Opera (1896)

Music by Giacomo Puccini

Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa

Based on Scènes de la vie de bohème (1851) by Henri Murger

Conducted by David Angus

Boston Lyric Opera

Citi Shubert Theatre

Theater District, Boston

October 2-11, 2015

With Kelly Kaduce (Mimi), Jesus Garcia (Rodolfo), Jonathan Beyer (Marcello), Emily Birsan (Musetta), Brandon Cedel (Colline), Andrew Garland (Schaunard), James Maddalena (Benoit, Alcindoro)

Jesus Garcia as Rodolfo

in “La Bohème”

Photo: T. Charles Erickson

Courtesy of Boston Lyric Opera

In the original, the group of artists and poets who inhabit this tale of love and woe live in the Latin Quarter in the Paris of the 1840s, alienated, in general, from the bourgeoisie, but not in obvious political rebellion against them.

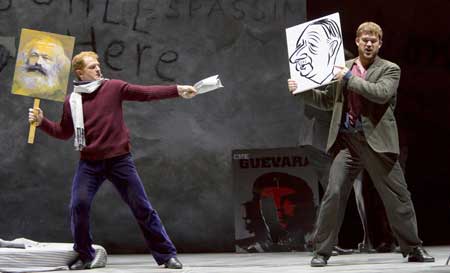

Here, the stage has been reset in the midst of the great social upheavals of 1968, with the group of artists and poets meandering around the barricades and inhabiting spaces adorned with posters of Che Guevara and Jean-Luc Godard. It’s an interesting alteration that works in some ways, not in others, but ultimately serves to add a bit of lively contemporary cultural color to Puccini’s immortal score.

Kelly Kaduce as Mimi

in “La Bohème”

Photo: T. Charles Erickson

Courtesy of Boston Lyric Opera

Wherever it’s set, the story about the love affair between Rodolfo, a poet, and Mimi, a girl who makes decorative flowers to sell, and their social set, remains the same. Lyrics get a little changed up to accommodate the shift of times, but, otherwise, the narrative follows the same lines.

Basically, Rodolfo and Mimi meet by chance, they fall in love, they separate and then they come together again just as Mimi is about to die. Embellishing the story is a lively romance between Rodolfo’s roommate Marcello, a painter, and Musetta, a live-wire with whom he shares love and mutual torment. They’re also on hand to support the story when Mimi’s illness gets critical.

The big cause of the separation between Rodolfo and Mimi is his irrational jealousy. It’s an odd and not very convincing narrative turn, but it provides the basic thematic shape for love found, lost and regained that the dramatic music requires. The jealousy gambit does not really carry thematic weight, and one is tempted to stand back and suggest that Rodolfo get himself to a shrink as quickly as possible. That, however, would make operetta out of grand opera, so it might be best, in the interest of this great and grand opera, to scratch that idea.

Kelly Kaduce as Mimi

in “La Bohème”

Photo: T. Charles Erickson

Courtesy of Boston Lyric Opera

However you regard the story, which is, indeed, minimal, the music is just out of this world. One hit aria follows another, many of them plaintive and poignant, and in between those are walls of music and choral support that are vivid and musically satisfying.

One hears throughout La Bohème‘s score some of the Japanese style touches that flavored European art at the end of the nineteenth century – Monet and Van Gogh were certainly affected by those – and that very much made sense when Puccini went to compose Madama Butterfly in 1904. In La Bohème, the effect is slightly otherworldly, haunting and exotic. Combined with the flavor of otherness that the off-the-grid Bohemians exhibit, the music colors a landscape in which the deep cultural morphing of these Bohemian cultural rebels flourishes.

The current production makes an interesting effort to add narrative dimension by resetting the story amid the political turmoil of the late 1960s, but, apart from the curiosity and the stimulating additions in the production that result, the choice seems a bit off.

“La Bohème” (1896)

by Adolfo Hohenstein

Rent (1994), the musical theater adaptation of La Bohème by the late Jonathan Larson which went on to enormous success on Broadway, got the social transposition more correct. Setting the Bohemians in the Lower East Side of the 1980s during the height of the AIDS epidemic fit right in with the gestalt of La Bohème. The setting was not particularly political, but socially alienated nonetheless, and the overarching health crisis paralleled the threat of tuberculosis that became the nemesis of Mimi in the original setting.

Making the setting highly political in the current production gives a sense of heightened drama to the context of the story, but does not make much sense for the characters, who are artists and hippies, not politicos. So, there is something conceptually a bit off in this production’s orientation. It feels oddly like a combination of Rent and the Broadway version of Les Misérables in which rebel politics of the 1830s in France figure centrally. In the stage version of Les Miz, an onstage barricade is a focal feature, which the current production of La Bohème adopts as one of its main motifs as well. The similarity is striking and does not make much sense.

That being said, the production is beautifully designed, lighted and directed. The way in which projected videos and stills are used in recollection of 1968 is stirring and effective, even though its application may not be quite right. And, as with most of the BLO productions from recent years, a great deal is very effectively done with relatively little matériel onstage.

Arturo Toscanini

conductor of the premiere of “La Bohème”

The singing, overall, is quite good.

The real standout is Jesus Garcia as Rodolfo, who has a finely shaped tenor, clear and bell-like, penetrating without being piercing, his lines streamlined and full. At the end, the audience rose with special appreciation for his performance.

Kelly Kaduce as Mimi is fine throughout, but gets richer, fuller, and more convincing near the end. Her final arias are wonderfully deep, rich and resilient.

Brandon Cedel as Colline

in “La Bohème”

Photo: T. Charles Erickson

Courtesy of Boston Lyric Opera

Brandon Cedel as Colline does not have a major part, but his baritone is vividly clear and forthcoming. The aria in the last act sung to his dear old coat which he has to pawn to help out Mimi was superbly moving.

The orchestra rendered the familiar, but moving, score adeptly, and conductor David Angus managed the intricate networks of choral and solo interleavings adeptly.

Though the setting may not make total sense, the production is visually interesting and well carried off and conveys the force of the music and drama a bid oddly but effectively.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply