Film (2013)

Written and directed by John Maloof and Charlie Siskel

Music by J. Ralph

Cinematography by John Maloof

Film Editing by Aaron Wickenden

Kendall Square Cinema, Cambridge, MA

With John Maloof, Mary Ellen Mark, Phil Donahue, Vivian Maier

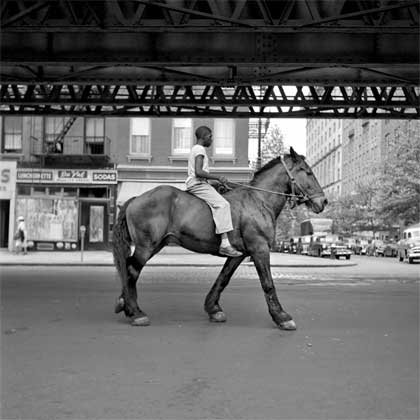

Still from “Finding Vivian Maier”

Photo: Vivian Maier

Courtesy of the Maloof Collection.

This documentary, by John Maloof, of his own discovery of the work of Vivian Maier, is fascinating, heartrending and full of ironic curiosities.

Some years back, Maloof essentially stumbled upon a box of slides that he began to peruse and was taken aback by their distinctive artistry. He only knew they were by someone named Vivian Maier, but did not have much of any kind of background information about her. Gradually, Maloof began to collect more of her work and to uncover more about her life.

Remarkably, Maier had taken something like 130,000 photos, some of which remained on rolls of undeveloped film that Maloof gradually began to process and print. Shockingly, none of her estimable work had been discovered or shown during her lifetime.

Still from “Finding Vivian Maier”

Photo: Vivian Maier

Courtesy of the Maloof Collection.

As the film documents, when Maloof began to call attention to Maier’s work, there was considerable interest in it. Accounts by art dealers of the enthusiastic response, and footage of heavily attended exhibitions of her work, testify to its immediate appeal.

Interspersed throughout the film, noted photographer Joel Meyerowitz weighs in to add his imprimatur, essentially dubbing her work as primary rather than derivative, offering quite significant critical recognition.

As Maloof’s film shows, Maier’s work life was almost entirely unconnected with her secretive artistic one. For most of her career, she was a live-in nanny for a sequence of families, some of whom are interviewed in the film. A fairly wide variety of impressions emerge, but generally convey the sense of someone quite private and quite odd. When difficult memories of Maier surface, Maloof does not hesitate to keep his lens focused.

At once, this is an interesting study of artistic archaeology and artistic character.

Underlying the archaeological tale is the recognition that had Maloof not looked at that initial tray of slides and had he not pursued her other work, all of this might have been thrown in a dumpster and lost to history. One can only think, in parallel, of the case of Emily Dickinson, who wrote her poems and stuffed them in a drawer. If her sister, Lavinia, had not sought to publish them after her death, they too might well have been lost. At least Dickinson had family who survived her and knew something of her work. Maier appears to have been quite alone in the world.

It is also a remarkable study in artistic temperament and a testament to the sometimes inconsistent mix between confidence of artistic vision and lack of it in artistic self-promotion. As Maloof shows, there are only the smallest hints that Maier tried to publicize work. If she did, she did it hesitantly and inconsequentially. There is, in Maloof’s account, a kind of implicit sense of the tragic in Maier’s incapacity to somehow openly represent herself in the world through her art. The subtext of the film suggests that promotion of art is often as important to its recognition as is its quality, sometimes more so.

Still from “Finding Vivian Maier”

Photo: Vivian Maier

Courtesy of the Maloof Collection.

In some ways, Maloof’s film is itself a promotion for Vivian Maier’s work which he discovered and now represents. There is a curiosity in that fact and something which itself does not smack of artistic purity, but it seems the filmmaker-cum-promoter well understands that and pretty much continues to wink at the viewer about it.

At the same time, he and his co-creator, Charlie Siskel, have created a fine film, beautifully written and constructed, that tells a riveting and interesting tale about a shadowy and complex, but relentlessly fascinating, artist, and about the endlessly rich trove of her work which might very easily have been lost to history.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply