung by soprano Nadine Sierra, with Keith Lockhart conducting. Again, this is a sober and reflective account, thoughtfully rendered and evocative of Bernstein’s longing for a sense of confirmation not only of spiritual affirmation in the face of death, but for a sense of affirmation of his deepest musical passions.

Meditation No 3 for cello and orchestra from Bernstein’s Mass, played with verve, precision and an excitingly nuanced athleticism by the young cellist Kian Soltani, trod more visibly on the realm in which Bernstein had some of his greatest meldings of thematic and reflective invention. Mass, of course, is a kind of robust staged oratorio, with many playful elements melded into deeply reflective ones. But the overall timbre of the piece is, much like the musicals for which Bernstein is so fondly acclaimed, theatrical. Bernstein’s adaptation of the Meditations from Mass for cello and orchestra is a distillation of the musical grandeur embedded in Mass and gives it a poignancy and eloquence that rises out of that theatrical context. Soltani gave it an exquisite reading, eloquent, agile, suggestive in its dances around the fingerboard, but pitched in its yearning. Christoph Eschenbach offered a measured and careful guidance to the orchestra which filled the landscape behind Soltani’s quiverings while not overwhelming them.

Full Circle: Leonard Bernstein and Tanglewood, a sweet film about Bernstein’s history at Tanglewood since his early days studying there with Serge Koussevitsky, was a lovely evocation of context, place and personality. As the film exhibited so well, Bernstein brought Tanglewood alive when he arrived through its gates, and it seems fully appropriate that the place of this centennial celebration be at Tanglewood.

with Michael Tilson Thomas and the BSO at Tanglewood

Photo: Hilary Scott

Courtesy of Boston Symphony Orchestra

Concluding the first part of the program with works authored by Bernstein, was a terrific account from West Side Story. Excellent choreography accompanied the already exquisite music. A combined cast of musical theater, and opera, professionals made for a memorably amalgamated rendition.

Clyde Alves, as Riff, was just what the doctor ordered – sassy, nasty, energetic, full of zip. (Earlier in the summer I saw Alves as the lead in Ogunquit Playhouse’s An American in Paris, in which he did a terrific job.)

With a heartstoppingly resounding mezzo-soprano, the young Met star, Isabel Leonard, stole hearts and took away a few breaths, as Maria. Her voluptuous voice is accompanied by a true actor’s sensibility. She is so good in this role that one wonders why she isn’t moonlighting on Broadway. She certainly has the theatrical chops to stir the pot downtown; she was ascendant in this performance. Tony Yazbeck, as Tony, offered a lovely, adeptly clambering, tenor always reaching higher with elevated tonal grandeur.

Overall, it was, as one would expect, a gripping way to end the first half of this momentous show, delivering in exquisite style some of what Bernstein, in some ways despite himself, did the best.

The second part of the program was entirely non-Bernstein as far as composition went, but very Bernstein in terms of inspiration and influence.

Two of those slots, including the finale, were, not surprisingly, by Mahler. Bernstein was deservedly famous for his authoritative recordings of the complete Mahler symphonies for which, in many ways, he was the earliest and most significant proponent.

The first piece, Der Schildwachs Nacthtiled from Des Kneben Wunderhorn featured the noted baritone Thomas Hampson invoking the grimly difficult lyrics of The Sentry’s Night Song from the folk collection of which it is a part. I cannot and will not be cheerful while others sleep, begins the poem, a clear testament to the restive, demanding, fully-charged and anti-gravitational maestro who seemed to make it his business to exuberate in order to allow others to do so.

Preceding the final were the Finale from Copland’s Appalachian Spring, a tribute to the sense of Americana that Aaron and Lenny, the two Jewish-American musical geniuses and great friends, shared.

Photo: Hilary Scott

Courtesy of Boston Symphony Orchestra

The original piece on the program, John Williams’ Highwood’s Ghost, was conducted by the composer. Jessica Zhou, on harp, and Yo-Yo Ma, on cello, executed it with precision and verve. Highwood House, on the Tanglewood campus, is reputed to be spooked and this piece of Tanglewoodiana gave rise to Wiliams’ invention. More as a place-oriented tribute in honor of Lenny rather than an evocation of Bernstein’s ghost, the piece did its work, bringing out the precise magic of Zhou’s remarkable polyphonal pickings, and Yo-Yo Ma’s invariably wonderful stylistic presence. A spookily meandering atmosphere piece, Highwood’s Ghost brings to mind the background themes of much of Williams’ film music without too much of its dominant melodic inspirations. One might think of it as a popular companion to some of Bernstein’s less dramatic works from the first half of the program, serving as a frame, rather than a portrait, of the centennialized protagonist.

Photo by Paul de Heuck, courtesy of The Leonard Bernstein Office, Inc.

The Finale from Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, the ‘Resurrection’, with Nadine Sierra returning to sing soprano, the notable mezzo Susan Graham, and the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, brought out the spirit of Lenny’s constancy, his return in transcendent echoes throughout Tanglewood, and indeed throughout the musical world. With Mahler’s embedded passion, religiosity, earnestness and sense of drive and aspiration, and the symphony’s theme of redemption, it provided an appropriately grand and reflective closing.

But all was not quite closed. The program, introduced at various points by the unlimitedly charming Audra McDonald, who delivered exquisite tributes to Lenny penned by Stephen Wadsworth, now came out, in the final moments to sing. The rumbling undertones of the concert always alluded to the current political scene, and this moment was no exception. With resonance and verve, McDonald led the entire cast of featured soloists in a rendition of Somewhere from West Side Story. It was resounding, it was heartbreaking, it was just as Lenny would have loved to have had it.

at Tanglewood

Photo: Hilary Scott

Courtesy of Boston Symphony Orchestra

– BADMan

Leave a Reply