Paintings by Monique Johannet

Carroll and Sons

420 Harrison Avenue, Boston

May 23 – June 30, 2012

Oil on canvas, Two canvases

30 x 30″ top, 15 x 30″ bottom

Courtesy of the artist and Carroll and Sons

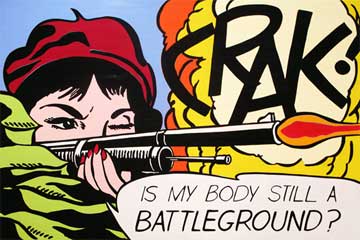

Roy Lichtenstein is the pop artist who made a successful career from paintings that, in large format canvases, emblazon single cartoon panels, often with kitschy and ironic balloon dialogues. Newsprint dots permeate these scenic representations, always reminding us that these paintings are derivations from another medium.

Monique Johannet has taken, in turn, some of Lichtenstein’s images and refashioned them according to her own sense of irony and vision. First of all, she removes the newsprint dots. Perhaps, in doing so, she reminds us that she derives her work from Lichtenstein’s and that it is consequently a representation of a representation.

The dots, instead, are plucked off the individual canvases and pepper the walls of this show. Each dot is a small canvas unto itself, a flat painted asteroid. Collectively, they hover in a sky against which the cartoonlike constellations are displayed.

Oil on canvas, 24 x 18″

Courtesy of the artist and Carroll and Sons

The overall theme is feminist and ironic. By and large adapting the images from Lichtenstein’s originals, Johannet changes the text from them to suit her own purposes. Consequently, what, in the sixties, in Lichtenstein’s hands, seemed like a funny re-representation of a comic panel, fifty years later, in the hands of a woman painter, takes on a different tone.

And, thereby, a theme and sense of mission in Johannet’s series comes through clearly. The original framings of pop art culture were a kind of ironic reflection of the facile and commercial productions that inspired them. By representing them on canvas, artists like Lichtenstein – and certainly Warhol – were able to crack a smile at those productions and get us to look a little bit askance at them. Now, stretching across a gender and half a century, Johannet cracks a secondary smile at that original smile, suggesting that there is now much more to laugh about, in several dimensions.

The original ironies take on a different dimension when the artist as well as the protagonist of the panels is a woman. And the fifty years of political and sexual evolution echo throughout, mixing the plaintive tones of longing with a more fully realized sense of autonomy. But Johannet, a female artist, speaks through the panels in a way that Lichtenstein could not. In this sense, the removal of the dots reflects another shift, indicating that representational distance here is shortened through the voice of a woman artist.

So, the title of the show makes perfect sense. “Is it something I said?” signifies a question that the artist now asks through the characters in the panels in a way that the original on which they are based never could.

Oil on canvas, 48 x 72″

Courtesy of the artist and Carroll and Sons

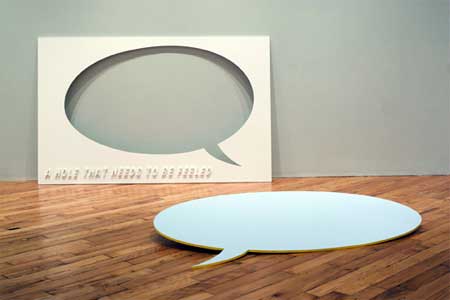

This is indeed a show for students of semiology (the study of signs) who love to think about what is representing what, and what the attempt to represent, in itself, is all about.

Lichtenstein represented comics, which themselves are already representations of human dramas. Now, Johannet represents Lichtenstein, another step away, threatening, with the recursive loop of inner referencing, to bring down our computational networks. In doing so, she asks how far we can go in establishing representations of representations before our primal intuitions send us back to the source, to the original, to the places where the feelings echoing through the repeated echoes of those episodic comic emblems might actually arise.

Enamel on wood

Two parts, 48 x 76″ and 45 x 62″

Courtesy of the artist and Carroll and Sons

There is also a painterly gesture that the artist subtly raises, in lowered voice, as though offstage.

Unlike the edges of Lichtenstein’s paintings which are as hard-edged and clear as the faces, the edges of Johannet’s paintings bleed. The front of her paintings are all pop clarity, but the sides of the canvases ooze with the freedom and unknown boundaries of abstract expressionism, as though the artist knows that the wild dancer, at any point, is ready to spring out from the wings of this carefully demarcated proscenium and take to exuberant flight.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply