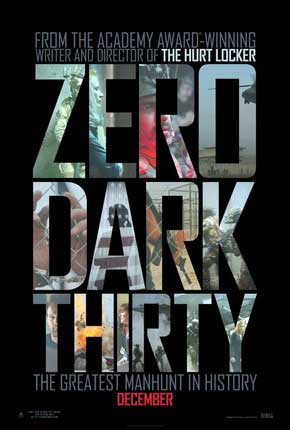

Film (2012)

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow

Screenplay by Mark Boal

Original Music by Alexandre Desplat

Cinematography by Greig Fraser

Film Editing by William Goldenberg, Dylan Tichenor

With Jessica Chastain (Maya), Jason Clarke (Dan), Reda Kateb (Ammar), Kyle Chandler (Joseph Bradley), Jennifer Ehle (Jessica), Harold Perrineau (Jack), Jeremy Strong (Thomas), Mark Strong (George), Fredric Lehne (The Wolf), Mark Duplass (Steve), James Gandolfini (C.I.A. Director), Stephen Dillane (National Security Advisor), John Barrowman (Jeremy)

in “Zero Dark Thirty”

Photo: Jonathan Olley

Courtesy Columbia Pictures

Maya (Jessica Chastain) is a young CIA operative who becomes obsessed with the pursuit of Osama bin Laden. Through sometimes brutal and sometimes crafty means, she manages the intelligence that eventually leads to execution of the mission by American commandos which results in bin Laden’s death.

There is hardly a bad thing one could say about this intelligently written, directed and edited suspense thriller.

Much of the opening of the film involves vivid torture scenes. This is hard to watch, and clearly meant to be so.

There has been much controversy over this film’s depiction of torture, with some commentators arguing that the film implicitly condones it.

I think this intelligently written film makes a far more subtle point. The intent here, without forcing it down the viewer’s throat, suggests that, despite garnering useful information during the Bush administration, brutal methods like waterboarding, banned at the outset of the Obama administration, give way to the more subtle and acute kinds of investigations pursued by agents like Maya, the protagonist of this film.

With delicacy of inflection, the film shows how, despite Obama’s restrictions on torture, Maya uses her wits to pursue bin Laden. The success of that venture is a subtle but potent tribute to those policies and an appreciation of the functions of intelligence over brutality.

in “Zero Dark Thirty”

©2012 Columbia Pictures

This film oddly creates suspense effectively, despite the fact that everyone who sees it knows how it will end.

Director Bigelow’s capacity to portray the known in a way that makes it dramatic is indicative of what great tragedies do. One of the significant traits of classical tragedy is that the audience knows exactly what will happen. The drama, for the audience, is not in finding out about the end, but reliving, through the perceptions of the tragic hero, the calamities undergone.

The same is true of this film, which has no surprise in the end, but which packs a great deal of experiential power nonetheless.

Jessica Chastain’s performance as Maya is stellar. Her entire demeanor in the film conveys determination. This film about a woman, and directed by one, is a tribute to the kind of insistent, but successfully subtle, approach that compares favorably to those pursued beforehand. The entire thrust of the first part of the film is to show that Maya is not a wimp; she witnesses torture sessions willingly, though obviously affected by them. But, later on, when necessary, she pursues things with a nuanced outlook that goes well beyond what her counterparts have pursued.

Jennifer Ehle, a wonderful actress (I saw her brilliant performance in 2007 in Tom Stoppard’s trilogy, The Coast of Utopia, in New York), provides a companionable presence to Maya, reinforcing female wits at difficult outposts in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Ehle (who also delivered a wonderful performance as Elizabeth Bennett in a 1990s BBC version of Pride and Prejudice) can convey striking intelligence without sacrificing empathetic appeal, perfectly suited to the demands here. This echoes the same modes in Chastain’s Maya, whose ferocity of will and incisive analytical powers do not diminish an obvious vulnerability.

The brilliant economy of writing in this film prevents it from dawdling into all the arenas in which it might well have. There are no romances, thankfully; Maya is all business. There are moments when Bigelow creates a shot that makes the audience wonder what else might be going on in Maya’s mind and heart, but, again, the point is subtly raised, not forcefully imposed, and so much more effective for that reason.

In keeping with the high level of this production, the music is so delicately interwoven it creates the requisite mood perfectly without at all becoming a distraction.

Nor are there stupid scenes involving the two presidents. The writer and director wisely focused the energy and attention on Maya and the team with which she works, not elsewhere.

in “Zero Dark Thirty”

©2012 Columbia Pictures

We do get a few scenes with James Gandolfini as a reasonable version of Leon Panetta. Here, contrary to his signature Tony Soprano portrayal, he drops into the action and never dominates it.

One would be somewhat hard put to designate any political slant here. The clear depiction of torture early on and the apparent relief of it later on are indications of policy changes in the Obama administration, as noted before. But the film does not cheer these changes, it merely notes them. And, appropriately, it shows how subtly such changes manifest themselves. At first, through the eyes of these torturing interrogators, the Obama changes seem like an unfortunate restriction; later on, it becomes more of a fact of life. And it is during that latter phase that Maya’s more successful approach to finding bin Laden takes root.

On another level, the film is a delicate reflection on the nature of passion and obsession. Once Osama bin Laden has been killed, we watch the long pan of Maya’s face and wonder what she will now do. It raises questions about how best to direct our communal intelligence in a complex world.

One only hopes that Maya, and ferociously determined people like her, will also turn their efforts to the great problems of humanity – feeding, clothing, housing, educating and caring for all – as well as finding the bad guys when necessary.

– BADMan

Dear BADman, I wouldn’t want to come off as being negative here, because your thoughts are generally so worthwhile and delightfully devoid of cant. And, to put my cards on the table (as you know, personally, because we are acquainted from long since): I am a man of the right. But my antennae twitch a bit (albeit your comments that the film is without political directedness) when you draw inferences about how successful the changes in interrogation policy from the Bush to the Obama administrations were…based on their depiction in a film — which, as an art form, is a massaged version of reality, at best. You may have your opinions on this point, and so may I; chances are, neither one of us are on very good grounds as far as facts go…for the very good reason that the issues at hand are taking place in the secret world. But using a film — even tangentially — as “proof” that policies were (or were not) successful seems unworthy of the level of discourse usually on display around here. All the best, KMcD

I didn’t see any reservations in your review about the use & misuse of torture to elicit confession despite the fact that this was not a decisive factor in the capture of Osama Bin Laden. You write: “The intent here, … brutal methods like waterboarding, …give way to the more subtle and acute kinds of investigations pursued by agents…” Although I have not seen the film your observations are not consistent with other reviews I have read & heard which noted that the film gave a strong impression that torture was necessary in order to elicit the information needed to find Bin Laden. But this was not the case, according to those who were in the know & were closer to the situation so the director of the film should be taken to task for misleading the public about such an important matter. Films, after all, can easily mislead & can embed misunderstandings into the minds of the body politic.

Hugh, re your comment of 2013/02/06 at 8:54 pm:

Thanks for raising this.

There has, indeed, been a lot of press objecting to what is identified as the film’s implicit advocacy of torture. The argument, as you appropriately reconstruct it, derives from the perception that the film depicts the retrieval of a key piece of information during torture that later becomes useful in the discovery of bin Laden.

Not only have journalists raised this objection (notably, among others, Steve Coll in a piece entitled ‘Disturbing’ & ‘Misleading’ in the February 7, 2013 issue of The New York Review of Books and Matt Taibbi’s blog piece from January 16, 2013 on Rolling Stone: ‘Zero Dark Thirty’ Is Osama bin Laden’s Last Victory Over America), but members of Congress, in particular, Senators John McCain and Diane Feinstein, have argued that the film misrepresents the facts, and argue that torture techniques of the sort presented in the film were not instrumental in turning up evidence that was directly related to locating bin Laden.

Other commentators have indicated, differently, that there is considerable murkiness in this history and that those who claim that finding bin Laden had no relationship to evidence turned up in these unsavory ways are not likely to be completely right either. (For accounts of this general approach, see two pieces on Slate: Does Zero Dark Thirty Advocate Torture? by Emily Bazelon (12/11/2012) and Who Are The People in Zero Dark Thirty? by By David Haglund, Aisha Harris, and Forrest Wickman (1/14/2013). Bazelon’s piece, in particular, gives refers to the interrogation of Hassan Ghul, who is thought to be the inspiration for the character named Amar in Zero Dark Thirty, who, under torture, yields the information about bin Laden’s courier which eventually leads to bin Laden. According to Bazelon’s sources, Ghul was not waterboarded under interrogation, but may well have been subjected to other harsh techniques. Bazelon’s account of Ghul, as well, brings into question Senator McCain’s objection to Zero Dark Thirty that Amar was an analogue for Khalid Sheik Mohammed, who, as McCain contended, provided no relevant information that led to finding bin Laden.)

I do think that critics of the film have raised important concerns about the film’s hovering on the boundary of fact and fiction, and have brought into focus the potential for greater confusion by the film-going public about the history that inspired the film. In defense of the film, however, I would argue the following.

It would have been odd in a totally different way if the filmmakers had chosen not to include torture an element of the story; my sense, from seeing the film, is that its creators wanted to be honest about its role without celebrating it.

As some have argued, the filmmakers might, indeed, have presented their story equally effectively by depicting a nonexistent, or far less direct, relationship between evidence turned up in torture and the successful tracking of bin Laden; that would have allowed the rest of the story to unfold, more or less unchanged, while keeping its main narrative thrust – that determination and ingenuity over the long haul on the part of a single agent or a small group of agents, was the real vehicle for finding bin Laden.

Though this seems like it might have been a plausible alternative narrative strategy, I do understand why the filmmakers chose not to use it. In acknowledging that torture was a part of the history, though a grim one, they depict its possibly significant role, but do so in a way that, in my experience of the film, does not glorify it. Had I felt that they did, I would have objected strongly to the film and to its implications. I found, alternatively, that the film depicts torture as not only inhumane, but as of limited use in deriving consistently reliable information, despite acknowledging that a piece of that evidence eventually connects to the tracking of bin Laden. The thrust of the narrative, however, shows that that piece of information is only identified, much later, as useful because of the focus of a determined agent.

As you note, concern about how the public might put these depictions together, and possibly use them to justify torture, is a relevant concern. However, the film’s tone, as I perceive it, does not encourage a simple response of this sort. Though the film is highly suspenseful, its tone, even in the climactic moments, is subdued rather than glorious, encouraging more complicated reflection rather than unmitigated celebration.

Nonetheless, there are plenty of responsible and thought-provoking critics like Taibbi and Coll, who, having seen the film and who appreciate its high level of craft, still object to its potential political and moral implications.

You are indeed right – it would have been better for me to acknowledge those diverse and important viewpoints in the case of this very well done, but controversial, film.

– BADMan

Kevin, re your comment of 2013/01/29 at 10:34pm:

Thanks for raising this important point about the need to carefully separate artistic criticism from personal political stances, and, as well, for suggesting a subtle inconsistency in my account.

If I am not mistaken, the following passages in the above review contain this sort of confusion about evaluating a work of art and expressing a personal political viewpoint:

The intent here, without forcing it down the viewer’s throat, suggests that, despite garnering useful information during the Bush administration, brutal methods like waterboarding, banned at the outset of the Obama administration, give way to the more subtle and acute kinds of investigations pursued by agents like Maya, the protagonist of this film.

One would be somewhat hard put to designate any political slant here. The clear depiction of torture early on and the apparent relief of it later on are indications of policy changes in the Obama administration, as noted before. But the film does not cheer these changes, it merely notes them. And, appropriately, it shows how subtly such changes manifest themselves. At first, through the eyes of these torturing interrogators, the Obama changes seem like an unfortunate restriction; later on, it becomes more of a fact of life. And it is during that latter phase that Maya’s more successful approach to finding bin Laden takes root.

The expressed approval of changes in policy from the Bush administration to the Obama administration does not make clear whether that is a personal opinion or an account of film’s perspective. Indeed, I might have been clearer. Though I do personally applaud that change of policy, I also regard the film as applauding it, but in an implicit and subtle way.

That, indeed, leads to your second point, about the inconsistency.

By my saying that one would be somewhat hard put to designate any political slant here, and then contending that the film, albeit in an implicit and subtle way, applauds the change in policy from Bush to the Obama administrations, is indeed an inconsistency. I might have better said that one would be somewhat hard put to designate an overt political slant here, which would have maintained that, in broad strokes, the film does not take political stances, while acknowledging the subtlety of that slant that I do think it conveys.

– BADMan