Film (2012)

Directed by Pablo Larraín

Screenplay by Pedro Peirano

Inspired by the play The Plebiscite by Antonio Skármeta

Cinematography: Sergio Armstrong

Film Editing: Andrea Chignoli

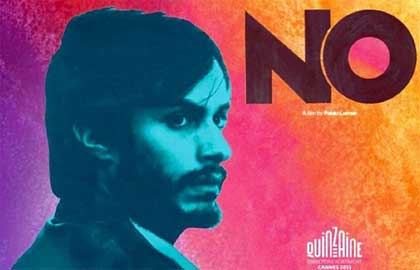

With Gael García Bernal (René Saavedra), Alfredo Castro (Lucho Guzmán), Luis Gnecco (José Tomás Urrutia), Néstor Cantillana (Fernando), Antonia Zegers (Verónica Carvajal), Marcial Tagle (Alberto Arancibia), Pascal Montero (Simón Saavedra), Jaime Vadell (Minister Fernández)

in “No”

Image: Sony Pictures Classics

René Saavedra (Gael García Bernal) is the protagonist of this film – an advertising wizard who puts his talents to work trying to figure out the best approach to defeat Pinochet. He realizes that a head-on attack on the regime is the wrong approach, and that people would need to be eased into the idea of change. Using humor, music and a light touch, he creates a campaign that nudges people in the right direction.

This very good film has something of a cinéma vérité quality about it. Not sleekly produced, it has a rough and ready quality that suits the material very well. The political scene it conjures is complex. There are mixed allegiances everywhere, and comrades at work can easily be political opponents outside.

Despite the invitation to have a referendum, the Pinochet regime exhibits the brutality and manipulation that it always had, adding a tense dimension to the film. Though not intentionally a thriller, it very naturally becomes one because of the threat of instant political repression.

This film demonstrates a certain similarity to Zero Dark Thirty, the recent controversial take on the tracking of Osama bin Laden. Both films focus on the hidden, yet profound, impact of a single motivated, and motivating, character. In Zero Dark Thirty, that character is a female agent in the CIA whose dedication and intelligence are the driving force behind the eventually successful mission. In this film, René Saavedra, the same kind of obsessive genius, quietly, and with enormous focus and intelligence, changes the course of history.

The film does a wonderful job of showing this kind of talent at work.

Its application has its meretricious aspects; after all, Saavedra is an advertising guy, a more contemporary, Latino relative of the 1960s characters portrayed in the television drama Mad Men (2007 -).

There is also, however, an interesting and relevant curiosity about political change here. The film suggests that one need to come at it obliquely, not full of portentous and overblown rhetoric, but cautiously and somewhat self-effacingly.

Antonia Zegers as Verónica Carvajal

in “No”

Image: Sony Pictures Classics

The last scene of the film, after the public referendum has occurred, shows Saavedra in an advertising meeting related to the production of a new TV show.

The proposed setting, subsequently depicted, includes a group of scantily clad women on the top of a high rise building, engaged in conversation with a TV personality who hovers nearby in a helicopter. This is a direct quote of the opening scene of Fellini’s film epic La Dolce Vita (1960), in which essentially the same scene occurs over an apartment house roof in Rome.

La Dolce Vita is a film about despair in the face of quashed idealism in which Marcello Mastroianni plays a journalist caught between high aspiration and meretricious indulgence. The main character in No, like the main character in La Dolce Vita, is a part of the frequently tawdry publicity world. However, in No, that character finds a social mission and sense of purpose that the protagonist of La Dolce Vita does not. Both films portray the whimsical embellishments of desperate circumstances. In La Dolce Vita, idealism lurks around the corner, just out of reach, lending it an existentialist flavor. In No, idealism and tawdriness are woven into the same fabric; the palpably significant outcome oddly emerges from the meretricious world within which it gestates.

There has been some controversy about the historical basis of this film. Watching it, one assumes that the advertising campaign invented and supervised by Saavedra was the only significant factor in the plebiscite.

Apparently, according to Genaro Arriagada, the leader of the actual “No” campaign in 1988, the film is a grave exaggeration of the role of advertising, failing to note the role of the grassroots public education movement.

Director Pablo Larrain, in response, argued for the liberalities afforded by art, justifying the film’s bent by declaring it a drama, not a documentary.

Interestingly, last year, the performance raconteur Mike Daisey was taken to task by the staff of National Public Radio’s This American Life for a breach of facts in his piece that aired on that show about the conditions at the Foxconn plant in China where much of Apple’s products are fabricated. Daisey essentially made the same argument, that he was doing dramatic monologue rather than reportage, and, given that context, factuality could be stretched accordingly. (FYI: Daisey very recently performed an unrelated piece, American Utopias at Arts Emerson.)

Larrain’s argument, and Daisey’s, are less than satisfying, especially when their works hover so precariously near facts without announcing, or otherwise indicating, their departure from them.

A similar conversation has arisen around other semi-factual, politically motivated, dramatic films of the past year, with varying degrees of public rebuke.

Argo, a story of an artfully engineered escape from Iran at the time of the hostage crisis, won the Academy Award this year for best picture; based in fact, but embellished and dramatized in various ways, it did not get taken too much to task for its dramatic departures.

To the contrary, Zero Dark Thirty, based on the story of the tracking down of Osama bin Laden, and also, to a considerable degree, on fact, was, despite its excellence of writing and direction, spurned entirely at the Oscars; it was taken severely to task for what was presumed, by many, despite quite convincing arguments for questioning this conclusion (see Emily Bazelon, Slate, 12/11/2012, Does Zero Dark Thirty Advocate Torture?), to be an adjustment of fact that led to a perception of the utility of torture.

One presumably might argue that Shakespeare, in his history plays, bent the facts, as well, for the sake of drama, and try to trump any further discussion that way. But that would remove the possibility of a more nuanced approach that would seem desirable when looking at these more contemporary political accounts.

The problem is that the representation of an historic event, particularly a nearly contemporary one, in a dramatic piece can easily lead on an audience to believe it as fact. Here, had I not read about the challenge to Larrain’s film by Arriagada, I would have presumed it to be a faithful representation. Now, having read of that response, I can only regard the film as a kind of romantic interpretation of this historic event. That perception changes the semiological nature, the relation of the artistic signs to their contexts of inspiration, entirely.

As significantly, Arriagada’s criticism strikes at the major premise of the film, which argues that political change, in this case, occurs through seduction rather than argumentation or appeal. Larrain’s take on the political process, according to Arriagada, not only misrepresents the facts, but the spirit of the campaign as well.

in “No”

Image: Sony Pictures Classics

Nonetheless, Gael García Bernal does a fine job here playing the young genius. Portraying this devoted father and wounded ex-husband, he conveys a sense of a quiet intelligence at work. A kind of Mozart of the advertising world, a genius in his own, frequently meretricious, medium, he is consumed by its problem and focused on his result.

Regardless of its departure from fact, the film beautifully dramatizes how such unheralded geniuses operate behind the many curtains of the world, and even sometimes, in doing so, make it a better place.

– BADMan

Leave a Reply