Film (2013)

Directed by Margarethe von Trotta

Screenplay by Margarethe von Trotta, Pam Katz

With Barbara Sukowa (Hannah Arendt), Axel Milberg (Heinrich Blücher), Janet McTeer (Mary McCarthy), Julia Jentsch (Lotte Köhler), Ulrich Noethen (Hans Jonas), Michael Degen (Kurt Blumenfeld), Nicholas Woodeson (William Shawn), Victoria Trauttmansdorff (Charlotte Beradt), Klaus Pohl (Martin Heidegger)

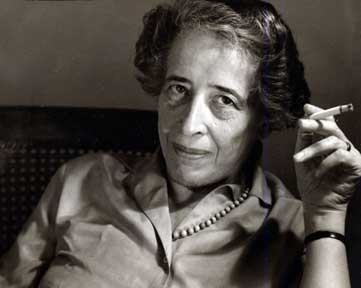

in “Hannah Arendt”

Photo by Véronique Kolber – © 2013 – Zeitgeist Films

Hannah Arendt (Barbara Sukowa), a Jew born and raised in Germany, and inspired by, and romantically involved with, the great German existentialist philosopher, Martin Heidegger (Klaus Pohl), escaped to the United States after imprisonment in a detention camp in France during the Nazi era. She married German-born poet and philosopher Heinrich Blücher and embarked on a successful career as a philosophy professor at The New School for Social Research in New York, gaining high regard, as well, as the author of several works in social philosophy, including The Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition.

In the early 1960s, when the high ranking Nazi Adolf Eichmann was captured by the Israeli secret service in Argentina and deported to Israel to stand trial for his crimes during the war, Arendt got a commission from The New Yorker magazine to attend and to report on the trial. The result was a series of articles that later emerged as Eichmann in Jerusalem. In that controversial book, Arendt coined the term “the banality of evil,” which signified the dominant impression she had of Eichmann as an unthinking cog in the Nazi machine.

Though this film is simply named “Hannah Arendt,” and suggests a far broader treatment, the focus of it is the controversy over Arendt’s writings about Eichmann. Her relations with a few central characters become focal. These include her husband, Heinrich Blücher, her good friend, the American novelist Mary McCarthy, her colleague in philosophy at The New School, Hans Jonas, and her old friend from Germany who had moved to Israel, Kurt Blumenfeld. As well, the editor of The New Yorker, William Shawn (Nicholas Woodeson), figures notably in the action. A series of flashbacks with Heidegger at the early stages of their relationship surface at various points.

Though about intellectuals, this is not an intellectual film. One would think that in depicting scenes in which Arendt’s various colleagues – notably Jonas and Blumenfeld – take severe umbrage at her position on Eichmann, there would be more argumentation. There is, however, very little. One sees scenes in which Jonas and Blumenfeld turn away from Arendt in anguish, but, apart from saying something very general in exasperation about how she betrayed the Jews, there was, from both of these intellectuals in this film, no further articulation.

Instead there is a lot of dwelling on Arendt looking pensive and determined, and smoking a great deal. And there is, as well, an abundance of time spent showing just how happy and in love with Blücher she is, which seems just a bit too much. (In fact, Arendt’s relationship with Blücher was somewhat more complicated than the film suggests.)

Another woefully shortchanged depiction involves her relationship with Heidegger.

The film shows her as a young woman deeply inspired by Heidegger’s teaching and example. She asks him to “teach her how to think” but, in relatively short order, we see him entering her apartment for something more than a lesson in thinking. Heidegger was married, had a couple of children, and was considerably older than Arendt, though we do not get much at all about Heidegger in this abbreviated depiction.

The filmmaker suggests that Arendt’s inspiration to think à la Heidegger leads her, later on, to analyze Eichmann as she does. That Heideggerian thinking is not superficial conceptualizing or argumentation, but characterized as a deeper and more penetrating look into things, gives intended weight to Arendt’s reflections.

This is a reasonable point and relevant clarification of Heidegger’s style of influence on Arendt’s style of thinking, but the rest of the film’s allusion to Heidegger is not only incomplete but misleading.

Before the 1980s, when serious study of Heidegger’s role as a Nazi began to take place, it was possible to pass off Heidegger’s public affiliation with the Nazi party as the short-lived and politically unsophisticated gesture of an ivory tower intellectual. In fact, as extensive research revealed in the 1980s and beyond, was not only a card-carrying Nazi for the full twelve years of their domination in Germany, but he was far more politically sophisticated and involved than had been previously thought.

This film, in its abbreviated, but misguided, allusion to Heidegger, puts forward the abandoned view of Heidegger as the bemused intellectual who stumbled inadvertently into politics only to withdraw shortly afterwards. Either the filmmakers were seriously limited in their research on Heidegger, or they simply found it more convenient to depict him this way in order to better focus upon the story about Arendt and Eichmann.

In many ways, Arendt’s continuing friendship with Heidegger after the war is a more compelling and ambiguous moral tale than is her position on Eichmann.

Heidegger was, in no sense, banal, but he maintained affiliation with Nazi party throughout the war and, afterwards, never adequately repudiated, or even explained, his position. How indeed would Arendt assess Heidegger’s affiliation with the party that could so efficiently exterminate millions? His connection could not be simply explained away by referring to the banality of evil. But somehow Arendt managed, through her own combination of enduring affection for him and deep appreciation for what he taught her, to act as though she had forgiven his Nazi affiliation as mistaken judgment. How could Arendt, a devoted student of the sort of penetrating thinking Heidegger presumably practiced, regard the dedication Nazi of this great thinker as a mistake? This curious inconsistency in Arendt’s critical outlook represents a more significant gap in judgment than is her inadequately described, but not entirely wrongheaded, view of Eichmann.

Nonetheless, there are many who continue to feel enraged at Arendt for her position on Eichmann.

Though Arendt’s characterization of Eichmann’s banality seems, to some, like a uniquely appalling perspective, it becomes less offensive if one sees choice of terminology, rather than the underlying idea, as problematic. What gives the term offense is the connotation of its ordinariness. Those who rage at Arendt’s analysis refuse to see anything ordinary at all in the Nazi temperament, whether in the guise of a bureaucratic functionary like Eichmann or not.

In moderately altered terms, Arendt might have identified Eichmann as a sociopath – as one who, without apparent remorse, simply was able to carry out horrific acts. But, banality suggests a kind of bland commonality, whereas sociopathy suggests uniquely offensive insensitivity. Arendt’s attempt, in some part, was to say that sociopathy became common under Nazism, not that its cruel insensitivities were, in any other sense, ordinary.

The use of the term banality suggested the ease with which this sociopathy did, and might otherwise, occur on a broad scale; but its other connotations were an unfortunate complication. Were Arendt to have listened to the calloused recounting of a hit-man, her account might, indeed, have been similar. Did she expect every Nazi to be vengefully impassioned like Hitler? But, to ascribe banality to failing to find premeditated rage in such characters reflects a less than judicious choice of words despite the cogency of the observation that there is sometimes nothing so striking about these willing executioners other as their dulled and blunted sensibilities.

How great it would have been if this film dealt with some of these subtleties through discourse among the intellectuals portrayed.

The picture of Arendt figured by the film as a courageously independent thinker who would not step down from an unpopular stance on Eichmann squares inconsistently with romanticized and uncritical view she takes of Heidegger. This film, however, does not deal with that, nor does it deal critically with any of the arguments taken up so viscerally against her.

It is an interesting, but impressionistic and episodic, portrait of this notable twentieth century philosopher that shows something of the intellectual circles within which she traveled while not really giving the viewer a sense of the vital intellectual discourse that made those circles what they were.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply