Play (1961)

by Tennessee Williams

Directed by Michaal Wilson

American Repertory Theater

Loeb Theatre, Harvard University,

Harvard Square, Cambridge, MA

February 18 – March 18, 2017

Scenic Design: Derek McLane; Lighting Design: David Lander

With Bill Heck (Reverend T. Lawrence Shannon), Amanda Plummer (Hannah Jelkes), Dana Delany (Maxine Faulk), James Earl Jones (Nonno), Elizabeth Ashley (Judith Fellowes), Kiko Macan (Pancho), Mike Turner (Pedro), Matt Morrison (Hank), Richmond Hoxie (Herr Fahrenkopf), Stacia Fernandez (Frau Fahrenkopf), Hanna Sharafian (Hilde), Ben Winter (Wolfgang), Susannah Perkins (Charlotte Goodall), Remo Airaldi (Jake Latta)

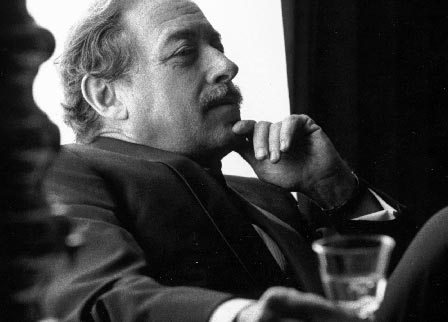

James Earl Jones as Nonno

in “The Night Of The Iguana”

Photo: Gretjen Helene Photography

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

Reverend T. Lawrnece Shannon (Bill Heck) has had his problems keeping with the religious program and, as a result of dallying one too many times, has been forced into driving buses of tourists to Mexico. At this juncture, he lands at the resort run by the recently widowed but lusty Maxine Faulk (Dana Delany), who seems to have a thing for Shannon despite his issues. In addition to a gaggle of tourists that Shannon has brought along, a New England spinster, Hannah Jelkes (Amanda Plummer), and her ninety-seven year old poet grandfather, Nonno (James Earl Jones) show up. In the midst of complications produced by Shannon’s antics, Hannah and Shannon strike up an unexpectedly intense connection.

Though this play has some degree of plot to it, the greatest element of its drama lies in the development of the relationship between Shannon and Hannah. Wonderfully and subtly developed in the first half of the play, this relationship grows almost organically out of their strangely opposing inclinations. Shannon, though putatively a Reverend, is depicted as much more of a roué, a desperate and irresponsible man running on empty. Hannah, middle-aged and schoolmarmish, seems completely reserved, contained and as physically shy as Shannon is bold, yet she has a kind of existential gutsiness that challenges Shannon to his core.

On the title page of a typescript draft of the play, copied and displayed in the lobby, one can see Williams invocation of a quote by Emily Dickinson as the play’s epigraph. Plummer’s exquisite rendering of Hannah seems to derive much of its energy from that Dickinsonian example – one who is physically reserved, almost pathologically isolated, but metaphysically and psychologically as bold as they come. It’s a lovely portrayal by Wiliams and a beautifully interpreted version of it by Plummer and director Michael Wilson. It invokes so clearly that sense of moral courage and the capacity of those who possess it to offer significant and inspired connection with those who are socially and physically bolder but more psychologically impaired.

In many ways, the first part of the play is impeccable, a carefully explored and articulated drama about the evolution of this unexpected relationship and the waves that it causes especially for Maxine. The second part of the play, while preserving the essential tone of the whole, works a bit too hard to push its symbolic theme and to provide dramatic closure. The focal attention on the potential release of the iguana, the abbreviated treatment of Hannah’s extreme physical reserve, Nonno’s timely transition, and the manner of working out things for Hannah, Shannon and Maxine all seem a bit too convenient dramatically.

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

In a wonderful letter to readers of the original playscript also displayed in the lobby, Williams defends the subtlety of the psychological drama in the play. He offers an assured response to what seems to have been their criticism that there was not enough ordinary dramatic suspense. Yet, given some of the dramatic conveniences of the second part of the play, one wonders how much he might have been influenced.

In any event, this production succeeds extremely well in preserving the core of emotional drama throughout.

Bill Heck’s interpretation of Shannon is powerful and persuasive in many ways, but it seems as though the Reverend part is all but missing. This production’s interpretation suggests a character more like Stanley Kowalski who accidentally winds up in divinity school and turns into the class rowdy. To be sure, Heck’s portrayal is lusty and vivid but just hints at that more complex something which enables him to be drawn to Hannah’s sensitively resolute temperament.

As Nonno, the aged grandfather poet of Hannah, James Earl Jones has a fairly modest supporting role, but fills it with such resounding feeling that it fills a much greater space than it seems to occupy. Jones’s performance is grand and resonant, and when he recites his final poem for Hannah to transcribe it has an entirely hypnotic quality that holds the theater in pure aesthetic suspense.

Elizabeth Ashley (Judith Fellowes) also has a small role as the leader of the tour group, but she fills it with gusto and great humor. And, as the actress who starred in the Broadway revival of Williams’ Cat On a Hot Tin Roof in 1974, she carries with her the considerable force of tradition.

in “The Night Of The Iguana”

Photo: Gretjen Helene Photography

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

Dana Delany (Maxine) gives a nicely down-to-earth rendition of the lusty resort owner and her subtle conveyance of the character’s combined jealousy and acceptance are noteworthy.

Written in a different era when stage plays could more normally support a stable of actors, Iguana has fourteen in all, and though the rest of the supporting cast do a reasonable job, most of these roles are inconsequential.

Derek McLane’s set design for this production is beautifully conceived, David Lander’s lighting design that goes along with it is magical, and real rain falls at the end of the first half. Such distinctive stagecraft ably informs and assists the superb acting and direction, helping to create a magical and persuasive result.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply