Film (2016)

Documentary

Directed by Steven Okazaki

Written by Stuart Galbraith IV and Steven Okazaki

Narrated by Keanu Reeves

Film Editing by Steven Okazaki

With Wataru Akashi, Kyôko Kagawa, Takeshi Katô, Hisao Kurosawa, Shirô Mifune, Toshirô Mifune (archive footage), Haruo Nakajima, Sadao Nakajima, Yôsuke Natsuki, Terumi Niki, Teruyo Nogami, Tadao Sato, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Yôko Tsukasa, Kanzô Uni, Kaoru Yachigusa, Kôji Yakusho

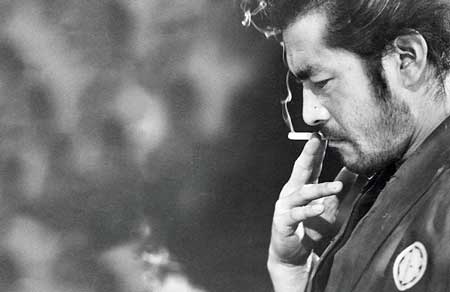

in “Yojimbo”

It is hard to imagine contemporary Japanese cinema without Toshiro Mifune, the star of many great films and a long-time collaborator with the noted Japanese director Akiru Kurosawa. The Kurosawa dramatic classics Rashomon (1950) and The Seven Samurai (1954) both feature Mifune, as does the later, lighter, Yojimbo (1961).

Mifune’s work is exquisite throughout and this documentary goes a long way to demonstrate how that is the case. Nobody, including the series of colleagues who recall Mifune, knows how to account for his greatness, though they all acknowledge its presence. Like Brando, there was a certain intensity to Mifune’s performances; he was incredibly versatile as well. An accomplished comedic actor, Mifune could light up the screen with his shenanigans at the same time that he could alarm and arrest it with his magnetism.

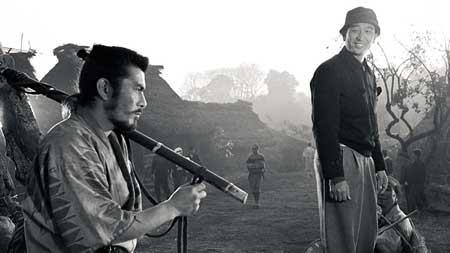

Apparently Kurowsawa had such respect for Mifune’s capacities as an actor he did not seek to direct him in enormous detail. Fellow actors recall the control and the organization on Kurosawa’s set, but they also recall the way in which Mifune apparently would take flight during filming and do things unpredictably, which seemed to be fine, oddly enough, with the otherwise meticulous Kurosawa.

Because of Kurosawa’s and Mifune’s long and close partnership, this documentary is also, in great part, about Kurosawa, even though the focus is specifically on Mifune. Both dead, neither weighs in directly through interviews, but there are plenty of insights offered by Mifune’s son, Kurosawa’s son, and by actors who worked with them both. American directors Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese also weigh in significantly throughout. Many of these interviews are remarkably penetrating, revealing and touching.

with Director Akira Kurosawa

on the set of

“The Seven Samurai”

Interesting facts come to light.

Mifune did not originally seek to be an actor; rather, he wanted to be on the production end, involved with filming itself. When some sort of opportunity came up to see how one might do in front of the camera, he took it, was selected, and quickly became successful enough that he gave up the idea of being involved with film production itself.

At a point well on in their careers, Mifune and Kurosawa stopped making films together; the reason is not entirely clear. Mifune went on to make some films under Western directors.

He was, believe it or not, offered the role of Obiwan Kenobe for the original Star Wars film by George Lucas but was advised by his American agent, unbelievably as well, not to take it. Alec Guinness wound up being great in that role, but how interesting and different it would have been with Mifune, a seasoned Samurai actor, in his place.

Kurosawa had a series of failures after his breakup with Mifune. Despair settled in, for Kurosawa, and he made an unsuccessful suicide attempt. He was rescued, oddly enough and interestingly, by two young American directorial disciples, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, who helped him reignite his career with Kagemusha (1980), his version of King Lear, which was a great cinematic success.

The portrait of Mifune rendered in this film is penetrating and moving. He was a consummate actor with a wild and energetic talent. He was a hard and determined student of drama and a complex and, in some ways, difficult person. He loved cars and alcohol, frequently together, an emblem of a wild life. The film notes, but doesn’t overplay, that dimension; it alludes to it deftly. Describing both the havoc he wreaked on his family life and the touching connections he continued, despite that, with his wife and son, the film gives a nuanced depiction. Evoking the dramatic pizzazz of this great actor, this documentary gives a sense of shimmering talent without itself being melodramatic. It is a beautiful, fascinating, touching, subtly constructed tribute to one of the cinematic greats of the second half of the twentieth century.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply