Poems

by Jamie Stern

Published January, 2013

by the Virtual Artists Collective

This delightful and touching collection of poems by New York based lawyer-poet Jamie Stern is a biography of sorts as well as a collection of pointed and carefully wrought lyrical pieces. The subject, by and large, is Stern’s grandmother and the subject is warmed by the aura of a granddaughter’s feeling as well as seasoned with the sometimes sharp spices of an unrelentingly honest artistic sensibility. The combination is a most interesting mixture, threatening, by its very subject-matter, to veer into sentimentality; yet, by virtue of the directness of the observations and the adroit technique Stern uses to shape her stanzas, it does not at all do so.

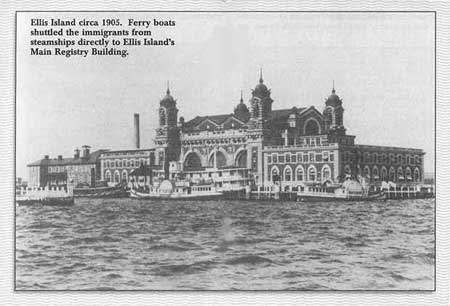

The portrait, in many ways, is heartbreaking. The tale of a difficult marriage between Stern’s grandparents creates a landscape which, in addition to the trials of Jewish immigrant life in early twentieth century New York, is full of fizzures, roadblocks and hovering calamities.

Though the collection is devoted to her grandmother’s story, the penultimate, fairly long, poem of the collection is dedicated to Stern’s mother, who died twenty some years before the poem was written. The sense I had from reading this tragic, but beautiful, ode was that the grandmother’s poetic biography was central to the creation of this – that to be able to fully understand her mother’s story Stern had to write her grandmother’s story as well. The relationship of Florence (Stern’s mother) to Esther (her grandmother) is the unspoken story here, but revealed, obliquely, through the captured moments of Esther’s life and the long, deep echo in the space left by Florence’s death.

Stern’s compact narratives often create charming domestic portraits that get beautifully capped with a line that sums and focuses the pictorial scene into a pointed sensible gesture.

The first poem in the collection, Esther’s Grinder, is a case in point. After describing the food grinder, how Esther sets it up, and the potatoes and onions that go through it, Stern positions grandmother and granddaughter opposite one another, “Until our eyes were level.” And, then, a deft final line, “Until her breath stopped at my cheek.” wonderfully gives the sense of intimacy and boundedness at the same time, the sensation of breath of another as close as it can be, yet aware of the spaces of age, history and experience between.

At the Dentist gives a lovely picture of an office visit at the dentist Esther shares with Zsa Zsa Gabor, with “perfume dabbed behind her ears,” beautifully encapsulated in Stern’s capsule phrase “a glimmer of glamour.” And the narrative denouement – with Stern, as a girl, encountering Zsa Zsa while Esther goes in to be treated, and getting an autograph dedicated to Esther, whose name Stern provides in place of her own – is dramatically dense and touching.

The deep family biography is inscribed by The Family Purchase which describes the coming together of Esther’s parents, Ida, “a girl with a broken nose” who “had limited prospects” and Alexander, who “fleeing the rabbinate… liked Ida’s family.” Again, in this brief, but unsettling and potent, biography, Stern ends with a compact phrase that seems to say it all: “He read when he wasn’t drinking/ and stayed out at night.” The poem ends there, a sepia portrait that, lifted close, delivers echoes of Talmudic tomes, brandy and emotional betrayal.

Bialystok: 1906, written about the pogrom in the year Esther was born, gives an adept historical summary portrait in a few phrases. “It started with a feast./A procession for the feast of Corpus Christi.” while “Axes, crowbars,/ slabs of iron” found their Jewish marks. In a pungent final couplet, noting the participation of police, Stern, with austere wit, observes “The police chief/ was promoted.”

In the piece that gives the book its title, Chasing Steam, Stern draws a portrait of Esther singing in the kitchen with her mother, “and the steam rising/ with the sweetish smell of cabbage/hung in the air, thick as cloud,” Esther jumping to catch it. This delightful domestic portrait from the old world has a whimsical and hopeful sense about it while, in historical and personal terms, it exhibits a kind of foreboding.

Stringing Stories captures Esther’s brother, Max, whose fanciful tales of the old country where “Everyone was Jewish. / There was no such thing as Jewish.” suggests the fantastical worlds drawn by Isaac Bashevis Singer in his tales, while, through that seemingly self-contradictory, but compact and adroit, phrase, uncovering the homogeneity of Jewish culture isolated within shtetls and ghettos.

What Hands Need tells cogently what, in the world of Esther’s rearing “The only girl” was expected to do – peeling potatoes and scrubbing. But her hands needed verse as well, so, in the distilled capping summary “Esther learned to scrub/ and silently recite.”

After several poems recounting the trials of World War One and Esther’s subsequent journey, in 1920, with her brother, to America, another short poem, also entitled What Hands Need, brings forth concise images of a new world: “Grapes in winter. Shuffled cards.” And, “Hiawatha.//Handlebars/ and/ the will to pedal.” fill out this line drawing so economically rendered.

The Landing: 1920 tells briefly and heroically of Ida’s separation from Alexander, “a husband whose eyes/ always looked elsewhere. Even at sea.” Despite her broken nose and the sense that this unsatisfying marriage was “Ida’s only hope,” “She left Alexander/ when she left the ship.// Her finest moment,” framing a moment of humble conquest with deserved grandeur.

A picture of a young woman taken by poetry then yields David: 1924, a short, dry emblem of the fateful meeting between Stern’s grandparents – “She could not have been looking./ She was eighteen./ She was reading Longfellow.”

Married gives a portrait of Esther and David surviving domesticity and as sympathetic a portrait of Dave as Stern can muster, noting that “Dave was always working. Lifting something heavy,/ pushing himself/ and the men on the floor,/ while his father read Hebrew,/ his brother became a doctor,/ his sisters married well.”

In a brief, cunningly adroit, scene, Stern, in Naming Rights: 1926 details the birth of her own mother, Florence, and the way that her mother got that name, forced upon her and upon Esther by Dave and his mother, despite Esther’s wish to call the girl “Helen.” “Rest, he said to Esther, firmly,/ handing Florence to the nurse.”

Gone Fishing shows a yelling, and perhaps hitting, Dave leaving for a fishing weekend “on the lake without them.” The combined final lines of the scene is chilling: “A still boat./ The chance to slit/ some trout’s throat.”

Prometheus in Rockefeller Center encapsulates the horrifying relationship Stern draws between Esther and Dave, moving from the Greek myth to the domestic tragedy with an adroit summary: “Prometheus in chains./ A vulture pecking at his liver./ Like Dave/ pecking at hers.” Ouch.

The Jello Mold draws a concise and hilarious portrait of a family dinner in which Esther’s son and his Catholic wife and children refuse the jello mold Esther has made, though her daughter and her Jewish family do eat it.

A Different David paints a beautiful, short portrait of another David than her husband, an ailing, but congenial, companion to her in old age after her husband’s death. Again, in Stern’s potent capping stanza, we read: “This David died in sumer./Esther took the call,/wrapped herself in cashmere/(the coat he slide along her neck)/ and wept.”

What’s Left Out is a summary encapsulation of all sorts of things Esther did not do well, and after the fairly romantic picture drawn up to here, it is a sharp and painful addition again demonstrating Stern’s honesty in rendering her subject.

Again, The Bite, dedicated to Florence, Stern’s mother, is the penultimate poem in the collection, and feels like a key to the creation of this poetic biography of Esther, Florence’s mother. Telling the very straight story of loss, it is a searing hole seeking closure. Telling the grandmother’s tale, working through the romantic images and then the bitter ones, opens a space for remembering the mother who has died too young. A poetic odyssey, from the haloed evocation of an immigrant grandmother through a grave portrait of her challenges and a candid acknowledgement of her limitations, is a kind of preliminary prayer service to this potent final kaddish, this affirmation of life in recollection of the dead. Having recited those requisite preliminary observances with rigor and candor, Stern leaves open the space for this honest and direct calling forth of redemptive tears.

– BADMan

My favorite is Tightly. A wonderful book which renews my faith in poetry.