Play (2008)

by Anna Ziegler

The Nora Theatre Company

Central Square Theater

Cambridge, MA

February 9 – March 4, 2012

Directed by Daniel Gidron

With Becky Webber (Rosalind Franklin), Owen Doyle (Maurice Wilkins), Jason Powers (James Watson), James Bocock (Francis Crick), Nick Sulfaro (Ray Gosling), Jeremy Browne (Don Caspar)

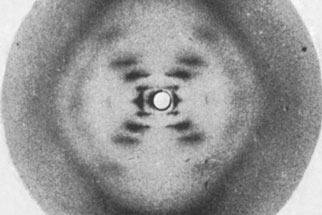

In the early 1950s, Rosalind Franklin (Becky Webber), a young, impassioned xray crystallographer, came to the University of London. She began work on the structure of DNA, collaborating with senior researcher Maurice Wilkins (Owen Doyle) and graduate student Raymond Gosling (Nick Sulfaro). Her scans produced results that were directly related to the discovery of the helical structure of DNA. James Watson (Jason Powers) and Francis Crick (James Bocock), working in a different laboratory, specifically made use of the eponymous Photograph 51 taken by Franklin to derive their model of the double helix.

Crick, Watson and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962 for their contributions to this discovery. Franklin passed away in 1958 at the age of 37 from ovarian cancer, presumed to have been related to her exposure to the radiation used in her research. Since the Nobel is not given posthumously, she did not receive the much deserved award.

Photo: A.R. Sinclair Photography

Tracing the history of Franklin’s contributions to this discovery, the play not only exhibits her determination but explores the complexities arising from being a forcefully visionary woman in the company of men.

Beginning with Franklin’s arrival at the lab, Photograph 51 follows, in particular, her complex relationship with Wilkins. Suggesting unvocalized personal attractions, particularly from his side, it exhibits the turbulence created by her professional zeal and the resulting abrasions in their relationship.

As well, it includes depictions of her peacefully collaborative partnership with Ray Gosling, the graduate student who assisted her, and with Don Caspar (Jeremy Browne), a fellow researcher who seemed as well to pose the possibility of a more intimate connection.

Becky Webber as Rosalind Franklin

Photo: A.R. Sinclair Photography

In the surrounding landscape hover Watson and Crick, rivals in the search for the structure of DNA. Largely, the drama is fueled by that race and the contest of wits and wills between the Watson-Crick team and that of Franklin, Gosling and Wilkins.

Though interestingly focused on this important piece of scientific history, the play hovers around the scientific issues, spending more of its time alluding to rather than delineating them.

More extensively devoted to the personal interactions between the characters, it speculates whether Wilkins loved Franklin, despite her abrasiveness.

Was Franklin simply a hard-working woman researcher who had to defend herself against the ignominy foisted upon her in the male-dominated scientific world, or was she a social misfit who was unable to work collaboratively? The play raises these alternatives, without taking a definitive stance.

The play is most effective when clearly exhibiting the inequities that affected Franklin. Would Wilkins honor her expectation to do independent research or would he make her intellectually subservient to himself? That is not so clear at the outset. When the subject of lunch comes up, Wilkins mentions he is going off to an all-male faculty club, excluding Franklin. These dramatic points are subtly presented and come through clearly and significantly.

Less successful are the explorations of possible affection between Wilkins and Franklin. The merest hint of that issue might have been effective, but Ziegler makes it into more than that.

Becky Webber is a dutifully engaging Franklin. Her performance suggests an ambiguity in Franklin’s abrasiveness (alluded to above) that seems either a clear response to male chauvinism or an indication of a character disorder. I’m not sure that ambiguity works, but this production seems to intend it.

Owen Doyle, as Wilkins, is effectively stilted and formal, effectively conveying the balance of hidden affection and restraint.

Jeremy Browne (Don Caspar) and James Bocock (Francis Crick) put in appropriate and measured performances.

I saw Nick Sulfaro not long ago as a stupendous and memorable Angel in the New Repertory Theatre’s production of Rent. In this much more sedate role, he is capable and affecting, demonstrating another pole of a considerable dramatic range. I will be on the lookout for what he does next.

Jason Powers gives a very kinetic interpretation of James Watson, making one wonder whether he was an overly ambitious young scientist or a speed freak. Presumably Watson exhibited some extreme qualities, but the depiction here seems too hyper even for him.

This piece of intellectual history and the associated feminist issues raised are most important, and the play and the production are to be credited with bringing those to light.

-BADMan

Leave a Reply