Book, music, and lyrics by Jonathan Larson

Directed by Benjamin Evett

Musical direction by Todd C. Gordon

Choreography by Kelli Edwards

New Repertory Theatre

Watertown, MA

September 4, 2011 – October 2, 2011

With John Ambrosino (Mark), Julia Broder (Woman #2), Danny Bryck (Benny), Aimee Doherty (Maureen), Eve Kagan (Mimi), Robin Long (Joanne), Joe Longthorne (Man #2), Grant MacDermott (Man #1), Andrew Oberstein (Man #4), Adrienne Paquin (Woman #3), Maurice E. Parent (Tom Collins), Matthew A. Romero (Man #3), Cheryl D. Si1ngleton (Woman #1), Robert St. Laurence (Roger), Nick Sulfaro (Angel)

It is the 1980s in Manhattan’s East Village. Mark is a filmmaker who shares a tenement with a community of varied souls; many of them have AIDS. His housemate, Roger, a guitarist, and a former heroin addict, is one of those afflicted; he struggles to write one good, last song before he dies. Angel, a charming transvestite (male to female), also has AIDS, as does Tom Collins with whom she falls in love. Roger, in a more complicated way, falls in with Mimi, a beautiful exotic dancer (who has AIDS and is using heroin). The tenement in which they live comes under rent payment demands by its new owner, a former housemate named Danny who has gone to the dark side and become a businessman. In a tragicomic turn, Mark’s girlfriend, Maureen, who has just left him for a woman named Joanne, leads a dramatic protest. Over the course of a year a couple of the characters die, bringing the challenges of survival and creation into relief.

Created by Jonathan Larson in the 1990s, Rent was based closely on the plot of Puccini’s opera, La Bohème. Part of the musical elements in Rent allude directly to the opera, most notably in Roger’s guitar solos which replicate Musette’s Waltz, a famous second act aria in the opera. (Musette is the model for Maureen. Rent’s tragic heroine is named Mimi, exactly as in the opera; the model for Roger is Bohème’s Rodrigo.)

The other wildly successful, relatively contemporary, musical based on a Puccini opera is Miss Saigon by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil; it takes its framework from Madame Butterfly. Set in Vietman during the war in the 1960s and afterwards in the United States, Miss Saigon’s plot also, as does Rent’s, replicates its Puccini model’s narrative very closely.

Miss Saigon, and the earlier, also highly popular, work by Schönberg and Boublil, Les Miserables, have a kind of lyrical and musical tautness which is quite different from the improvisational roughness Rent exhibits. Both styles are compelling, but Schönberg-Boublil gravitate towards a tragic-majestic style while Larson exhibits a grittier mode, well-suited, indeed, to its bohemian subject-matter.

Rent’s roughness (both narratively and musically) makes it at once particularly appealing and artistically vulnerable. Refreshingly untutored, it is unlike much of the carefully honed material that makes it to the Broadway musical stage. But that unusual quality also makes it sometimes not quite as tight as it might be.

Its contour reminds me – to make a leap across decades and art forms – of Bob Dylan’s album Planet Waves, which caused a sensation when it came out (in the early 1970s) because of its own comparative roughness. When a lot of music was getting more finely and technically produced, Dylan chose to issue an album that repudiated that trend. It was gruff, insistent, revelatory and courageous. It deserved to have its best-known track be called Forever Young.

A few years later, of course, punk rock, which made a religion of repudiating overly refined record producing, came into full force. An army of punk bands filled the East Village and hovered around the famous club CBGB. That religion of gruffness, that repudiation of sleekness made more visceral and vulnerable by the AIDS crisis which followed close on, sets the tonal background for Rent.

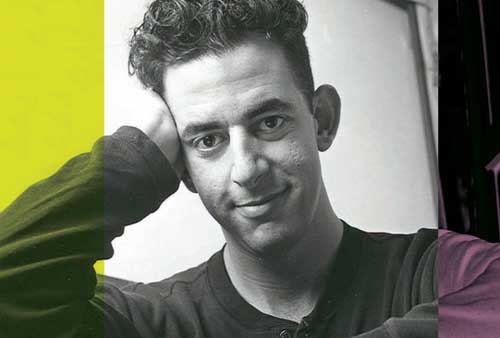

While noting an occasionally vulnerable musical and narrative underbelly, let us be fair to the creative context of this very appealing work. Its framing as well as its framed story is tragic. Its highly talented author, Jonathan Larson, died suddenly of an aortic hemorrhage (technically an aortic dissection thought to have been caused by Marfan’s Syndrome – Wikipedia) just short of his 36th birthday, less than a month before Rent’s world premiere. Rent, with all of its roughness, thus carries additional dramatic-memorial weight (like the works of van Gogh or Jackson Pollock) because of a its creator’s premature death.

The director, Benjamin Evett, is the founder and former artistic director of The Actors’ Shakespeare Project, a very fine, relatively new, theatre on the Boston scene. Before that, Evett had been a longstanding member of the resident company at the American Repertory Theatre. He is a gifted actor and a bold and energetic director. Recently, he exquisitely performed the role of Dorian, the violist, in Opus, Michael Hollinger’s play, given a beautiful production at the New Repertory Theatre last year.

The current production of Rent has a good deal of wonderful, lively energy and some great moments. It is a more musically complex work than its overt gruffness would lead one to believe, and there are some places in which the subtlety of intonation requires a bit more honing than was evident in this performance. I saw the show at the beginning of its run; I would expect those kinks to get worked out over time.

It is quite a different thing to present a musical with a limited run of this sort from the finely tuned Broadway productions that extend for week after week at home or on the road. Rent, of course, was on Broadway for a long time and one might be inclined to measure a production like this against one like that; I think that would be a mistake. The current production has a smaller scale and an even more raw quality than a Broadway production would have. And some of the interesting and idiosyncratic portrayals here have the chance to cut more loosely and improvisationally into the fabric of this now established work of American musical theatre.

There are many good performances among all the members of this young cast and one that struck me as truly outstanding.

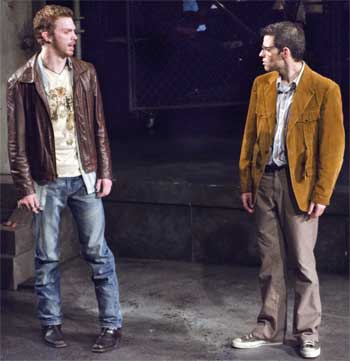

Photo by Andrew Brilliant/ Brilliant Pictures.

John Ambrosino brought a solid quality to the central role of Mark. Aimee Doherty was funny and energetic as Maureen. And Eve Kagan had a kind of wild, animal allure in the role of Mimi. Maurice Parent as Tom Collins and Robert St. Laurence as Roger were both dramatically and vocally capable. Julia Broder, in a very limited cameo role as Mrs. Cohen, Mark’s mother, managed to be very funny indeed.

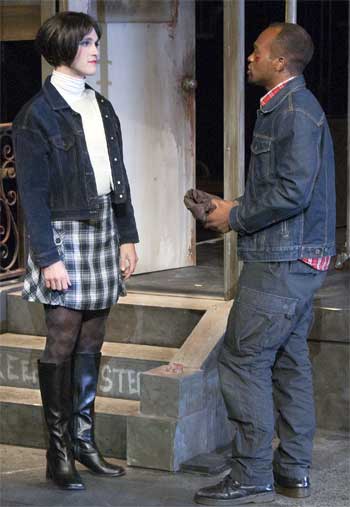

Photo by Andrew Brilliant/ Brilliant Pictures.

The real standout, however, was Nick Sulfaro as Angel. He conveyed the character with heart, warmth and gusto. There was pathos in the role and a great deal of energy. It is the most heroic role in Rent, and he lived up to it superbly.

Photo by Andrew Brilliant/ Brilliant Pictures.

The show is by now a classic, and one cannot argue too much with its success. However, it is clearly the work of a young artist who did not sculpt or pare away quite enough. It goes on a bit long, has musical numbers that could be shortened or cut, and there are elements of the story that could be further shaped. But, like the works of the late, great writer David Foster Wallace, who wrote at great length and whose life was far too short, we now must accept Rent with its many virtues – in its somewhat unsculpted form – with gratitude for the energy and vision with which it was produced.

Apart from some intermittent vocal intonation issues, the music was well done. The staging and choreography, involving a large cast, did convey much of the time the raw energy and desperation of the era. One number, however, involved the entire cast standing in place waving back and forth in an unspecified way accompanied by a vocal solo that did not quite rise to its appropriate note targets, all combining somewhat painfully. There were sound balance issues generally; frequently the vocalists were drowned out by the instrumentalists. Given the expected working out of those issues, this production of Rent is likely to further distill and artfully exhibit the raw energy of this great show over the course of its run.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply