Play (1901)

by Anton Chekhov

Translated by Paul Schmidt

Directed by Mara Rainer

Wellesley Summer Theatre

Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA

May 21 – June 21, 2015

With Angela Bilkić (Másha), Zena Chatila (Ir´i;na), Caitlin Graham (Ólga), Samuel L. Warton (Andréi Sergeyevitch Prózorov), Woody Gaul (Vershínin), Charles Linshaw (Baron Túzenbach), Marge Dunn (Natásha), Shelley Bolman (Kul´y;gin), Daniel Boudreau (Solyóny), John Kinsherf (Chebutýkin), Zach Georgian (Fedótik), Dan Prior (Róhde), John Davin (Ferapónt), Charlotte Peed (Anfísa)

Zena Chatila as Irina

Caitlin Graham as Olga

in “Three Sisters”

Photo: David Brooks Andrews

Courtesy of Wellesley Summer Theater

One of Chekhov’s greats, Three Sisters weaves a tale of disappointments, but does it so artfully that the cumulative effect has a poetic satisfaction that rises above them. One watches ruefully as love’s disappointments unfold, but is ultimately bolstered, in a strange way, by a deepened sensitivity to, and understanding of, the subtleties of choice and disposition that cause those disappointments.

This production, interestingly and compellingly, begins and ends with a line dance.

At the outset, the actors enter slowly, rhythmically, hand in hand, bound to one another, moving forward gradually into the scene of the action, while Zena Chatila (Irína), sweetly sings Dink’s Song: If I had wings, fare thee well oh honey, fare thee well. This song of lost love, first recorded as sung by an African-American woman (named Dink) in 1909, is a hypnotic and engaging opening, an interesting application of a traditional American folk song upon a setting involving Russian gentry and soldiers at roughly the same historic time. It works, and serves to introduce the sense of a string of characters deeply bound to one another facing the hopes and losses of love and of the poignant meanings it brings.

The end of the play sees the cast exit, without the folk song, but equally compellingly.

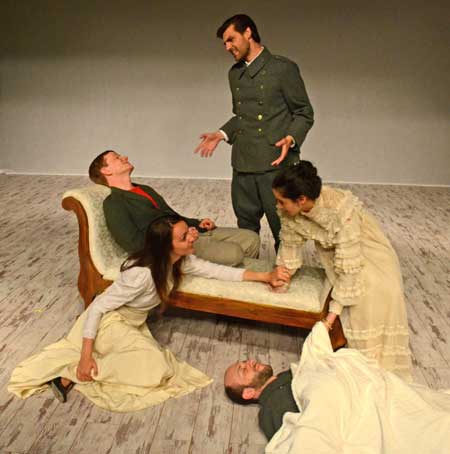

Shelley Bolman as Kulygin

Woody Gaul as Vershinin

Zena Chatila as Irina

Charles Linshaw as Baron Tuzenbach

in “Three Sisters”

Photo: Courtesy of Wellesley Summer Theatre

The three sisters – Ólga, Másha and Irína – are equally unhappy for different reasons.

Ólga is unmarried, though she would have liked to have been. Másha is married to the older schoolteacher Kulýgin who is a decent fellow and loving husband, but by whom she is now, six years into marriage, bored. And Irína is pursued by Baron Túzenbach, who she finds pleasant but whom she does not love. Másha finds herself intrigued, and then captivated by Lieutenant Colonel Vershínin, who is in town with the regiment. But he is married to an unstable woman and father, with her, of two children.

The brother of the three sisters, Andréi, also has his miseries. A promising career is foreshortened by an unfortunate marriage to Natásha who subsequently dominates and then betrays him. And, to add insult to injury, an older family friend, Chebutýkin, putatively an army doctor, provides a warm avuncular presence until his miseries, exhibited through his drunkenness, get in the way.

And this is only the setup. Various other entrancements, disappointments and tragedies follow, leading to a prevailing sense of emotional cataclysm.

Chekhov’s great talent as a dramatist provides complex situations which hover on the border between comedy and tragedy. He depicts characters who suffer, but frequently because of their own misapplications of judgment. Fateful disappointments enter into the equation often as the fruition of unfortunate seeds. A poorly or randomly selected marriage, in this play, spells fate for all of the participants. The longing that provides the emotional meat of the drama is that which appears after the fateful seeds have been sown, emblematic of that gradual enveloping of disappointments.

Angela Bilkic as Másha

in “Three Sisters”

Photo: Courtesy of Wellesley Summer Theatre

The setting is a country town where this group of somewhat landed gentry suffer from boredom and muse on the possibilities of work. Not exactly needing it, but wanting it in some way, the lines I never worked a day in my life, but I intend to work, and In twenty-five or thirty years we will all work carry a sad truth, looking backwards, at the turn of the twentieth century to the rotting class divisions of the previous centuries, and foreshadowing the explosions of class revolution to appear in Russia over the next twenty years.

The great virtue of this lovely, intimate production is that it gives a vivid sense of this knotted working of fate, as though under a magnifying glass, up close. One barely thinks of the actors as upon a stage, more as though one is sitting in the living room amid them, witnessing their hopes and sufferings at arm’s length.

The fine cast here has experience that ranges across the board. Zena Chatila, who plays Irína and who sings that wonderful account of Dink’s Song at the opening, is an undergraduate, as is Zack Georgian who plays Fedótik. Other of the actors are professionals, and the combination works very nicely.

The role of Másha in this play is typically regarded as the meatiest and Angela Bilkić does it justice. Her nuanced expressions of mood, enchantment, disappointment, frustration travel across her face with subtle transitions, conveying an overall sense of a passionate and vital character constrained by life choices. The writing of the play makes Másha a more anger-prone character than one might expect from her otherwise noble demeanor, which provides particular challenges to this role. While at some times rising up with an admirably defiant resilience, she, at other times, snaps and quibbles. Chekhov, surely meant to bring out both sides of a noble yet frustrated character, but the combination, in a role that has many of the traits of a tragic heroine, is more emotionally complex than that. Bilkić does a good job of conveying that resilient but troubled passion which carries the heroic character of the role through its more annoyed expressions.

Vershínin, the lieutentant colonel and Másha’s married love interest, is the play’s philosopher, expressing, in a series of semi-monologues, a sense of fragility of time and its impact on social relations. No one will remember – that’s true, he says, and, in declaiming that, along with an otherwise optimistically tinged stoicism, captivates Másha’s heart. Woody Gaul gives Vershínin a respectfully plaintive quality that demonstrates, appropriately, the subtlety of his appeal to the broodingly passionate Másha.

in the original (1901)

Moscow Arts Theatre production

of “Three Sisters”

The networks of expectations and disappointments that weave the web of this carefully wrought narrative are a kind of wonder to behold, and part of the odd pleasure, if one can call it that, of watching the play is to see how conjoined these disappointments become. At various points Kul´y;gin, Másha’s decent, older, cuckolded husband indicates to Olga, the oldest, unmarried sister who has desperately desired marriage but has been unable to attain it, that he might have as easily married her as Másha, who is unsatisfied with their union, but cannot escape it. It is an innocently presented but devastating revelation, beautifully characteristic of the Chekhovian turn, comic and tragic in one breath.

With the gestures of Chekhov’s pen, the terrible ironies abound, and this charming production gives a sense of the resultant aches articulately, vividly and intimately.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply