Film (2011)

Directed by Errol Morris

Director of Photography: Robert Chappell

Edited by Grant Surmi

Music by John Kusiak

Kendall Square Cinema

Cambridge, MA

This film centers around the story of an abduction which took place in the late 1970s in England. An American Mormon named Kirk Anderson had traveled there to perform missionary obligations. An American woman named Joyce McKinney, with whom he had become briefly involved, followed him. With the help of friends, McKinney whisked Anderson away to a cottage in Dover, chained him to a bed, and had her way with him over the course of several days.

McKinney claimed she was in love with Anderson and wanted to liberate him sexually and psychologically from the clutches of the Mormon Church. From the point of view of the lawyers who contested the subsequent legal case against McKinney, it was a clear matter of kidnapping and manipulation. British tabloids took up the story with a vengeance at the time, and the case, and McKinney, in that context, became famous.

Decades later, McKinney sought to have her favorite dog, a pit bull named Booger, cloned. This event also created something of a journalistic stir, though McKinney, using the first name Bernann rather than Joyce, was not identified immediately with the earlier abduction story.

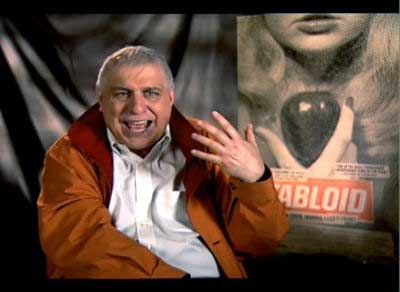

Errol Morris, the noted documentary filmmaker with a taste for the bizarre, had noticed the dog cloning story in the Boston Globe and was drawn further in by the story’s speculation that the Bernann McKinney of the dog case might indeed be the same Joyce McKinney of the earlier abduction case. Morris explored further, found McKinney, and confirmed her role in both stories. Tabloid is the product of his research, and of his extensive interviews with McKinney and with others who were related to the cases directly or through their reporting on it.

Morris is a brilliant interviewer who draws his subjects out in unexpected ways. Through Morris’ choreography of inquiry, McKinney, the ubiquitous star of this narrative, provides a clear and seemingly guileless expression of her point of view about the abduction. Her charm and vividness convey a thoroughly honest and straightforward perspective, setting hefty ballast against the raging storm of lurid tabloid pronouncements about the events in question. Her authenticity is compelling and one is strongly inclined to take her account at face value.

Morris often makes films about offbeat subjects and one might think that he simply indulges a taste for the weird and arcane to garner a special spot in the cinematic pantheon. For example, Gates of Heaven (1981), Morris’ first major success, was a profile of a pet cemetery. Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr. (1999) tracked the career of a man whose calling was to improve electric-chair technologies.

However, if one looks a bit more closely, one sees that there is a philosophical undercurrent running through many of Morris’ treatments which explains his selection of subjects.

Along these interpretive lines, one sees that many of his treatments about the oddball endeavors people get involved with – whether pet cemeteries or electric chairs – are about idiosyncrasies of meaning. In what corners of the world do people find meaning, and what compels them to look for it there? And, especially when the object of meaning is somewhat odd and not conventionally supported by a surrounding social framework, what provides the compulsion to pursue it?

However, works like The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara (2003) treat a somewhat more specific question: how do we reflect on meaning we have constructed at one point in our lives but consider differently at a later point? In this case, what did McNamara, as a principal architect of the Vietnam War, think about his actions in retrospect, years later?

How do we judge McNamara’s fervor in promoting the war in the 1960s against his fervor in repudiating it in the 1990s? The McNamara of the 1990s thinks his interpretations and justifications for the Vietnam War of the 1960s were ill founded. Though his account, in the 1990s, is heartfelt, the subtlety of Morris’ presentation makes one reflect on this kind of drastic variability in perspective. How do we judge this latter-day heartfeltness? What constitutes authenticity in self-reflection?

Consequently, some of Morris’ films move beyond the idosyncratic ways in which people discover meaning to focus more specifically on the question of truth. What is a valid account of a series of events? What is the role of different observers in recounting them? Where, among a variety of perspectives, does a reasonable account, if there is such a thing, lie?

And within this general treatment of truth lie Morris’ more specific reflections about self-deception, what people present to themselves as truthful despite indications to the contrary.

McNamara’s later peace-perspective in The Fog of War suggests an unknowing innocence in the earlier war-promoting perspective. The later McNamara avers that the earlier McNamara could not have known what he was doing, that he was limited and deluded by circumstance. But Morris’ account makes one wonder whether the later McNamara is deceiving himself, telling himself a story about what he did not know earlier. Despite his avowed maturity of perspective, might he be hypnotizing himself into thinking that his earlier actions were a function of ignorance rather than something more dire for which he might be held accountable?

Tabloid brings the issue of self-deception even more to the foreground and plays upon it from several major perspectives. From the first of these perspectives, we see Joyce McKinney – vivid, apparently real, honest and heartfelt – sharing a true account of the story. From another perspective, we see her as completely bonkers, as so immersed in her own retelling of the tale that she avoids telling the truth entirely, and see how she does that expertly. From a more elevated perspective, we look at journalism in relation to the story, and see how it uses its subject as a vehicle for something between reportage and voyeurism. And finally, we look from the perspective of Morris’ film itself, artfully designed as a kind of satire of tabloid pastiche, and raise the question of any film’s management of the relation between perspective, truth, and delivery of entertainment and aesthetic meaning.

Morris is deft and subtle in his amalgamation of the elements, and uses the power of passing detail to shape the contour of an entire story. One might easily believe McKinney’s account wholesale until coming midstream to a note about the ad she placed in a paper looking for help in realizing her 1970s abduction scheme. Contrary to the tenor of McKinney’s account, this ad did not dwell on love but on sexual fantasy. This revelation subtly and resolutely turns the tide of the case’s historic record. It passes quickly but forms one of the pillars of the film’s account of McKinney’s self-deception.

The coda about cloned dogs never invokes the term obsessive but brings it to the fore in a balletic finale. The Fog Of War was also about obsession – about Communism and Vietnam – but one which revealed itself as such, many years later, to McNamara himself. In Tabloid, McKinney’s obsessiveness, never apparent to her, presents itself once again, morphed, in a way that calls to mind Freud’s notion of the return of the repressed, the reappearance of unconscious and never-processed psychological forces. Her leaving the content of earlier obsession unrevealed generated its remanifestation in another form, this time with the poetically-appropriate, obsessively reproduced dogs.

Morris’ interviewing style is spectacular. Though we rarely hear his voice, the openness and availability of McKinney and the other subjects is evidence of his deftness in relaxing and reaching through to them.

Grant Surmi’s editing is appropriately jagged and rhythmic, giving Tabloid a feeling of the punctuated drive behind tabloid publishing, each of its thrusts completely assured and direct, however uncertain of truth it might be.

John Kusiak has provided a wonderful score for the film, creating an overarching sense of dark mysteriousness while, at the same time, embellishing it with a wryness that raises the darkness into the realm of philosophical humor. Kusiak has done the music for a number of Morris’ films and is able, in each one, to capture the combined elements of mystery, oddity, tragedy and irony that form the different compass points of Morris’ outlook. If Morris were considered a kind of American Fellini, Kusiak would be considered his Nino Rota (who composed for so many of Fellini’s classics that one cannot now imagine the works without his music). And Kusiak’s style embodies much of the deftness and charm of Rota’s music as well, embroidering the fanciful gestures of circus-type themes above longing landscapes, weaving melody with atmosphere, whimsy with a penetrating gaze, perfectly supporting Morris’ probing philosophical mission, so expertly dressed in the guise of the arbitrary, the humorous and the fanciful.

Gates of Heaven by Errol Morris

The Fog of War – Eleven Lessons from the life of Robert S. McNamara by Errol Morris

– BADMan

Leave a Reply